Revolution shook Mexico between 1910 and 1920, but radical political change was not mirrored in the art of the period. In this exhibition, we do not see avant-garde extremes, but witness instead a deepening humanism, as if for once art was interlocking with human need. The cultural renaissance that followed was state-sponsored, and artists were employed by the Ministry of Education to promote the revolution. This was political art at its best, and three artists were active at its heart: los tres grandes, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Their most significant achievements were murals, which remain firmly in place on Mexican buildings and thus are difficult to make an exhibition about. This problem has been solved by having a token representation of Mexican art, lots of photographs, and some fine paintings by foreign visitors who were inspired by Mexico.

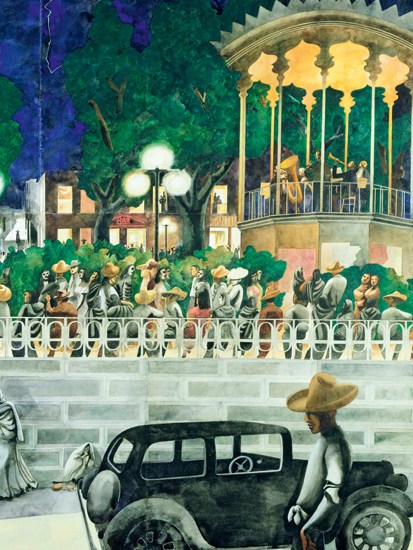

It’s an intelligent solution and the exhibition is more enjoyable than expected, if somewhat sparsely hung. The first room sets the revolutionary scene with mostly documentary material and some of the remarkable prints of José Guadalupe Posada, an influential satirical illustrator still highly regarded today. In Room 2 the visitor is greeted by a powerful and rather beautiful Rivera oil painting, entitled ‘Dance in Tehuantepec’ (1928), the single example of his work in the show. (Orozco and Siqueiros are similarly represented.) The end wall is given over to photographs by Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, both compellingly brilliant and here nicely contrasted. For example, photos of the inside of a circus tent by both are juxtaposed, while Weston offers a beautiful cloud study and Modotti a shot of telegraph poles like Aztec sculpture. Further down the room are paintings of rabbit-faced Mayan women by Roberto Montenegro and the legendary Zapata (by Siqueiros) with his boomerang moustache.

On the opposite wall is a group of oils and watercolours by the underrated English artist Leon Underwood (1890–1975), better known as a sculptor, but interesting in all his endeavours. Underwood visited Mexico in 1927–8 and was much influenced by what he saw, which continued to feed into his art for a decade. In the third room is the Orozco, a thrusting action painting built on the diagonal. More intriguing are the pair of semi-abstracted Marsden Hartley landscapes (when will someone put on a show of this little-known and highly original painter?). There are lots more photos, the best being by Cartier-Bresson of prostitutes, Paul Strand of village buildings, and Laura Gilpin of the Mayan site of Chichen Itza. On the end wall are a couple of monumental Edward Burra watercolours — what a painter he was — and the exhibition finishes quietly in the last room with political photos by Robert Capa and rigorously abstract paintings by Josef Albers, a keen visitor to Mexico. A tiny self-portrait by Frida Kahlo is a bonne bouche on the way out.

We talk of someone having a bent for satire. I don’t think of Ralph Steadman’s line as bent or twisted, but scorching and excoriating, jaggedly looping and relentlessly searching. We might as well say Steadman has a circle for satire — an endless circle: the snake biting its tail, or the nought of nul points for a politician’s probity, or the orchidaceous orbicularity of ‘it’s all balls’. Or we may talk of a zigzag for satire, a lightning strike from the heavens skewering our manifest faults and foibles. However we look at it, Steadman doesn’t just take his line for a walk, he hoicks it up on a rollercoaster ride round the corruptions of the human heart. He’s driven, is Ralph, and he drives our eyes like a stock-car racer or the midnight express, with plenty of fuel-injection outrage and only the lightest touch on the brakes. He’s a runner of moonshine to the soul, subversive extraordinaire, general inspector of the Augean stables. (And it’s a mucky job.) A deep-dyed Romantic, he attacks whatever dishonesty and wickedness he sees around him because he feels it personally in every atom of his being. He also celebrates, where celebration is due, with a lightness and wit that offset his piercing satirical probing.

Steadman is an artist rather than a mere caricaturist or cartoonist, because his vision penetrates deeper and resonates more widely than the ephemeral joke. It aims at the timeless in its human relevance, and deserves to be accorded the same degree of attention as more self-consciously ‘serious’ art. But because Steadman is primarily known as a cartoonist, there is none of his work in our great national museums, and this retrospective has to be staged at the Cartoon Museum. But it should at once be said that the Cartoon Museum has done a brilliant job in mounting this show, although its premises are not especially spacious and inevitably the extent of the exhibition is restricted. (For those who cannot get to London, it will be travelling to The Art Works in Halifax, October to December. And there’s an excellent large-format paperback catalogue, priced £14.99, packed with images and elucidating text, from the likes of Will Self and Martin Rowson.)

Steadman draws on large sheets of paper using dip pens and India ink, frequently bodied out with collage, acrylic paint and coloured inks, sometimes applied with an atomiser spray or an old toothbrush for random splatter. He began in black and white, drawing with acuity but more gentleness than in his mature style. He worked for Private Eye, and his hilarious ‘New London Cries’ from the mid-1960s have something in common with Monty Python. What he could do with colour can be seen in his late-60s Francis Bacon spoof and his later book illustrations — to ‘The Big I Am’ or ‘I, Leonardo’. His black-and-white illustrations reach a pastoral (if slightly hallucinogenic) peak with the Alice books, but Steadman always attributes his 1970 meeting with the Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson as a stylistic turning point in his career. After that his line has more bite.

‘He’s an absolute genius, I hadn’t realised how good he is,’ was one overheard comment from a satisfied visitor. I could have wished the exhibition thrice as big, but it nevertheless gives a real flavour of Steadman’s uncommon achievement. Hunter Thompson wrote: ‘His view of reality is not entirely normal. Ralph sees through the glass very darkly.’ Well, he should know. But the white of the page generally spreads light on this darkness, and humour keeps breaking through to save us. We need this great enemy of pretension and roguery: long may he draw us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in