Emilio Greco (1913–95) is considered to be one of Italy’s most important modern sculptors, and certainly he was a successful one, enjoying considerable popularity and renown with his deliberately mannered re-interpretations of classical subjects. A figurative sculptor, Greco went in for elongated limbs and awkward yet dynamic poses that often have a surprising elegance and no little wit. His most celebrated work is ‘Monument to Pinocchio’ (1953) in the Tuscan hill town of Collodi, and one of the highlights of this new exhibition at the Estorick — no doubt intended to revive Greco’s reputation (on the wane since the 1970s) — is a bronze study for it.

Emilio Greco: Study for the Monument to Pinnochio, 1953 and Dress the Nude (fragment from the Doors of Orvieto Cathedral), 1962

Emilio Greco: Study for the Monument to Pinnochio, 1953 and Dress the Nude (fragment from the Doors of Orvieto Cathedral), 1962

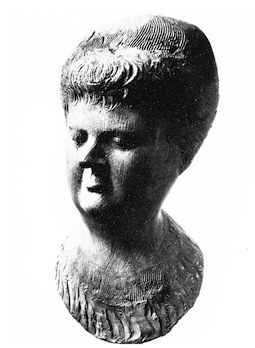

For this centenary exhibition, the two downstairs galleries have been filled with some 40 works by Greco, mostly sculptures and drawings of women. The early work is undeniably the best: a fact made inescapable by the merest glance at the heavily cross-hatched ink drawings from later years. There are a number of these around the walls, and although their style is by turns robust and polished, the subjects are sentimental and verging on soft porn. Greco had found a profitable formula and he stuck to it. But in the earlier part of his career he looked more to Etruscan, Greek and Roman art and made some of the most memorable and rewarding of his images, evidently able, with these past examples before him, to be more inventive with human form. Look, for instance, at ‘Wrestler’ (1947) and ‘Head of a Man’ (1948) in the first gallery, in which the modelling of form is compact, potent and full of character, despite the mannerist rounding of the head, which only adds to the effect.

Also in this room are a couple of strong female characterisations from the next decade, ‘Head of a Woman’ (1950) and ‘Bust of a Woman’ (1952), with a rather fine drawing of the latter sculpture hanging nearby. There are also two early nude ink studies, from the Estorick’s own collection (many of the other exhibits come from Il Cigno G.G. Edizioni Collection, Rome, or from private collections), which have a real sense of inquiry to them, rather than the undemanding formulaic depictions of later years. The Pinocchio study is in a different key, not modelled in the same way but mostly cut from sheet wax and folded into three dimensions. Greco chose to depict the key event in the story: the moment when the puppet is transformed into a boy, and he was prepared to be more experimental with materials and structures. The base of the sculpture is, for example, in quite a different openwork style from his normal approach.

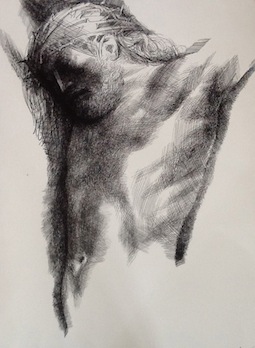

Emilio Greco: Bust of a Woman, 1952 and Christ Crucified

Emilio Greco: Bust of a Woman, 1952 and Christ Crucified

The second gallery continues with additional late drawings, though those of Christ have more genuine feeling to them. In the body of the room is a group of five rather mawkish female crouching figures from the Seventies and Eighties, huddled in on themselves and not very impressive. Even the bullfight drawing is gussied up with pastel and strong colour and doesn’t make the impression it might. I don’t know Greco’s work well enough to say whether this selection does justice to him, but a fragment of relief panel from the doors of Orvieto Cathedral, made in 1962, suggests otherwise. It is of a different order of achievement from most of the works here, and returns to the intelligent and sensitive reinterpretation of classical models that distinguished Greco’s earlier years. In reproduction, the cathedral doors (which weren’t actually hung until 1970) look remarkable, and surely deserve to join the wish list ofthings to see and places to visit. They mightalso give a better account of Emilio Greco’s talents than this slightly lacklustre show.

Pilar Ordovas continues to mount extraordinary museum-quality exhibitions in her modestly sized Savile Row gallery. The latest theme is a telling conjunction of Rembrandt and Frank Auerbach. Ordovas seems somehow to charm museums into lending masterpieces that are never usually seen in a commercial gallery space, and this show has been organised in collaboration with the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, whither the exhibition will travel (12 December 2013 to 16 March 2014). Rembrandt is represented by two paintings and two etchings: an oil on paper of ‘Joseph telling his dreams to his parents and his brothers’, with an etching on the same subject; a small oil on panel, ‘Portrait of Dr Ephraim Bueno’; and a substantial landscape etching of trees. To counterpoise these are two Auerbach paintings of heads (of EOW, a favourite sitter), an interior with figure (‘The Sitting Room’), and a trio of Primrose Hill paintings.

Two of the Primrose Hill pictures will be familiar from public collections (Arts Council and Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art), but the third (and to me the most interesting), the subject under winter sun, is from a private collection. The three present different seasons, spring, summer and winter, and allow the viewer a rare chance to compare and contrast. This is of course an urban subject, but these paintings look more like landscapes than cityscapes, being principally about space and the basic structures of the land, in which the buildings are almost incidental.

I love the idea of Rembrandt’s pictures being in dialogue with Auerbach’s, for this is what the great western painting tradition is all about. The exhibition does not make immodest comparisons between contemporary artist and Old Master, it simply juxtaposes the work of two individuals for our greater edification. Auerbach, while stressing that he cannot really put it into words, suggests that Rembrandt aims at ‘the absolute grandeur of the absolute ordinary’; or perhaps in other words, the majestic dignity of everyday appearance. In his own terms, this is surely what Auerbach also tries to paint, and what thus makes this pairing so stimulating and rich an experience.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in