On board the Weatherbird off the Peloponnese

The old girl groans and creaks as we tack time and again, the breeze right on the nose as we negotiate the turquoise coastline. She’s gaff-rigged and good upwind, the only annoyance being the ubiquitous speedboats driven by fat Greeks who come by for a look-see. From my porthole, I see only green pines and olive trees with the light blue of sky and sea as background. My maternal house near Sparta is now a museum, the main square named after my grandfather, who is among the very few public figures not to have robbed the place blind.

Greek hacks are among the most illiterate in an illiterate profession, having mistaken me for another whose name sounds like mine, but one who doesn’t dress at Anderson & Sheppard and whose last mistress resembled ‘la tricoteuse’. This poor slob was accused of being a Nazi Holocaust-denier by lefty rags after what I wrote in these pages two weeks ago. A man by the name of Alexis Tsipras, leader of the main opposition party and referred to by everyone as the next prime minister, went on record calling me a Nazi racist, or rather the other poor slob he mistook as yours truly. It was all great stuff. And indicative of what journalism and politics are like in the birthplace of selective democracy. Blame the wrong guy, and once caught out use words such as the Holocaust, racism, Nazi and Fascist to make up for the gaffe. In the meantime, I’m cruising and having the time of my life. My annual birthday party went off fine, the Greek royal family honouring me with their presence along with some very, very good friends. The less said about the hangover the next morning the better.

Weatherbird is full of ghosts. The first night the mother of my children as well as my boy saw a tiny figure in white walking through the cabins below decks. I didn’t believe them until I saw my five-year-old granddaughter sleepwalking in her little white dress — at least I thought it was her. Real ghosts or not, Gerald Murphy’s presence is everywhere, and he remains as in life a Candide-like figure in that his soul remains pure. As is the trap of the ‘good life’: fame, fortune and beautiful women. There are essays and essays on the Murphys on board, some of them touching on the ‘dark’ side of their glamorous life. Notes on the correspondence between Papa Hemingway and Gerald Murphy concerning the former’s marriage to Hadley and his leaving her for Pauline show Papa’s suspicious and quick-to-condemn nature. Gerald had praised Papa and Hadley’s union while in Pamplona, ‘You two children grace the earth,’ but after Papa’s first success with Fiesta and abandonment of Hadley, Gerald’s letters to him included ‘Act sharply and clearly’, and hinted that Hadley had become ‘miscast’ in the role as guardian of Papa’s talent. Hemingway thought Gerald had gone too far in his assumptions about his personal life, and decided Murphy was a dandy who could not be trusted.

Even worse, Papa then started to write to Sara Murphy ambivalent love letters — was it real friendship or pure lust? — hinting at Gerald’s ambivalent sexuality. However much I hero-worship Papa, this pissed me off. Gerald was not homosexual, but had suggested in letters to Archibald MacLeish and to his own wife that there was a ‘weakness’ in his sexuality. ‘I am not into savage sex…’ In other words, unlike Mussolini, he wouldn’t grab a woman, shove her up against a wall and ravish her standing up. Although not an expert, I don’t think an inability to screw a woman against a wall makes one a homo. Gerald had defined tragedy as a fear of life — and Papa pounced on that definition in one of his letters to Sara. But Sara didn’t bite. (Unlike the 6ft sailfish we caught just off Kyparissi, hauled on deck and mercifully killed by the crew instantly. We dined on it that evening.)

My interpretation of Gerald’s letters and his fears were not those of Papa, but those of an artist. The impersonal precision with which he depicted a watch, an engine room or the smokestack of a liner shocked even the modernists of the time. Gerald, like Scott Fitzgerald, was evoking the past with a resonance of the new and mechanical. The cult of the machine was very American and it fitted Gerald perfectly. His canvasses were large, almost billboard-like. Only four remain, which is a real tragedy.

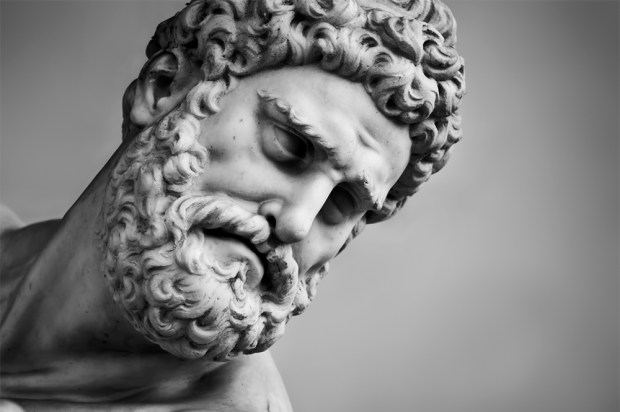

But back to the present. Someone on board said that there was no unhappy love before people had sex. It sounded profound but actually it was just a thrown-up remark with no meaning. I said the real tragedy of Greece is that no one ever learns anything from the past. Journalism is as yellow as before, just as corrupt as before, and just as inaccurate. We wallow in lies, as the Arabs do, but unlike them we call ourselves Europeans. We are nothing of the kind. The only thing we inherited from the ancient ones are jealousy and envy. We have no Pericles, no Miltiades, no Themistocles, but plenty of Alcibiadeses. We lie and lie in order to cover up our lies, but then we write that we are like our ancestors, which is the greatest lie of all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in