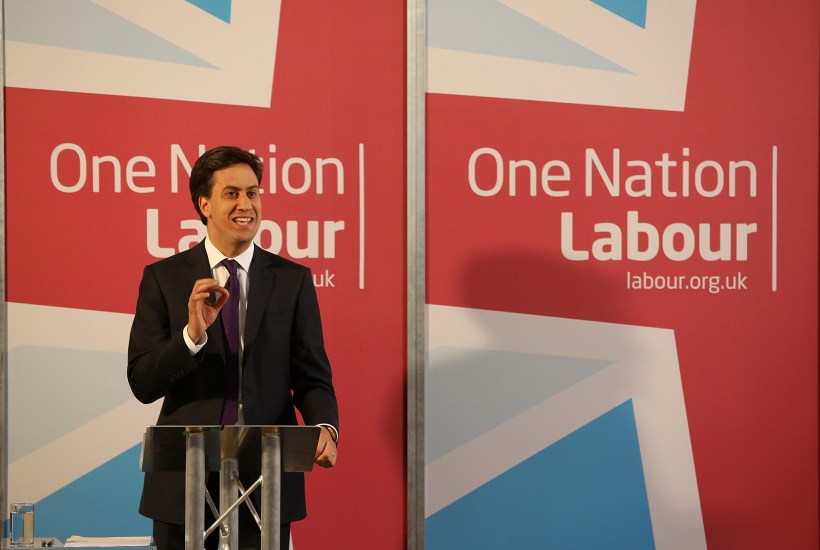

Ed Miliband’s relationship with Len McCluskey was defined in a brief camera shot at the Labour party conference in 2010. After praising trade unions, Miliband added that he would have no patience with ‘waves of irresponsible strikes’. Several rows back, McCluskey, who three days earlier had helped Ed defeat his brother David in the leadership election, was filmed shaking his head and shouting ‘Rubbish!’ Given that McCluskey’s Unite union pays most of Labour’s bills, his word was seen as a veto.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in