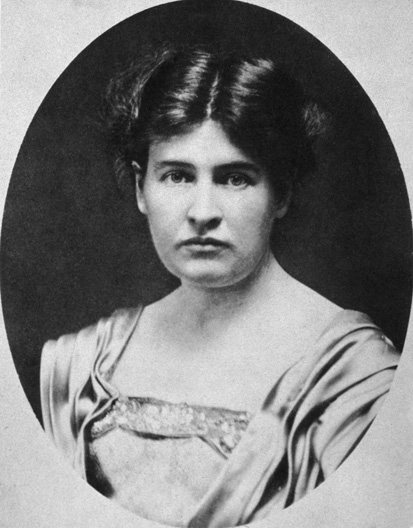

Willa Cather is an American novelist without name-recognition in Europe, yet she had a wider range of subject and deeper penetration of character than other compatriot novelist of her century. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Bellow and Roth vie with, but never beat, her emotional force and the beauty of her prose. The great obstacle is that she is a woman, with a name that sounds silly. She knew more about survival in extreme conditions than other novelists, she wrote in 1913, ‘but I could never make anybody believe it, because I wear skirts and don’t shave’.

As a young woman, Cather feasted on Virgil and Shakespeare — and it shows. In O Pioneers! (1913) and My Ántonia (1918) she celebrated heroic young women struggling for fulfilment, and proving their powers of leadership, on brutal, impoverished homesteads in 19th-century Nebraska. The Song of the Lark (1915) depicts the fierce, ruthless concentration required by artistic ambition. Her flawed but powerful novel on the first world war, One of Ours (1922), would have been hailed if it had been written by a man. A Lost Lady (1923) is a miniature masterpiece: Madame Bovary set in a philistine town called Sweet Water — and my favourite of all her work. Her historical novels, Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927) and Shadows on the Rock (1931), are set in New Mexico and Quebec. In all her books, the evocations of American landscape are sumptuous.

The imaginative sympathy that devised her characters, like the passion with which she made them live, is prodigious. Her short story ‘Paul’s Case’ conjures the cravings, snobberies and fantasies of an epicene lower-middle-class youth: it is astonishing for the date of its publication (1905). Arguably she and George Eliot are the only non-Jewish Anglophone writers who have created rounded Jewish characters.

After Cather’s death in 1947, her executors fulfilled her wishes by prohibiting film adaptations of her books and publication of or quotation from her letters. With the recent lifting of this interdiction, Andrew Jewell and Janis Stout, who have long cherished her memory, prove themselves to be the most considerate of epistolary editors. Their book is hugely informative for anyone who already cares for Cather’s work; it will be an appetiser for anyone who has not read her; it is a steadier guide to her character and conduct than any existing biography; and it provides a beguiling picture of Cather — a romantic, a disillusioned American, a sophisticated creative intelligence with oddly artless reactions, a semi-recluse capable of gregarious affections.

She grew up on her family’s ranch at Red Cloud, Nebraska, near the Kansas state line. It was a bleak, almost treeless expanse, where droughts drove farming neighbours to bankruptcy, insanity and suicide. She was a tomboy who, when young, took a male alias. She had an intense, lifelong devotion to two of her brothers, but squabbled with sisters who feared her physical toughness and dominant imagination, and envied her successes.

There are suppressed Sapphic thrills in the early letters: ‘I was in rapture because I had accidentally touched her hand’, she wrote of one girl. She also described driving 20 miles by horse buggy to attend a dance in Blue Hill, Nebraska:

I found a dandy sort of girl, handsome as a picture and finely educated … she was so glad to meet somebody ‘from civilisation’ that we talked books and theatre until the daylight came through the shutters.

Who can know if it is artless simplicity or arch double entendre when she writes, aged 19:

I am pretty well now, save for sundry bruises received in driving a certain fair maid over the country with one, sometimes indeed with no, hand at all. But she did not seem to mind my method of driving, even when we went off banks and over haystacks, and as for me — I drive with one hand all night in my sleep.

Cather was a pioneering career woman who in the late 1890s supported herself as a magazine editor and then as newseditor at the Pittsburgh Leader — an unprecedented post for a woman. She was later a successful managing director of McClure’s Magazine. With her gumption and vitality, she was a stalwart among women facing the ‘rough-and-tumble’ of competitive work. It is regrettable that her book Office Wives — a collection of stories about women in business — was never completed.

She believed in the ennobling effects of suffering. ‘What a beautiful, noble, sad — and humorous — face she had,’ she wrote in a letter describing a woman whose two sons ‘had just had their eyes blown out, dynamiting orchards’. She believed her fellow Americans overrated ‘the pursuit of happiness’ in life: ‘The pursuit of pain seems to be just as ineradicable a human instinct.’

Although Cather heard no music until the age of 16, she later developed a reverent love of music-makers. In her early naïveté she extolled Ethelbert Nevin, best known for his tune ‘Little Boy Blue’, as ‘the greatest of American composers’. He had ‘the face of a boy and the laugh of a girl’, resembled ‘a shepherd lad strayed out of Arcady into this dreary land of dullness and shop-keeper standards’ and ‘used sometimes to seem like a man stripped of his skin, with every nerve quivering’. In her discriminating maturity she met the Menuhin musical prodigies in Paris, and adored them. ‘For 16 years,’ she wrote shortly before her death, ‘the Menuhin children have been one of the chief interests and joys of my life.’ She cherished their gifts, but supremely loved their vivacity and serene wisdom. She wrote of her beloved Yehudi: ‘He sees the souls of people — that is his peculiar gift.’

Overall, Cather’s capacity for hero-worship is endearing. She adulated A.E. Housman, and burst into tears of disappointment after meeting him. She was as gleeful as a child after spending half an hour in Albuquerque with Rin-Tin-Tin. Depressed by the war in 1942, she jollied herself with a make-believe game in which Winston Churchill joined her for afternoon tea:

I don’t think there is anybody on earth who knows better how to get every possible pleasure out of every single day, from his first egg at breakfast to his last highball at night. I find that an imaginary tea with him, meditating on his unfailing buoyancy, does me a great deal of good.

One cannot read these letters without succumbing to this brave, original, brilliant woman who never forgot, as she says in one letter, ‘it’s the heat under the simple words that counts’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Richard Davenport-Hines, is the author, most recently, of An English Affair, about the Profumo scandal.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in