The title of the Lisson Gallery’s new show, Nostalgic for the Future, could sum up the gallery’s whole raison d’être. From its inception in 1967, the Lisson has championed the cutting edge, providing a British and European platform for the major conceptual and minimal artists from the States — Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre and Dan Flavin among them — and following that in the 1980s with its promotion of New British Sculptors such as Anish Kapoor and Tony Cragg. While this generation wittily subverted the material world to question our position within it, their heirs in turn seem more interested in querying the position of art in the world — still subversive, but more hermetically so. There’s an anomie in the most recent works here by Haroon Mirza, Ceal Floyer and Ryan Gander that arguably turns in on itself, leaving the viewer floundering for meaning.

So, here we have something of a smorgasbord — a reconfigured version of the show originally staged in Sao Paulo to present Lisson’s impressive line-up of artists in some meaningful pattern of influence and inspiration. It opens with a series of agitprop posters from 1977 by the collective Art and Language, reminding us of the gallery’s radical credentials, and nearby the pulsing laser of Jonathan Monk’s projected mantra ‘Nostalgic for the Future’ indicates that we are in for a time-travelling rollercoaster of a ride. And so it turns out: Tony Cragg’s towering accretions of machine parts, ‘Minster’, acts as turret gateway to a display that hovers indecisively between the concrete and the evanescent.

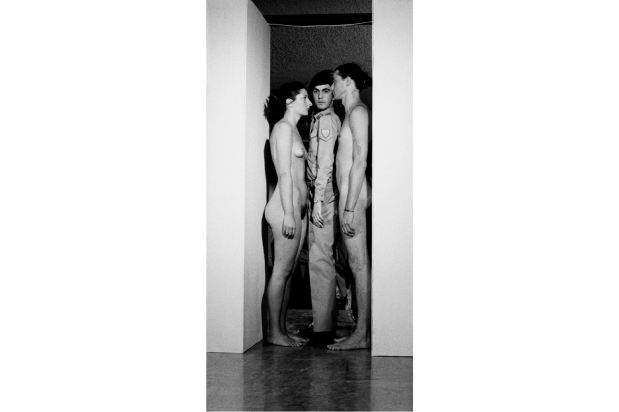

Jonathan Monk: Something to see something to hide, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

Jonathan Monk: Something to see something to hide, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

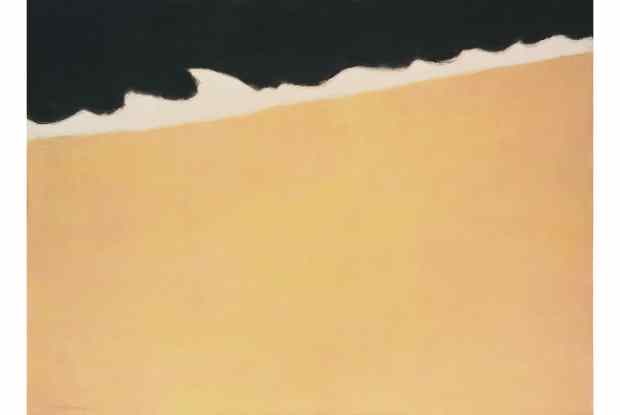

Concrete is indeed the medium chosen by Anish Kapoor for his bizarre extrusions, the chosen example like some florid tutelary deity spilling out of its throne on to the plinth beneath. Its gross materiality seems an affront to the minutely worked delicacy of Shirazeh Houshiary’s gauze-like ‘Flood’, shimmering nearby. Houshiary, an Iranian-born artist living in London, creates in her paintings intimate webs of pencil-stroked patterning that evoke breath, the very essence of life, and by implication its opposite. What a pity that one of Kapoor’s many variations on the void has not been included; Richard Long’s ‘Grey Slate Spiral’, however, goes some way towards bridging the gap, its stark physicality on the gallery floor setting off the archaic resonance of its spiralling form.

These are all works built up, laboriously constructed out of the material world; now fast forward, and the last gallery contains their mirror opposite. Here, Angela de la Cruz has comically — or tragically? — debunked the whole notion of painting: a canvas has been violently mugged and laid out flat, covered with a white shroud, while our old friends Art and Language have taken another painting hostage, defacing it with illegible script before clamping the smeared composite behind glass. Domestic violence is also perhaps implicit in the broken plates that Richard Wentworth has strung together along the walls, while the glazed ceramic elements of Richard Deacon’s ‘Border Traffic’ look like nothing so much as dismembered vertebrae scattered on the floor.

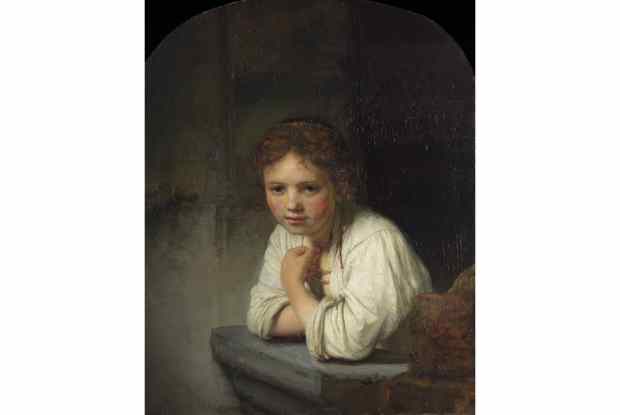

Angela de la Cruz: Deflated. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

Angela de la Cruz: Deflated. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

Between these opposing principles of accretion and destruction are others: the urban/rural divide is nicely evoked by Julian Opie’s stacked tower blocks and vinyl cityscape — all monochrome slick and chic — alongside Cragg’s ‘Leaf’, a collage of foraged plastic, comprehensively uncompostable. And Ceal Floyer evokes both the wild and the tame with her flock of flattened birds strewn across the gallery’s plate-glass windows, innocent interlopers from the blue beyond.

To get to the heavy rhythms of Haroon Mirza’s ‘Preoccupied Waveforms’ in the basement you have to brave the menacing shower of arrows that compose Ryan Gander’s installation, and both put you on your mettle. We’re no longer spectators, we’re now participants, but in what exactly? Mirza’s buzzing and LED-lit environment seems to have a life of its own, a hermetic system endlessly regenerating itself, so we don’t have much of a role there. Gander’s mystifying scenario asks for our engagement but offers no context for it. We’re back to Minimalism, albeit a busy and, in Mirza’s case, noisy form of it. Is this nostalgia for the future? If so, some observers may well hark back with more nostalgia to a recent past, one where artists set out to communicate beyond the bounds of the largely solipsistic world they inhabit.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in