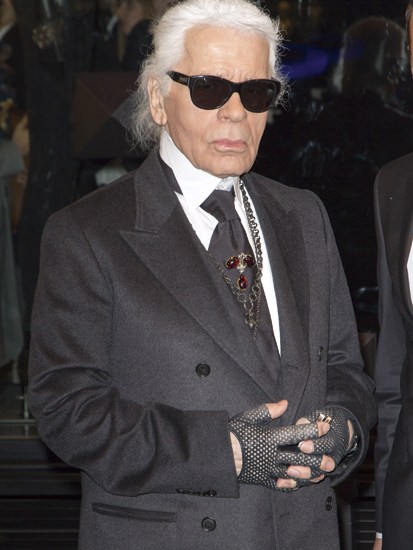

Every fashion era has its monster and in ours it’s Karl Lagerfeld, a man who has so emptied himself on to the outside that there is no longer any membrane between what he is, what he does and what he looks like: a macabre dandy for the electronic age, a Zen businessman as effective as Andy Warhol or Michael Jackson or David Bowie in propagating product and persona as one. ‘I enjoy the luxury of being at the centre of this complete universe that’s mine,’ he says with the concentrated generosity of a narcissist who wants to thrill the whole world in order to make it his pool. The eternal dark glasses might suggest otherwise — that here is someone with a concealed inner life — but he affects to deny it (‘With me there’s nothing below the surface, but it’s quite a surface’), so presumably the dark glasses are just for the pool’s reflected glare.

His outrageously unattractive appearance is both a precipitation of temperament and a promotional tool for the collections he designs for Chanel. This media costume became fixed a long time ago into that of a sado-masochistic ghoul out of the Brothers Grimm, re-imagined by an Expressionist cinéaste: ‘I like the idea of craziness with discipline.’ To top it off he wears — the nerve of the man — that pendant of ultimate awfulness, a grey ponytail (‘You have to do things one is not supposed to do’). For Paris’s most successful couturier to come up with a personal image so tasteless and brittle is an unusual kind of bravura, rendering him uniquely recognisable, even in silhouette.

It is also armour of course. Lagerfeld sounds phobic — ‘I don’t like being watched at all’ — and you’d expect him to remain silent, for fear of exposure; after all, Warhol confined himself to ‘Oh really’, Bowie rarely speaks off-the-cuff and Michael Jackson whispered coyly at the earth. But it turns out that Lagerfeld has a mercurial, sometimes devastating way with words. I first became aware of it in Rodolphe Marconi’s documentary-film of 2007, Lagerfeld Confidential. Years ago I was offered an interview with Lagerfeld and turned it down for intellectually snobbish reasons. I hugely regretted that, after seeing the film; for in it Lagerfeld’s mental agility was exceptional and very entertaining, especially his knack of recasting an accusation and throwing it back as a small glittering ball. He was also revealed as a passionate reader and collector of books.

The World According to Karl attempts to capture something of his rippling mind but is less successful than was the film. Lagerfeld’s tongue works best in action; deprived of context and intonation, the bounce is lost. Also the editors don’t have enough of these remarks, and they have to be stretched to make a volume which has become a design object in black, cream and white with many unplanted spaces. Yet something of Lagerfeld’s surprising essence may be found here. Aphoristic philosophy is a German speciality, developed by Lichtenberg and Nietzsche, and it’s merry to see Hamburg-born Lagerfeld as their unlikeliest offshoot.

He says ‘I never fall in love’ and ‘I’ve gone beyond ego,’ laying claim to the dandy’s nihilism which confers a cruel freedom of operation. He embodies a very contemporary form of success, empirical but ruthless: ‘When people think it’s all forgotten I pull the chair away — maybe ten years later.’ He is an ascetic with a dash of the surreal: ‘I want to be chic coat-hanger.’ He works hard, but life is a game, and unfair too: ‘Luxury is freedom of spirit . . . I can say what I want because I’m a free European.’ Much of the content is terribly self-referential (‘I never drink anything hot’), but his elliptical self-mockery is also on show: ‘I don’t mind being a monster, but there are limits.’

As Tennessee Williams wrote in Sweet Bird of Youth, ‘Monsters don’t die early; they hang on long. Awfully long.’ But Karl has an answer even for that: ‘Everyone knows I’m 100 years old — so it doesn’t matter.’ In fact he’s 80, so must be sitting on a ton of experience. But alas:

I will never write my memoirs. Because I have nothing to say . . . I don’t remember anything. My trick is to burn everything and start again from zero . . . I’m a professional killer . . . My life is science-fiction.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in