Mark Mason

JFK’s Last Hundred Days by Thurston Clarke (Allen Lane, £20) brilliantly captures Kennedy’s entire life through the prism of his final months. Deliberately thrusting his crotch for an official portrait, musing about assassination (he even acts it out in a game of charades, covered in ketchup), folding his monogrammed handkerchiefs to hide the initials because he disliked ostenatious wealth, putting a black marine at the centre of a ceremonial line-up … the hero, like the devil, is in the detail.

Emailing my friend Travis Elborough about his and Nick Rennison’s A London Year (Frances Lincoln, £25), I wrote simply: ‘You bastard.’ Great idea, expertly researched and beautifully packaged (it’s even got a ribbon! No one gets ribbons these days.) Diary and letter extracts every day of the calendar — there’s Kenneth Williams and a bus driver, John Constable and Cromwell’s embalmed head, and Evelyn Waugh with a friend who says ‘West Central’ because ‘W.C.’ sounds ‘indelicate’.

Paul Johnson

No one can read, or even just look at, Lost Victorian Britain (Aurum, £12.99) without feeeling an overwhelming sadness. Gavin Stamp is our most passionate and romantic architectural historian and he describes the destruction of our Victorian heritage with appropriate anger and precision. It is amazing how much ground he covers in this book of under 200 pages, and the photographs are plentiful, illuminating and apt. The book is a model of its kind.

Blanche Girouard is an extremely hard-working, persistent and discerning young woman and her Portobello Voices (The History Press, £14.99) is a splendidly vivid presentation of the most famous Saturday-morning shopping street in the world. The people are riveting, the information is often new and strange, the language brilliantly lit up and there are jolly photos.

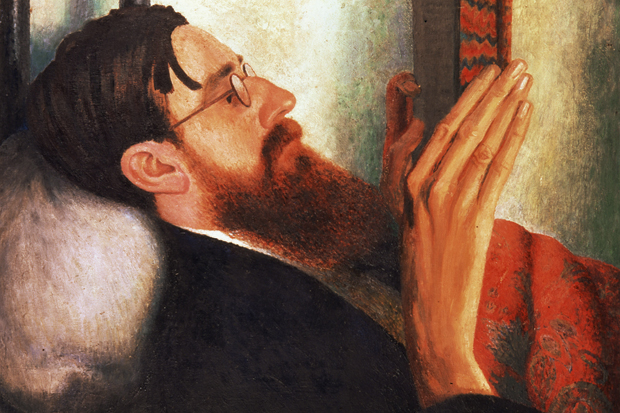

Nash, Nevinson, Spencer, Gertler, Carrington, Bomberg: A Crisis of Brilliance, 1908-1922 by David Boyd Haycock with essays by Frances Spalding and Alexandra Harris (Scala, £25). This is the handsome catalogue of the exhibition held at Dulwich Picture Gallery this summer, and I cite it for many reasons but especially because it reveals what a fine artist, particularly as a painter of portraits, Dora Carrington was. She was obsessed by Lytton Strachey, and when he died of cancer in 1932 she shot herself. She was not yet 40 and her death, we now see, was a major loss to art in Britain.

Philip Ziegler

David Cannadine’s The Undivided Past (Allen Lane, £25) is an intelligent, stimulating and invariably entertaining examination of the nature of history and humanity: it is as original as it is ambitious.

The origins of the first world war is a heavily ploughed furrow but Max Hastings’s Catastrophe (Collins, £30) is admirably scholarly yet reads as if the subject had never been written about before. No

book is definitive, but this one will be hard to better.

Jonathan Mirsky

My favourite two books this year couldn’t be more different in content and intent. Emperor Huizong by Patricia Buckley Ebrey (Harvard, £30) is the first biography in English of one of China’s greatest emperors, Huizong (1085-1135). He was a polymath — poet, painter and connoisseur of beautiful things — who died tragically, and the book is a supreme example of meticulous scholarship and eloquence.

Sleeping with Dogs by Brian Sewell (Quartet, £12.50) is a perfect, charming book about the author’s 17 dogs over almost 80 years. I hear he knows a lot about art, too.

Roger Lewis

In this ghastly virtual world of Kindles and books with batteries, hats off to Thames & Hudson, who still produce heartbreakingly beautiful volumes — books as cherishable objects, rather than books as ephemera. Perhaps realising that printed and bound literature is going the way of steamships and dry-stone walls, they have even started to publish books about books. Books: A Living History by Martyn Lyons (£14.95) starts with parchment and ends with something called ‘digitisation’ — well, shag that.

The Library: A World History by James W. P. Campbell (Thames & Hudson, £48) is another lavish and melancholy tome, as I suppose everywhere from the Codringtoni to the Bibliothéque Nationale will soon be redeveloped as drop-in centres for disabled lesbians on benefits.

May I also recommend Derek Jarman’s Sketchbooks (£28), yet again from Thames & Hudson? This facsimile of the eccentric artist and film-maker’s personal albums, with his jottings in calligraphic fountain pen, simply wouldn’t be possible on a Kindle. They belong to another time, another place.

Christopher Howse

The Survey of London started with the parish of Bromley-by-Bow in 1900, and this year it reached volumes 49 and 50 with Battersea, once a parish that covered 2,164 acres. The dustjackets of each volume (Yale, £135 for the two, edited by Andrew Saint and Colin Thom) suggest a tale of two Batterseas: the power station in one and St Mary’s church (where Blake was married) in the other. But it was housing that came to dominate the development of the parish, and the Lavender Hill mob made way, first for lodgers from overseas, then for yummy mummies with buggies as big as 4x4s.

The best book of the year, however, was Margaret Thatcher by Charles Moore (Allen Lane, £30), though it hardly needs me to say so.

Rosemary Hannah’s The Grand Designer came out in paperback (Birlinn, £14.99), a beguiling account of the poor old 3rd Marquess of Bute, who got William Burges to build the colourfully gothic Cardiff castle and then turned his attentions to Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute, an astonishing fantasy. Between a miserable childhood and death from an hereditary disease, Bute also poked his finger into ecclesiastical pies, for which he had a strong appetite.

Ferdinand Mount

It’s time to stop lamenting that Alan Johnson is not leader of the Labour party and take delight instead in his wonderful memoir This Boy (Bantam, £16.99). Named after the B-side of ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’, the book is a precise and poignant account of growing up in the Sixties in a poverty which seems unimaginable today, in a Notting Hill where the hedgefunders now roam. But This Boy also has a universal dimension, so that readers brought up on easier street will recognise the time and the terrain too. There’s no politics in it and no self-pity either. And it’s funny.

Piers Paul Read

The incidental fact that the uranium used in the first atom bomb came from Katanga enables Patrick Marnham in Snake Dance (Chatto & Windus, £18.99) to link two aspects of evil — the cruel exploitation of the Congolese by the Belgians and the extermination of 135,000 civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is a beautifully written book —informative and entertaining — that encompasses a number of different genres.

The Unintended Reformation (Harvard, $19.95), a scholarly work by the American historian Brad S. Gregory, charts how the godly Reformation led inexorably to the secularisation of western society.

The Pike by Lucy Hughes-Hallet (Fourth Estate, £25) is a masterly account of the Italian poet, playwright and political adventurer, Gabriele d’Annunzio. His love life makes him a worthy successor to his compatriot Giacomo Casanova, whose memoirs I have recently read and recommend.

A.N. Wilson

Three outstanding books stay in my mind. Rice’s Church Primer (Bloomsbury, £14.99) is written and lavishly illustrated by that multi-talented man Matthew Rice. I was going to write that it is worthy to stand beside Betjeman on your bookshelf — but it will never remain on that shelf. You’ll take it with you everywhere, and whether or not you are churchy, it will open your eyes to the variety and wonder of British churches.

Lucy Hughes-Hallett’s The Pike (Fourth Estate, £25) is a lively account of Gabriele d’Annunzio, the diminutive Italian poet, lecher and warmonger. There’s something for everyone in this book — very bizarre sex, extreme politics, European high society and sublime poetry.

Raymond Tallis writes about difficult subjects — philosophy, science, music — with absolute clarity. Reflections of a Metaphysical Flâneur (Acumen, £14.99) provides all the joy of good conversation, and each essay in the volume can be re-read with ever-deepening enjoyment.

Michela Wrong

The Idealist (Doubleday, £22.50) tracks the messianic economist Jeffrey Sachs’s doomed attempt to solve African poverty by establishing a network of model villages where his pet theories could be tested before being escalated. The author, Nina Munk, who spent six years interviewing Sachs and visiting the Millenium Villages, is a delicate, careful writer. She not only reminds us that there are good, solid reasons why certain areas of the world remain desperately poor, she raises troubling questions about the credibility of an economist embraced by rock singers and film stars.

Vibrant storytelling continues to pour from West Africa — much of it written by young women — and Ghana Must Go by Taiye Selasi (Penguin, £14.99) won my attention this year. It’s the story of an aspirational African family living the diaspora dream in the States. The sudden departure of Ghanaian father Kwaku Sai, a surgeon made to carry the can for a failed operation, shatters his wife and children’s sense of themselves. Selasi’s writing style is sometimes overly sensual and lush, but she probes the anguish of the diaspora experience with forensic attention.

Comandante: The Life and Legacy of Hugo Chavez by Rory Carroll (Canongate, £9.99). Carroll, a much-respected Guardian journalist, has great timing. His book was about to go to press when this Latin American Big Man died of cancer. It’s a bracing exploration of modern-day dictatorship which contains a merciless exposition of how a complacent middle class allowed a society and economy to be hijacked by a wily egomaniac.

Bevis Hillier

My two books of the year are a biography and an autobiography — each a gold medallist in its genre.

The biography is the first volume of Charles Moore’s Margaret Thatcher (Allen Lane, £30). Whatever you think of Thatcher, she is an unignorable historical figure. No doubt there will be many future biographers; but none of them will have the advantage that Moore was given, of being able to question her.

Unlike some biographers, Moore has put in the work. A gold mine were the letters of the young Margaret to her older sister, Muriel, sometimes about frilly underwear but including a disobliging pre-marital reference to Denis — ‘not a frightfully attractive creature’. Moore is always balanced in his assessments. I think that a biographer, when in doubt, must be counsel for the defence, not for the prosecution; but on occasion Moore is harshly critical of his subject.

He has a beautifully honed literary style, never showy, and often spiced with a wry wit. There are three things, however, missing from this volume that I would have liked to have found. First, the comment by Jean Rook, the self-styled First Lady of Fleet Street: ‘I wish that Shirley Williams did not always look as if she had been dragged through a hedge backwards; and I wish that, just for once, Mrs Thatcher might look as if she had been.’ Second, the quintessentially Thatcherian sneer at leading churchmen who in 1982 insisted on praying for Argentinians as well as English servicemen and women in the Falklands conflict: ‘Clerical cuckoos!’ And finally, some quotations from the book Writers Take Sides on the Falklands. I contributed to it, but I don’t complain from wounded amour propre. A lot of eminenti gave their views. One of them compared the Falklands enterprise with the War of Jenkins’ Ear; Michael Holroyd was pretty scathing; but Mary Renault, one of the great historical novelists, thought that ‘Of course Mrs Thatcher was right to send the Task Force.’

My second choice is Outrageous Fortune by Anthony Russell (Robson Press, £20). The third son of the late Lord Ampthill was brought up in unimaginable luxury, mainly at Leeds Castle, Kent, the home of his imperious grandmother, Lady Baillie; but no one took much notice of him. We are familiar with the other sort of story — brought up in a slum with much love — but Russell’s tale is much more unusual.

He writes superbly about life at the castle, where Lady Baillie ruled over a court of hangers-on. There is a wonderfully funny account of the launching of ducks from a motorcade. Not unexpectedly, Russell rebels against all the courtly privilege. He writes with raw honesty about his attempts at thefts and gives what might be described as a blow-by-blow account of a visit to a West End brothel, aged 17. He moved to America and became a pop singer and impresario. His friend Mick Jagger told him: ‘You will never make it in music because you are too posh, too damn spoiled, too right side of the tracks.’ Well, if not as a musician, as a writer at least I think he has a starry future.

Richard Davenport-Hines

As a devotee of Osbert Lancaster’s Progress at Pelvis Bay and Drayneflete Revealed — those gloriously illustrated studies of imaginary towns ruined by philistine developers and complacent planners — I fell with delight upon Hideous Cambridge: A City Mutilated (Thirteen Eighty-One, £18.50). David Jones’s text, accompanied by Ellis Hall’s photographs, show how a university city has been disfigured: batteries of traffic signage ruining fine perspectives, ugly street furniture, vulgar shop frontages, crass buildings with their roof-line jumble of lift-shafts and machinery, coarse materials and the boorish parsimony of some of the colleges. Though one flinches and shudders through Hideous Cambridge, Jones finds new buildings to admire and pointers for better practice. It’s a provocative book for anyone who cares about urban living.

Thomas H. Cook is a bestselling Alabama-born novelist whose psychological crime thrillers depict lives of mortifying ordinariness being ambushed by abrupt trauma or drawn into a harsh destiny. In calm, understated prose, which nevertheless sustains heart-wrenching tragedy and suspense, Cook shows compassion for human errors and wrecks. His latest, Sandrine (Head of Zeus, £16.99), about a man on trial in small-town Georgia for murdering his wife, is as taut, sorrowful and consummately plotted as Cook’s admirers have learnt to expect.

John Sutherland

Book-lovers (the two words belong together in ways that ebook-lover doesn’t) will feast on The Library, illustrated below, by James W.P. Campbell (Thames & Hudson, £48). A secondary wonder is that the publisher can serve up such a feast for under £50.

There has been a welcome trio of commonsensical books on Victorian fiction and its authors recently: Andrew Lycett’s brisk Wilkie Collins (Hutchinson, £20); Michael Slater’s thoughtfully judicious The Great Charles Dickens Scandal (Yale, £20) and Robert Gottlieb’s Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, £16.99). I congratulate myself on choosing the last, since Gottlieb reviewed my last book with a severity which would qualify it for the hatchet job of the year award.

Wynn Wheldon

Sarah Churchwell’s Careless People (Virago, £16.99) usefully provides the context in which The Great Gatsby was written. It combines the authority of scholarship with the teasing, pleasing variety of a scrapbook, and is easily the best Fitz book of this Fitz year.

In Shakespeare’s Common Prayers (OUP, £18.99), Daniel Swift demonstrates the influence of the Book of Common Prayer on the Elizabethan stage, and renders a potentially arcane subject unexpectedly compelling.

If a good book is like a good conversation, Snowdon (Gomer, £14.99) will keep you up past the dawn. Opinionated, widely read and a brilliant footnoter, Jim Perrin tells us all we ought to know about the most magnificent mountain in the British isles.

The best novel I read was Persuasion, the worst Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl (Phoenix, £7.99), both by some distance.

Lloyd Evans

Charity bookshops are beyond my purse in these straitened times. Luckily my street now boasts a fat metal recycling unit which welcomes literary treasures. Every week I plunge in my hand and pluck a surprise from its rusting gob. Beware of Pity by Stephan Zweig is a superb romantic tragedy which very nearly knocked Anna Karenina off my all-time-favourite-novel perch. I also pulled out Mein Kampf, which reveals that Hitler was a pacifist. In Chapter 26, or thereabouts, he says, ‘I call on all lovers of peace to help Germany conquer the world.’

My non-fiction pick of the year is Ann Widdecombe’s memoir, Strictly Ann (Weidenfeld, £20), whose breezy jocularity I reviewed in these pages. Widders wrote to thank me for my critique and she apologised for not contacting me sooner. With the book at the top of the bestseller lists, she explained, she’d been inundated with requests for signings and other public appearances. I couldn’t but admire this allocation of compliments. One for me and two for her.

Ian Thomson

In her zingy, razor-keen history of the Kremlin, Red Fortress (Allen Lane, £30), Catherine Merridale chronicles the political hierarchies and shifting ideologies of Kremlin life from medieval times to the present. Glorious.

The Enigma of Return (MacLehose Press, £12.99), by the Haitian poet Dany Laferrière, looks set to become one of the great poetic statements of loss and political exile. It won the Prix Médicis in France and should have attracted more attention over here.

It seems churlish to knock the Australian-born polymath Clive James, but his translation of The Divine Comedy (Picador, £25) was egregiously overrated. Plumped out with fusty-sounding words (‘whereat’, ‘aught else’, ‘folderol’), the Clive James version gives the impression that Dante wrote in an antique Italian, when he did not. Much of Dante is ‘awful’ in that archaic sense of the word (still valid in Italian) of inspiring; some versions are just plain awful.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

To be continued next week.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in