There has been much positive comment about the rehang of the Tate’s permanent collection, which sees a welcome return to the great tradition of the chronological hang and thus gives the visitor a chance to see the development of British art from 1545 to today. At last we are permitted a rest from themed displays and given a proper educational arrangement that maps out our artistic heritage — at least in part. (Most of the larger movements are covered.) This is not a conservative stratagem: there is still plenty of room for discussion and controversy in the various inclusions and omissions (particularly noticeable when we reach the 20th century). But now there is finally on permanent display a backbone or schema on which to build a knowledge and understanding of the nation’s art. We have been in sore need of it, and praise must go to Penelope Curtis, the new director of Tate Britain, for seeing through such a radical re-organisation.

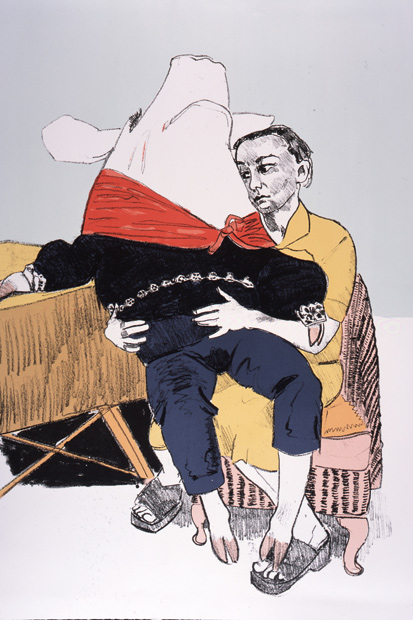

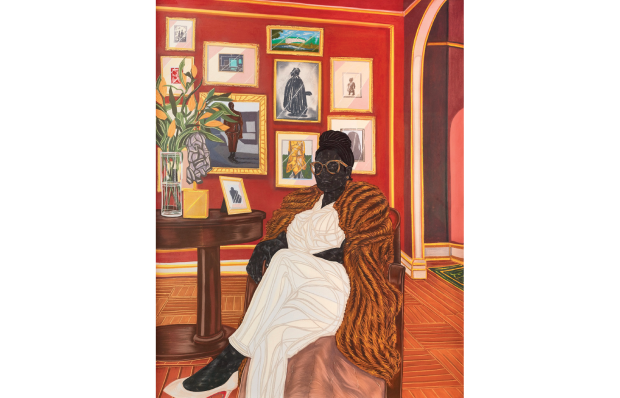

The rehang occupies nearly all of the main galleries on the main floor of the museum with a few rooms off devoted to specialist displays: Henry Moore, Rose Wylie, the witty photographs of Keith Arnatt and so on. If you want to get round the whole thing, allow at least a couple of hours. Ideally, it’s the sort of display worth visiting several times to focus on favourites or those artists new to you. (I guarantee a good sprinkling of these for most people.) But a first visit to gauge the extent and range of work on offer is the best approach. I began by making copious notes, singling out such items as the anonymous ‘Leake Panels’ from the early 16th century, on loan from York Museums (by no means everything on show comes from the Tate’s own collection), religious scenes rather bashed about by the iconoclastic Puritans, or the marvellous Marcus Gheeraerts portrait of Captain Thomas Lee (1594), dressed as an Irish foot soldier with bare legs and open shirt. I also love the Nathaniel Bacon painting of a sexy kitchen maid with a cornucopia of suggestive fruit and veg. There are early landscapes, a grisaille sketch by Rubens for the Banqueting House ceiling and William Dobson’s magnificent portrait of Endymion Porter. I could go on…

If I did go on, this review would deteriorate into just a list of extraordinary paintings (the sculpture doesn’t really get going until the early 20th century), from John Michael Wright to Hogarth, Gainsborough and Reynolds, and on to Wright of Derby, Zoffany and Stubbs. And that doesn’t even take us into the Victorian period. But let me emphasise one of the key aspects of this rehang: the regular strategic interpolation of lesser-known artists. Thus we have George Lambert’s panorama of Box Hill among the Gainsboroughs and Allan Ramsays, or the fabulous (and surprisingly abstract) ‘Peat Burning’ (c.1864–6) by John William Inchbold, in a room of works on paper by the likes of Ruskin. The strictly chronological approach allows us to see how styles and developments overlapped and co-existed; and how startling the modernist works around 1910 must have looked in the context of fading academia.

The 1915 gallery reveals why Gertler’s great anti-war painting ‘Merry-Go-Round’ was not loaned to Crisis of Brilliance at Dulwich (reviewed last week) — it was needed here to make a powerful statement alongside Stanley Spencer and Matthew Smith. Around about, there’s a rare Francis Bacon folding decorative screen from c.1929 (lent from a private collection) that will be surprising to many, together with superb things by Dora Carrington and the underrated James Dickson Innes. Later on we get Hans Feibusch as well as Sam Haile and Ithell Colquhoun: not necessarily well-known figures any of them. But then there is no William Scott, no John Bratby, no Michael Andrews or Craigie Aitchison. Coldstream yes but Uglow no. And where is Allen Jones? Despite these lacunae, the concentrated experience of four and a half centuries of British art made me feel rather proud. Whoever said we haven’t produced any good painting?

Also on the main floor is a monographic exhibition of L.S. Lowry’s paintings which focuses exclusively on his industrial subjects. This is a real mistake. For years Lowry has been out of fashion with the art establishment, dismissed as a bad painter and an irredeemably popular one. The last major Lowry exhibition was at the Royal Academy in 1976, and there won’t be another one for years, so the public has a right to see a proper cross-section of his artistic output. It’s not as if this were the first in a series of shows dealing with different aspects of Lowry’s work. The Tate has put this exhibition on only after much pressure from those of us who recognise his genius: it will not be in a rush to mount a sequel. And one of the reasons the Tate has succumbed to staging a Lowry show at all is because two highly respected modernist Marxist art historians, T.J. Clark and his wife Anne M. Wagner, decided that Lowry would be an excellent vehicle for their particular brand of social history. Hence the industrial focus.

There are many magnificent Lowrys here, and the show is certainly worth seeing for the amount of good original work by this over-reproduced artist brought together in one place at one time. It is, after all, essential to study the surfaces of Lowry’s paintings to appreciate his skill in pushing paint around. He is too often rubbished by those only casually familiar with his work through reproduction. His use of white deserves special attention, for instance. But the formal aspects of his paintings and drawings are of little interest to the present curatorial team. They have a thesis — Lowry as the only great painter of 20th-century British industrial life — and this show is designed to illustrate that.

Well of course Lowry was a great painter of the industrial scene, but he was much more besides. His portraits of people (particularly freaks or eccentrics) are remarkable, and so are his landscapes. His ‘empty’ paintings of the sea and of mountain lakes have rare poetry built into every brushstroke. Yet instead of showing Lowry’s surprising diversity, this exhibition makes a fetish of repeating itself, claiming that for Lowry ‘repetition was a vehicle for thought’. In the end the show doesn’t begin to do Lowry justice, and that is lamentable. Once again curators are given precedence over the subject artist.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in