One man’s lonely, friendless trudge down the mean streets of Manhattan. One woman’s loved up festival of adoration at the Sydney Opera House. Are these to be the last snaps on the final page of the Rudd and Gillard governments’ family photograph album, the ones that set their respective images for ever?

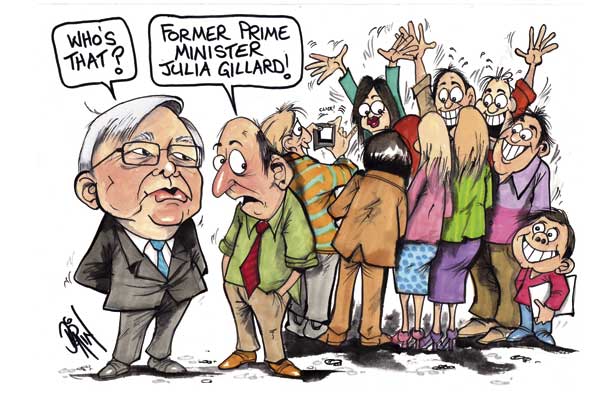

History — at least of the first draft variety — is recasting what until just days ago seemed the verities of Labor’s recent revolving-door prime ministers. Kevin Rudd was supposed to be popular, a brilliant campaigner and the Labor party’s saviour. Julia Gillard was supposed to be hated, wooden and the single-handed destroyer of Labor’s primary vote.

Suddenly there’s a reversal. Rudd is the unpopular dud campaigner who dragged Labor’s primary vote down to its lowest level since the early 1930s. Gillard is the adored, charming Opera House interviewee who looks like she could well have fronted a winning campaign. What the hell happened, and will it stick?

Last year a long-time journalist with direct, close experience of Rudd buttonholed one of his key advisers (think balding, moustachioed) and pressed him on why he was working so hard to get Rudd up when he had to know he was a flake. Don’t worry, came the response — we only have to hold him together for five weeks. The length of a federal election campaign was the implication. The journalist was shocked at the extreme cynicism of it. The balding, moustachioed adviser probably got a shock of his own, as did other Rudd backers, when Rudd failed to capitalise on his restoration and call a snap election — his best chance of leading Labor to victory in 2013.

And for a moment there, when Rudd won the June leadership ballot, there was a small but real chance that he could. His smile had not yet cracked, his shtick had not yet palled, his policy incoherence had not yet manifested in glorious missteps like the Northern Territory special economic zone and moving the navy to Brisvegas. But instead of calling the election immediately as anyone who was anyone in the ALP urged him to do, he dithered. He hung about. He did some more photo opps. He went to Afghanistan. He’d do anything — anything but go to the people and risk his hold on the ‘C1’ number plate he’d only just got back.

When it comes to election timing, Rudd’s got the moves of a ballroom dancer with two right feet. This was the second time he’d foiled possible victory for Labor, the previous being 2010 when colleagues universally urged him to call a February election in the wake of the failure of the Copenhagen climate change talks. He dragged his heels then and a few months later lost the leadership. He dragged his heels this time and lost the election.

Yet paradoxically, time is on Rudd’s side. Despite his unparalleled treachery towards a serving Labor prime minister, he hasn’t been expelled from the ALP, he still has a seat in parliament and he’s a relatively young man. He could hang around like Billy Hughes who served 51 years and seven months in the House of Representatives before being carried out in a box at 90 years old. Rudd will be 90 in 2047. Don’t think age would pose a barrier to his ambition. Billy Hughes was leader of the United Australia party at the age of 78 and Rudd is capable of being as wily, ambitious and resilient as Hughes at the same age. When you’re playing a long game like Rudd, the chances to relaunch and remake yourself are endless. There’s always some young ’uns among the ranks of incoming MPs each election to flatter and groom to his corner in caucus. There’s always another journalist to put on the information drip in exchange for favourable coverage. Rudd’s history is still in the making. No Labor leader is safe while he remains in caucus.

For Gillard, however, the political years are over. The opportunity for historical rewrites is now. The two ‘in conversations’ with Anne Summers at the Sydney Opera House, and later at the Melbourne Town Hall, have been smashing successes in connecting her with the supporters — mostly women and girls — always there but subsumed by the sturm und drang of the last three years of Australian federal politics.

Gillard is drawing a Whitlamesque mantle upon herself, and the parallels are apposite. Like Whitlam she presided over a troubled government that nevertheless racked up some signal progressive reforms. While their respective demises were at different hands, like Whitlam she was unceremoniously tipped out of the prime ministership and showed considerable class in defeat. Labor loves a heroic loser and Gillard is emerging as a hero to that great slab of the party mostly ignored and trampled on by the angry, headbutting brothers and male comrades: women.

There is some irony about this, given Gillard’s less than feminist solidarity with other caucus women during her rise: she would be nice to them only after she’d crunched them and they fell into line. A contemporary feminist icon she has become nevertheless and, after surviving the onslaught she did in office, no woman would begrudge her claim now to feminist stripes. Mostly we’re just thrilled she didn’t crack. That would have really set us back.

As for the verdict of History with a capital ‘H’, it will come a lot faster for Gillard than for Rudd, who hasn’t had the decency to leave the building. Some people just never know when it really is time to go.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Chris Wallace is a Canberra writer. She has written books on Don Bradman, Germaine Greer and John Hewson.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in