While reading this book I was reminded of the great ‘scandal’ among New York’s intelligentsia in 1982 when the then beauty queen of the left-literary world, Susan Sontag, speaking in support of Polish Solidarity, delivered herself of what would have been a truism to most ordinary people but came as a bombshell to her audience of ‘progressives’ in the Town Hall: ‘Imagine, if you will, someone who read only the Reader’s Digest between 1950 and 1970, and someone in the same period who read only [the left-wing] Nation or the New Statesman. Which reader would have been better informed about the realities of Communism? The answer, I think, should give us pause…’ The same point could have been made if we used local equivalents.

Even though the Sontag row was a long time ago, nothing comparable has taken place among Australia’s ‘intellectual Left’, and this book and its context goes a long way to explain why. It’s a curious, provocative and multilayered book: variously a memoir, an examination of a galaxy of strange characters and, most strikingly, a perverse commentary on the Cold War viewed from Moscow and Oxford through a very murky Australian, and particularly Melbournian, lens.

It’s written by an accomplished, internationally prominent Sovietologist, Sheila Fitzpatrick, for the past 20-odd years based at the University of Chicago. Born and bred in Melbourne, she is the daughter of a once prominent left-wing writer, Brian Fitzpatrick (1905-65). Intellectually gifted and musically talented, she left Australia in 1963, Melbourne degree in hand with some Russian, for postgraduate studies at Oxford, keen to escape both family and country.

Brian Fitzpatrick — a journalist, fellow-traveller and economic historian — displayed a polemical turn of mind and a Marxist sense of history and morality. An active if selective civil libertarian and gregarious boozer, he argued that ‘exploitation’ and the English were two sides of the same coin. He and his coterie make for quite a story, chronicled by the author in her earlier unreliable memoir, My Father’s Daughter (MUP, 2010).

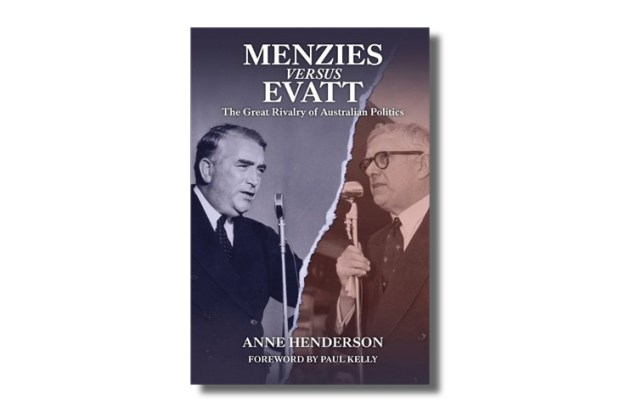

The title of this second volume of memoirs provides the thread that runs through the book — espionage and the idea of truth in history. The author’s first exposure to spying was as a small child listening to her father as he became more deeply immersed in Australia’s very own Cold War spy scandal, the Petrov affair in the early 1950s. Revolving around the defection of two experienced cypher ‘diplomats’ from the Soviet Embassy in Canberra, it flushed out a nest of locally groomed spies and a caravan of fellow-travellers, almost all well-known to Brian Fitzpatrick. The fact that many of them really were Soviet spies didn’t bother Brian as he was already ideologically on side. Besides being an advisor to the accused, he was also the confidant of ‘Doc’ Evatt, then Leader of the Opposition. Whether as a consequence of Fitzpatrick’s advice, not implausible, or of his very own creative imbecility, Evatt declared in Parliament that he had asked his friend, Soviet Foreign Minister and Stalin protégé Molotov, whether it was true the Soviets had engaged in espionage in Canberra.

The resulting derision effectively destroyed Evatt’s reputation while assuring Menzies’s long reign. On this key issue in her family’s history, Sheila Fitzpatrick’s assessment that the accused were no doubt innocent because no charges were laid is quite breathtaking: so much for her much-vaunted research skills! In reality, US signals intelligence, known as the Venona decrypts and released in 1995, leave no doubt as to the guilt of the key principals; their arrest and subsequent trials would have fatally compromised this code-breaking triumph.

The Melbourne launch of the book was chaired, appropriately, by Melbourne University Professor Stuart McIntyre, the smooth-talking, somewhat unctuous doyen of ‘progressive’ history, known for his capacity to shelve his legendary ‘cool’ whenever Aboriginal history, or the supposed ‘McCarthyist’ persecution of fellow (left-wing) academics, is raised; but his indignation is strangely muted on the subject of the mass murder of tens of millions in the name of the cause which seems to have stirred his scholarly imagination for a few decades now — Communism. These days of course the ‘revisionists’ only believe in anti-anti-communism: it’s less painful than the real thing but still morally uplifting.

Melbourne University deserves full credit for making a distinctive contribution to the cause of ‘demystifying’ the Communist threat from the 1940s onwards: there was Ian Milner, a known Communist in his native New Zealand and Oxford, head of MU’s political science department for the key years of the second world war, later a Soviet agent responsible for smuggling bundles of secret Allied documents out of Foreign Affairs from 1945 and who defected to Soviet-dominated Czechoslovakia in the early 1950s. It was Milner who gave that legendary mystic Manning Clark his first academic job at MU in 1944, and Clark repaid his friend by making multiple trips to Prague after Milner’s defection to see him, and in 1960 published Meeting Soviet Man in which he confessed his devout belief in Lenin’s divinity.

More recently, Melbourne had a professor of history, Stephen Wheatcroft, a ‘revisionist’ dedicated to massively reducing the estimated death statistics of Stalin’s ‘terror famines’ (the original figures are Robert Conquest’s). Interestingly, one notable MU academic who challenged this cosy campus orthodoxy and, unlike his critics, knew the reality of Communism first hand, the late Dr Frank Knopfelmacher, is rudely dismissed in a new biography of political science Prof MacMahon Ball, although there is no mention of Milner even though Ball hired him! Originally a PhD thesis, the author was supervised by the ubiquitous Stuart McIntyre.

Back to the book. Sheila goes off to Oxford in the mid-1960s, specifically St Antony’s College, then as now the leading postgraduate college focusing on international studies. She tells us, several times, she doesn’t like England, even though she’s on the verge of marrying someone with a British passport which she candidly concedes is so she can get her own in order to secure a British Council grant to study in Russia. Although everyone in England seems to be falling over themselves to be kind and co-operative, nothing is good enough for our Sheila. And why? Well, she’s unhappy St Antony’s is labelled ‘the Spy College’ in the odd tabloid sensation, scandalously the Russian experts speak Russian and ‘the Warden’ was once a British agent, in fact a hero fighting Nazis. All this spy talk, she believes, might prejudice her access to Soviet documents. She also abominates their ‘Cold War bias’.

Sheila’s thesis is on Stalin’s cultural supremo, a man called Lunacharsky, who no one outside of the Kremlin and the odd Sovietology conference has ever heard of, or would want to. Sure, he’s a true Leninist and loyal to Stalin and over time has probably overseen the slaughter of thousands but these are the ‘compromisers’ we’re told by Sheila that ‘one has to resurrect’.

She overflows with gratitude for Lunacharsky’s stepdaughter and particularly his younger brother-in-law and secretary Igor, whom she sees as a father figure (early onset ‘Stockholm Syndrome’?), a man proud to call himself a true Leninist who respected Stalin. But, and one just can’t miss it, there’s nothing but sneers and smears for all the anti-Communist players in Sheila’s coming of age Cold War melodrama.

In her seemingly instinctive Anglophobia she dumps on fine people and institutions, in contrast to her fawning over obscure Communist apparatchiks who she needs to quench her formidable academic ambitions; but that’s fine because she’s told us she’s at the cutting edge of a whole new academic subdivision called ‘revisionism’, which she clearly sees herself as leading, all the better presumably to cast aside the tired concept of totalitarianism, and with it those tiresome ‘traditionalists’ like Robert Conquest, Richard Pipes, Vladimir Bukovsky, Czesław Miłosz, Leo Labetz, Leszek Kołakowski and Andrei Sakharov. The good news is that as long as the moral comparison of Nazism with Stalinism is seen as compelling — as in such powerful books as Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands (2011) — the obstacles to diluting, obfuscating and domesticating the Soviet nightmare with a dose of ‘revisionism’ are still great.

In Putin’s Russia, where almost half the population still admires Stalin, one supposes there is genuine demand for a new kind of ‘revisionism’. The spreading contagion is now called ‘gulag denial’ and this Melbourne export can justly claim, objectively speaking that is, to have made a significant contribution.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in