Since trial by jury is so expensive, government is keen to cut costs on legal aid by ‘alternative dispute resolutions’ (ADR) and settle e.g. family disputes before they ever come to court.

The situation in classical Athens was similar. Though jurors were paid by the day, enabling money to be saved by cramming in as many trials as possible in the session, their numbers were very high — 201, 401 or 501 depending on the case in hand — and the cost consequently heavy. So the authorities did all they could to engineer an early settlement.

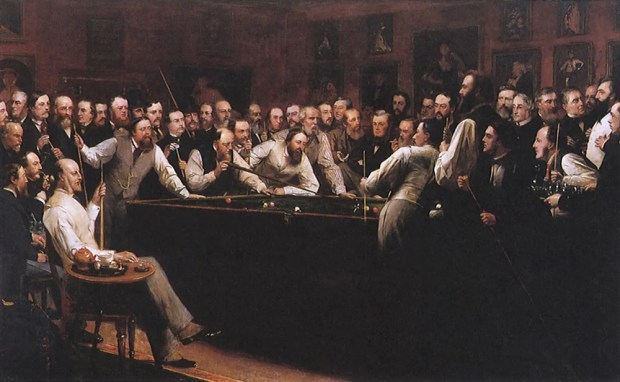

The process was part mediation (persuading both sides to agree a settlement) and part arbitration (a settlement imposed by a third party). Step one would be for the two parties to a dispute to appoint a private citizen to settle it. We have an example from a comedy by Menander (4th century bc), in which A has found an abandoned baby, gives it to B to rear, but wants to keep the necklace which the baby had with it. B objects, so they ask a passing stranger C to mediate, agreeing to be bound by his decision. C decides in favour of B. A grumbles but complies.

If that did not work, the dispute went to public arbitration. The litigants were under oath, and the arbitrator a citizen over 60, against whom a litigant could bring a case if he thought the verdict corrupt. But his verdict was not binding, and the litigants could opt for jury trial, if they so chose. In that case, the evidence which they had produced before the arbitrator was sealed up in a clay jar called an ekhinos (‘hedgehog’!) and could not be added to.

The purpose of this is not clear: was it to ensure both sides knew what they would be arguing about at the trial? To make them take arbitration seriously, knowing it was their final throw before a trial? Or to protect the arbitrator, after the event, from being confronted with evidence he had never seen?

Athenians would also approve of swearing to tell the truth on the Bible (recently challenged), because an oath made the god an overseer of the contract and guarantor of one’s word. He or she would feel insulted if it was subsequently broken.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in