I’ve worked for the BBC for years and have been listening to the Today programme all my adult life, but joining it as a presenter feels like exploring a new frontier. Being on top of your brief is one thing; the mechanics of a three-hour live radio programme quite another. Take the junctions leading up to the ‘pips’ at the start of each hour. From television, I’ve been accustomed to directors counting presenters down to these junctions while they ad-lib on air — the idea being to stop talking as the voice in your ear says ‘zero’. But radio presenters are pretty much on their own, watching the clock and navigating to a precise target of five seconds to the hour. To my presenter colleagues, all this comes naturally. To me, at present, it feels less like navigating and more like hurtling towards a roadblock in a speeding car. And then there’s the other time-related issue on Today — telling it. I already knew the importance of the on-air time checks. At my home on a school day, the end of breakfast must be in sight by ‘Thought for the Day’, and we’re all in trouble if shoes aren’t on by the eight o’clock pips. So I understood the alarm of a listener who tweeted one morning to say I had caused him to panic by announcing it was a quarter to eight when it was only a quarter to seven. I felt only marginally better when one of my Today colleagues generously said it was ‘surprisingly easy’ to get the hour wrong. Another listener has taken a more active approach, emailing in a bespoke website designed to assist Today presenters. The screen displays just two lines of text — one with the date and the other with the exact time written out in a full sentence and changing on every minute. Much appreciated.

Today, of course, dispatches its presenters out of the office when the story requires — which is why I found myself on a train to Portsmouth after the BAE announcement ending shipbuilding there. My interviewee was one of the 940 people losing their jobs at the shipyard. We met by the harbour, where he carefully pointed out all the landmarks he had come to know so well, including the magnificent HMS Warrior — the Royal Navy’s first iron-clad warship. The announcement had come as a terrible shock to him, changing all his hopes and plans for retirement in an instant. But as we stood on the quayside, there was so much pride at having been part of a great industrial tradition and a highly skilled workforce. As I travelled home that evening, I remembered his vivid description of how it felt to build a new ship and then see it launched into the water — a sight now forever lost to him and his colleagues.

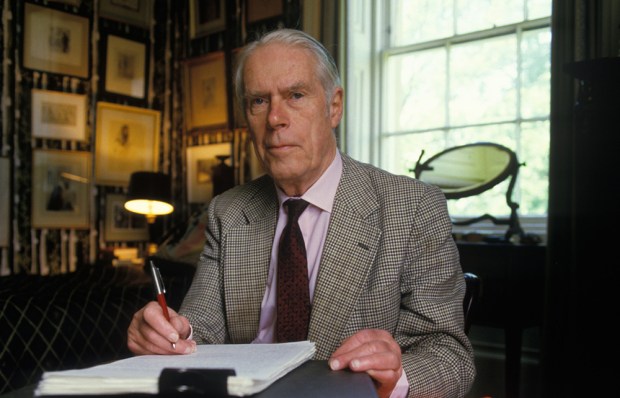

Violette Szabo, an S.O.E agent who worked out of Tempsford

Violette Szabo, an S.O.E agent who worked out of Tempsford

The village of Tempsford in Bedfordshire is one I have come to know from having family in the area, but I have only recently discovered that during the second world war it was home to one of Britain’s most secret airfields. From here, agents of the Special Operations Executive and the other secret services were sent into occupied Europe, with flights going back and forth on the moonlit nights of every month. The barn where the agents waited to board their planes is still there, off the beaten track but visited every Remembrance Day by veterans and their families. Many who flew from RAF Tempsford never returned, and in the stillness of the barn, you can only imagine the mixture of emotions they must have experienced as they waited. Among them were 75 women, whose names and nationalities reveal a surprisingly international line-up. Most were British and French but others included four from the Soviet Union, two Americans, two Germans, two Poles, Dutch and Belgian agents, as well as an Indian and a Chilean. Almost half of these women were captured and 16 executed. Now they, and others who played a key role in Special Operations, are being commemorated with a memorial in the village. It will be much more visible to passers-by than the old airfield and barn, which means that 70 years on, Tempsford’s wartime record will now be less hidden.

Sachin Tendulkar (Photo: Getty)

Sachin Tendulkar (Photo: Getty)

Many memories of Sachin Tendulkar have been shared over the past ten days as he said goodbye to international cricket with a final Test in Mumbai. The greatness of his record on the pitch was matched by the words he used in farewell — generous to his family and his fans. Sachin’s reputation has always been that of a grounded man, remarkably unswayed by his godlike status in India. Abroad, he can probably have something closer to a private life, but anonymity is impossible, at least in any cricket-playing nation. Last summer, my sons came face to face with him at the indoor nets at Lord’s and he was gracious in posing for a picture, despite being in the middle of coaching his own son at the time. In his sporting prowess and his manner, he will remain an example to his sport and beyond for a long time to come. And that photograph will be treasured for a long time, too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Mishal Husain became a regular presenter on BBC Radio 4’s Today last month.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in