Dinner by Heston Blumenthal, a brown cavern in the Mandarin Oriental hotel, Knightsbridge, has won a second Michelin star. These stars are food ‘Oscars’ (Hollywood has eaten everything, despite its tendency to despise food) and ensure that wealthy Americans make a detour to dine beneath the stars. This new elevation means that Blumenthal, at least technically, is Britain’s finest cook; the Meryl Streep of dripping and sweat.

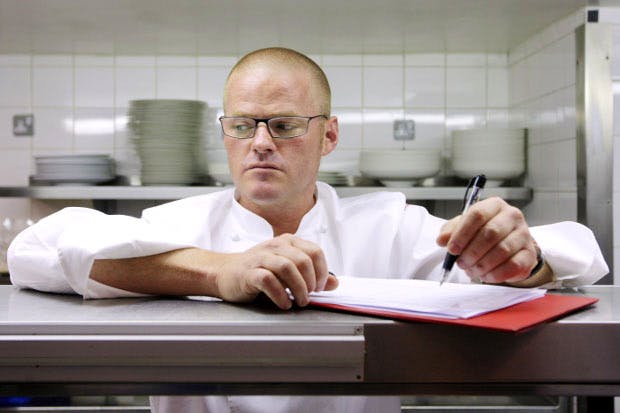

Blumenthal is a historian chef, a successor to the celebrity chef; he is an intellectual. I say this not because he wears spectacles but because his website has a dictionary definition of dinner — ‘A formal evening meal, typically one in honour of a person or event — from old French Disner’. Blumenthal doesn’t cook food — he regards it, divines it, and rips it apart — and his devotees have fanned out, and spend their days designing salad in the shape of the elves of Rivendell, and vegetables in the shape of hurt. On eating a seafood dish at the Fat Duck, for instance, diners are invited to listen to the sea via iPod, an experience so synthetic I suspect it isn’t worth the trouble, and I’d get a train to Penzance and suck on a raw mackerel instead. (I hate an homage.) I wouldn’t mind Blumenthal’s molecular gastronomy so much if it didn’t remind me of both the idiocies of Paris couture and Alain de Botton. But it means that any meal at a Blumenthal joint carries almost unbearable expectations, for the diner and the food. Poor food.

If Dinner is a library of British cuisine, it looks oddly like Harveys the Furniture Store. Blumenthal may seek beauty and truth in food but he hasn’t got a clue about dining tables; the truth is, Dinner is irredeemably brown, brown as far as the eye can see, a prostrate homage to brown, in brown. The lights are translucent plastic jelly moulds and the cushions are a beady orange; it’s an ugly restaurant in an ugly hotel, and very masculine. This makes sense for the customers, an unceasing parade of youthful Scrooge McDucks, looking for meaning in their wallets. Why did they break their hearts to make money? So they could have lunch in Dinner, of course. This restaurant is a question in search of an answer; it is nearly, in psychological terms, a yacht. None of this is Blumenthal’s fault; he does his bit for normal folk by designing ready meals for Waitrose, and he once attempted to rescue Little Chef by making it serve coq au vin. But he is a man, like Rick Stein with his Magic Steineyworld in Padstow, for whom food, and therefore the earth he walks on, is not enough. No one can co-write a paper ‘Differences in Glutamic Acid and 5’-Ribonucleotide Contents between Flesh and Pulp of Tomatoes and the Relationship with Umami Taste’ and be content. Even so, he is very grand now; he has a coat of arms, featuring a portion of duck. One day, like the restaurant in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, he will engineer a cow that wants to be eaten, even if, as I suspect, he sits at home sucking on McCain’s Oven Chips and Alphabetti Spaghetti.

So what lies here, in the land beyond food? My Broth of Lamb (c. 1730) was cool and slightly slimy; my companion’s snails were small and surrendered, with no promise of resurrection. She adored her sea-bass, and said it tasted ‘weird’, but my Hereford Ribeye (c. 1830 — really?) was over-seasoned and tough; I can always finish a steak but not one with a degree. Tipsy Cake (c. 1810), a glorious squelch of pineapple, was a marvel, but by the time we had ordered green tea at £14 a head, I was too annoyed to order the house special, ice cream frozen at your table, in the shape of your regrets.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in