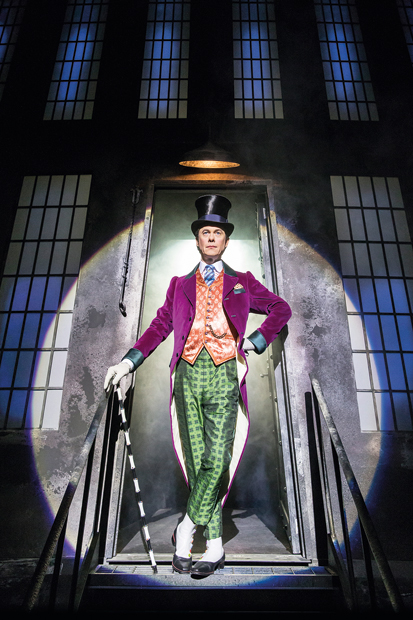

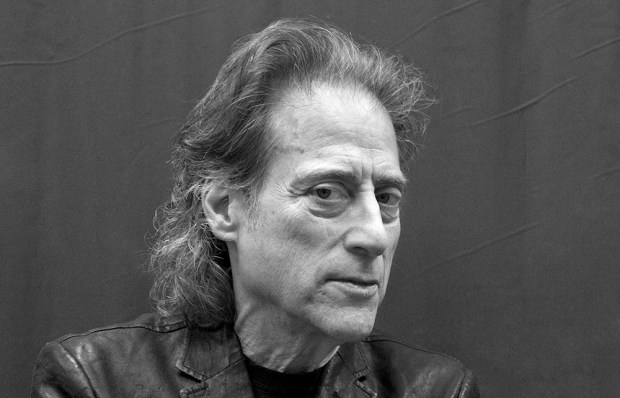

David Haig is one of those actors who can’t escape the visual identity of his characters. He’s the sad suburban salaryman. He’s the pasty-faced petty bureaucrat. He’s the bungling office curmudgeon with a volcanic temper. He just looks that way. Except that he doesn’t. I barely recognise the suntanned Bohemian figure who strolls up and shakes me by the hand. With his summery shirt and his trim grey beard he looks like a rakish Cretan sailor ready to pour himself a double ouzo and start reminiscing about the mermaids.

He’s rehearsing Lear, at the Theatre Royal Bath, when we meet. ‘It’s an addiction,’ he says. ‘Any actor, past a certain age, wants to do it. Everyone approaches it with the same caution and wariness because it’s such a vast and confused play. It’s got magnificent component parts but it very rarely works homogeneously as a whole.’

How is the director Lucy Bailey approaching it? ‘There is an idea,’ he says equivocally. ‘There is a concept. I think it’s a very brilliant one but I’m not going to say much about it. It’s a surprise.’ He then starts to narrow it down for me. ‘It’s not going to be set in the Elizabethan era, or indeed in a mythological British tribal era. I think it’ll be quite immediate.’

‘On a spaceship?’

‘Not a spaceship. Somewhere between the 11th century and the 25th century there is a little decade where we hopefully will locate it.’

He’s keen to bring his experience of parenthood to the role. ‘I’ve got five children and there’s a line, “reason not the need”, which is a quintessentially fatherly line.’ He adopts the tone of needling frustration familiar from his TV roles. ‘Don’t ask me why I want the hall cleared, just do it. Do it for me. “Reason not the need.” On a much bigger metaphysical level that’s sort of what Shakespeare’s saying.’

He got the acting bug early. In a school production of Oedipus he played Jocasta. ‘It was a convincing portrayal at the age of 11,’ he says, ‘in an ankle-length faux-satin gown.’ ‘Who played your son/lover?’ ‘Another 11-year-old boy.’ He scored a hit in a later production of The Critic where he played an ‘immensely pompous’ Mr Puff. A master, whom he keenly disliked, hailed his performance as ‘perfect casting’. He knew early on where his future lay. ‘I was a pathologically lazy child. Acting was the only thing where I would work incredibly hard, far harder than my peers in other fields, and yet I never perceived it as work.’

After school, he went to a kibbutz, ‘as all middle-class hippies did’, and met a Danish girlfriend. He spent two years in Denmark odd-jobbing as a hospital porter, a fibre-glass factory hand, and an apprentice drain-layer. His fluent Danish comes in handy with Scandinavian crime drama. ‘I can watch without subtitles.’

He trained at the London Academy of Music and Drama and developed his technique by working in rep. His stage persona — a brittle and over-emphatic masculine vanity — made him ideal for comic roles. And he regards the sitcom as a seriously undervalued genre. ‘If you think of sitcoms that really hit the target, Fawlty Towers or Blackadder, they seep into the national psyche in a way that a lot of art doesn’t.’ He particularly enjoys the double-think that playing comedy requires. ‘I love that compartmentalising of the mind. On the one hand you’re performing, on the other hand you’re monitoring the flavour of the audience, where they’re laughing, what they’re laughing at, how they’re laughing.’ He has learned to circumvent one of the pitfalls of a lengthy comedy run: the disappearing laugh. ‘Invariably, certain laughs that you think are sure-fire, you lose after four or five months. It’s crucial not to grieve that loss because at the same time you discover something else, and you cherish that instead. It’s taken me 30 years to learn that. I would initially spend hours of pointless endeavour trying to work out how I had lost some crucial big laugh, and how to resuscitate it. Forgetting about it is the best way to resuscitate it.’

He has a parallel career as a playwright but he’s reluctant to reveal details of his latest script. ‘It’s a cool subject and I don’t want anybody to nick it.’ After some prompting he discloses that the setting is Britain, on the eve of D-Day, and that one of the themes is the ‘extremely intense friendship’ that developed between Eisenhower and his army driver, Kay Summersby. Rumours that the pair were sexually involved are hard to substantiate. ‘But it certainly freaked out Mamie [Eisenhower’s wife] back in Washington.’ Summersby was a dashing Irish brunette (born Kathleen Helen MacCarthy-Morragh, in Cork, in 1908), and Eisenhower took her entirely into his confidence. He even insisted that she attend top-level meetings with Churchill. ‘The extraordinary thing,’ says Haig, ‘was that Churchill and FDR condoned the relationship because it soothed and calmed Eisenhower.’ The way Haig tells it, the Allies were being led by a borderline basket-case. ‘Behind his avuncular exterior, Eisenhower was actually deceptively neurotic. He was on about 120 fags a day, his eye was twitching, he had neuralgia, and all that, and yet his exterior being was very calm.’

It’s a cracking idea for a play. The stage version opens next spring in Edinburgh, and Haig has been commissioned to write the screenplay. Understandably, he’s delighted to be involved in so many theatrical activities at once. ‘If you play Gerald Wright in The Wright Way’ (his latest BBC sitcom, written by Ben Elton) ‘and King Lear in the same year, and you’re writing a stage-play set in the second world war, then you’re going to feel happy and fulfilled. Because that’s a range. It’s what I’ve always aimed for.’

He once tried his hand as a director but remains unsure of his skills in that area. ‘If I ever did it again I’d want to be more generous-spirited with receiving ideas. I hadn’t the knack that great directors have: giving the illusion that the performers are working it out for themselves. I don’t think I’d quite got that.’

And what distinguishes bad directors?

‘If the performers feel they’re being tyrannised they will clam up. If an environment of insecurity evolves then that freezes people.’ And you’ve seen it happen? ‘Yes, oh yes,’ he says, nodding gravely. Goodie, goodie. So give us a few names.

‘You must be joking!’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

King Lear is at the Theatre Royal Bath until 10 August.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in