One of the best articles I ever commissioned as an editor was an account by James Doran of a road trip from the steps of the New York Stock Exchange to the back streets of Detroit in October 2008, at the nadir of the financial crisis. At his destination, Doran found a shocking vista of empty, vandalised factories, all once ‘bit-part players in the now dying auto industry… The desolation was so complete that it hardly seemed real.’ Five years on, the city of Detroit is bankrupt with $18 billion of debts, its population has shrunk to 700,000 from a peak of more than two million, leaving mostly the poor, black and unemployed behind, its public services have disintegrated, and the count of abandoned homes and buildings has risen to 78,000.

Like post-Katrina New Orleans, which I visited last year, Detroit is now being held up as an example of the free-market US economy’s capacity for ‘creative destruction’ and optimism — the belief that something better will always arise from the rubble. But what it really reflects is the opposite of true free markets at work: the highly protected, union-dominated and sclerotically managed nature of the ‘Big Three’ car makers, General Motors, Chrysler and Ford, on which the city’s former prosperity was built.

Saddled with huge burdens of pension and healthcare costs negotiated in better times with the United Auto Workers union, the manufacturers responded by outsourcing as many jobs as possible to China and Mexico. Resting on the laurels of a long post-war boom, they failed decade after decade to design cars that could compete for style with the Germans or for cost with the Japanese and Koreans — resorting instead to the jingoism of Lee Iacocca, Chrysler’s battling 1980s boss, who likened himself to Paul Revere as ‘the only guy on a goddamn horse saying “The Japanese are coming”’ and declared his industry’s problems to be ‘the fault of the dumb sonofabitch who allowed them into our market’. Finally, when bankruptcy threatened Chrysler and GM in 2008 — and the would-be Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney argued for letting them go — the newly elected Barack Obama threw in an $80 billion federal bailout that did plenty for his vote in Michigan and Ohio at re-election time, but little to put the industry on to a sustainable footing against fierce global competition.

If ‘Detroit’ — used as collective shorthand for the Big Three and their hinterland, rather than the physical place — looks like anything over here, it is the ailing British Leyland conglomerate of the 1970s. Since then our own car industry has been reborn out of a combination of foreign-owned factories, better design, high engineering skills and pragmatic union relations — a real-life example of the cycle of creative destruction. Meanwhile, what’s left of ‘Motor City’ itself faces a civic reconstruction that will surely be better severed from the fate of America’s unreconstructed auto makers.

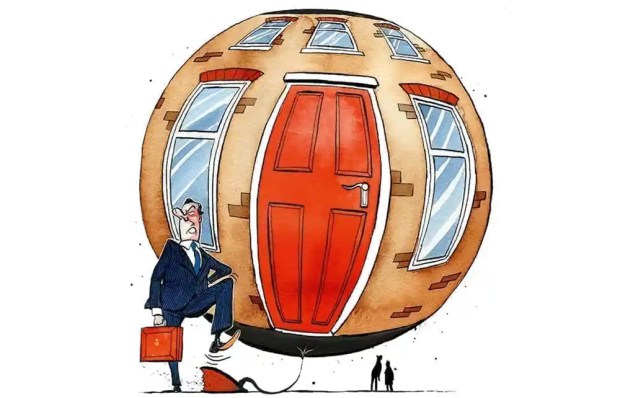

The vultures are circling

The descent of the Co-operative Bank from beacon of banking biodiversity to plaything of political and financial schemers continues apace. Now we hear that two New York ‘vulture funds’, Aurelius Capital Management and Silver Point, have bought a controlling stake in one of the bank’s subordinated debt issues — creating a risk of higher losses for thousands of small bondholders if the vultures behave according to type. ‘We’re not here to cause mischief,’ said their spokesman, but they’re certainly not here to cause joy in a historic institution with a £1.5 billion hole in its balance sheet.

And they’ll stand out like frackers at a Greenpeace rally among a body of investors largely of the British left-liberal urban middle class, who were originally attracted by the Co-op Bank’s ethical policies and mutual parentage. Aurelius is run by Mark Brodsky, a former bankruptcy lawyer who had a hand in the unwinding of Enron. Silver Point is the creation of two former Goldman Sachs men — one of whom, Ed Mule, was a member of Goldmans’ so-called ‘profit enhancement’ committee, focused on cost-cutting in failing companies. Their adviser is an investment bank called Moelis & Co, whose global advisory board is chaired by none other than Lord (Mervyn) Davies of Abersoch. He’s the former Standard Chartered chief who served as trade minister under Gordon Brown; he’s also associated with a New York private equity firm called Corsair, and he’s reported to be lining up an investor group to bid for a chunk of Lloyds — though not the same chunk that Co-op Bank was unwisely lined up to buy before attracting the attention of the vultures. This is all getting a bit complicated: perhaps Mervyn should tell us what he and his American pals are up to.

The Lone Ranger

While we’re on the subject of Americans at home and abroad, my friend Colleen -Graffy, the former spokeswoman for George W. Bush writing in the Wall Street Journal, draws attention to ‘Facta’, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, a measure enacted by the Obama administration that obliges foreign banks to report details of all accounts held in the names of US citizens, on pain of penalties on the banks’ US dealings. Our own government says this could impose extra costs of up to £2 billion a year on British banks alone — and according to Professor Graffy, it will provoke expatriate Americans to consider surrendering their citizenship while making banks the world over reluctant to hold Americans’ accounts, as is indeed already very much the case in Switzerland.

It’s a prime example of the Lone Ranger–style US approach to collecting taxes overseas —involving Department of Justice investigators riding roughshod over foreign governments and institutions, and shunning the kind of multilateral co-operation David Cameron tried to promote at the recent G8 meeting in Northern Ireland. And it’s another way to alienate America’s allies: our friends across the Atlantic should strive a bit harder to understand how others see them.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in