Evelyn Waugh once recalled the anguish with which he greeted Edith Sitwell’s announcement that ‘Mr Waugh, you may call me Edith.’ I experienced similar misgivings on the occasion, some years ago, that Lady Violet Powell suggested that I might like to call her ‘Violet’. It was not that Lady Violet — Violet — made the least fuss about her title (‘as unswanky a Lady as could be imagined’, Kingsley Amis once declared); merely that she was the relict of a man whose eye for the social niceties made Lady Catherine de Bourgh look like a bumbling amateur. It was as if George Orwell, knocked into at some Fitzrovian party, had invited you to call him ‘Eric’.

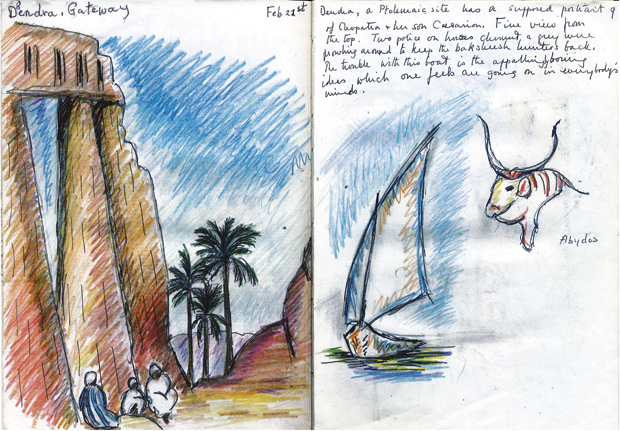

A Stone in the Shade, 15 chapters’ worth of autobiography left unfinished on her death in 2002, takes its title from the vantage point to which Violet would retire, sketchbook in hand, in the course of foreign holidays. It begins in the early 1960s when, with the death of her father-in-law unexpectedly freeing up capital — ‘Now you’ll have to worry about surtax’ was the bank manager’s parting shot — she and her husband Anthony Powell were able to contemplate the idea of overseas travel. By chance Colonel Powell’s obsequies coincided with the arrival of a brochure advertising Swan’s Hellenic Tours. Athens, Beirut, Portugal and Morocco followed in quick succession.

It would be wrong to call these agreeable Mediterranean jaunts — copiously illustrated from the sketchbooks — voyages of discovery, for the Powells take social baggage with them, and the meanest rock on the road to Petra usually conceals a vacationing stockbroker that ‘Tony’ messed with at Eton. ‘It was said in my grandmother’s time that if one sat outside Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo everybody one had ever known would pass by,’ Violet writes at one point.

The Middle East soon reveals itself as Chatsworth en vacances, the Swan courier, watching his charges greet the procession of chums debouching from a New York flight that has just touched down at Heathrow, can only wonder ‘Do you know everyone on that plane?’, and even an obscure village in Delphi turns up a visitors’ book with signatures from Cyril Connolly and Brian Howard.

Tony, meanwhile, is hard at work on The Kindly Ones (1962) — Violet’s favourite among his novels — The Valley of Bones (1964) and The Soldier’s Art (1966), sometimes casting an ironical eye over his Pakenham wife’s vast tribe of Irish connections, but always on hand for a trip to the Pakenham ranch at Tullynally. There is a terrific, if second-hand, account of the funeral of the 4th earl, Edward Longford, in 1962 with a red-faced Brendan Behan reeling drunkenly among the graves, and a picturesque description of a cricket match in aid of the Irish Georgian Society in which the umpires included the be-turbaned 5th earl and Father Martin D’Arcy, the celebrated Jesuit fixer, dressed in cloak and top-hat. Tony, alas, having last taken to the field half a century before, ‘had no wish to reconnect himself’ and presumably skulked beyond the boundary ropes.

In her sympathetic introduction, Antonia Fraser notes her aunt’s appeal to ‘future literary biographers’. Certainly A Stone in the Shade is full of sharp, reminiscing glances — Cyril Connolly prowling the pavements of Cadogan Square beneath his ladylove’s window, a ‘distinctly tottery’ Evelyn Waugh staying the night at the Powells’ house in Somerset — but its real interest lies in the sensibility that runs beneath. She can be very funny — see her account of dancing the twist — but her memories of family tragedy have an unusually delicate touch. A modern autobiographer would have gone to town on the ten-month period in 1915 when there seemed an outside chance that her father was still alive in a POW camp. Violet notes only that it ‘established an embarrassment among his children which his wife’s emotional inhibitions were powerless to disperse’.

The choicest compliment of Anthony Powell’s famously laconic memoirs is that such-and-such a contemporary was ‘rather a great man’. Violet Powell, in her own unassuming way, was rather a great woman.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

D.J. Taylor has written The Novel in England Since 1940 and Bright Young People.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in