You can’t go home again, as the Americans say. It’s worth running that adage, taken from Thomas Wolfe’s unfinished novel of 1938, past those zealots who snapped up 20,000 tickets for Monty Python’s reunion at the O2 Arena in 43 seconds when they went on sale this week. Four more dates were immediately inked in, with more to follow, one feels certain, as Python fever covers the globe. What a horrible prospect.

The Python team are not horrible. Goodness gracious, no. In four BBC series between 1969 and 1974 they were often outstandingly funny, in a way that nobody had been funny before. Many of the old sketches do not work well now, and some were overrated in the first place — yes, I’m thinking in particular of that dead parrot, which is pretty Third Division. But the good stuff — novel-writing from Dorchester, Oscar Wilde and friends in Tite Street, the Australian philosophers — still stands out like a shag on a rock. As Terry Jones, playing the Prince of Wales, told Graham Chapman’s Wilde: ‘Extremely funny! We’ll have to have you up the Palace some time!’

It is precisely because the Pythons were so funny that many of us who used to be word-perfect followers wish they had resisted the urge to return for one last fling, though, as Frank Zappa said: ‘When money talks, nobody questions the accent.’ As the five remaining members (Chapman died in 1989) have all made millions several times over, that is sad. Any reunion can only be an unconvincing victory lap for a battle that was won four decades ago. The sketch suited them best. Their films, while intermittently funny, did not represent their strong suit, and the end of the overrated Life of Brian, with that infantile song that has somehow gained common currency, was the worst thing they ever did. No wonder Eric Idle was entrusted with the job of singing it. He was only ever quite funny, and since he went to live in California he has ceased to become even that.

Still, we can forgive him for being there when the bang-shoot started in 1969, and what a bang it was. A controlled explosion, more like, as three Cantabrigians and two Oxonians were thrown together to make a series of exploratory late night shows. Chapman and John Cleese had worked on At Last The 1948 Show with Marty Feldman — it’s where the Four Yorkshiremen came from. Jones and Idle had collaborated with Michael Palin on Do Not Adjust Your Set. Terry Gilliam, an American, was brought in to add a layer of visual nonsense, and almost overnight a team had taken shape: a Real Madrid of comedy, with Cleese, the most striking performer, cast as Alfredo di Stefano.

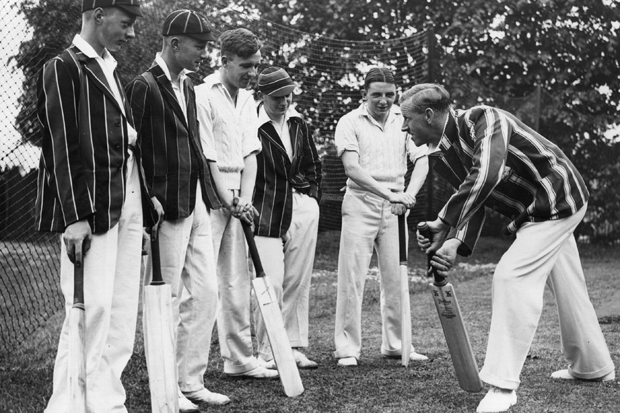

The most extraordinary aspect of Python’s international success is the Englishness of the humour. More specifically it is the humour (‘Who threw that slipper?’) of the English public school. Cleese went to Clifton, Palin to Shrewsbury, and the other three were scholars at old-fashioned grammar schools. Jones and Idle were head prefects. They had all grown up in a small-c conservative world, very unlike the one today’s ‘liberated’ jokers inhabit. Python was a middle-class thing, rooted in college quad and JCR. Even now, 44 years since the balloon went up, you will find very few working-class people who get it.

So when people talk about the Python gift for subversion, it is a very English subversion, expressed in many forms down the years. It belongs to the time-honoured tradition of sending up those institutions and people that we hold (generally) in affection. In that respect they were successors not only to the Beyond The Fringe team, who had opened up new ground, but also to Gilbert and Sullivan. It isn’t such a big step from I Am The Ruler of the Queen’s Navee to the Upper Class Twit of the Year Race. Except Gilbert is sharper.

In contrast to so many modern comedians, shoehorned into television careers after a few nights on the Edinburgh fringe, the Pythons were not angry people trying to right wrongs. They did not assume political or social positions. They were about as apolitical as it is possible to be, in costume and out of it. They were licensed fools who, like the Beatles before them (and for once that much-quoted parallel is appropriate) found themselves at the heart of a phenomenon they may not quite have understood. They did not seek to change the world, but the world changed around them, and they have our gratitude.

Which is why they should have stayed apart, and left us with our memories. Already you can hear people quoting Python sketches verbatim, and however funny they were they were only ever funny in the mouths of the five people who wrote them. Some of the showbiz tributes showered on them in the past week have churned the stomach, too. If they invite the likes of Eddie Izzard to swell a scene or two when the show hits Docklands next July, it really will be time to send for the water cannons. You should have organised a nice dinner in Primrose Hill, chaps, and thrown food at each other. You can’t go home again.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in