Since I was a child, pretty much everybody I have ever met has asked me if I want to be a politician. The answer has always been no. Once, at university, I dimly remember giving this answer with so much vigour and conviction that I was escorted from the room, and the guy I’d given it to — an almost perfect stranger — came back to find me the next day, to apologise for asking in the first place. Even these days, the phrase ‘follow in your father’s footsteps’ drifting across the table at a dinner party can cause my wife to shoot me a warning look. My point here being, it’s never been ‘maybe’.

Eventually, I suppose, the question will switch to the past tense, and people will ask whether I never wanted to be a politician, and I will feel old. But not, I think, regretful. The question irritates me for a bunch of reasons, but chief among them is the presumption it makes about my politics. Because what they expect, of course, is not only that I might want to be an MP, but also that I’d necessarily want to be a Conservative one.

This is annoying on a personal level — especially these days, when my general un-Conservativeness is hardly something I keep bottled up — but also, at the risk of sounding pompous, on a philosophical level, too. I’m similarly annoyed when those on the left start shouting about their familial credentials — parents on picket lines, grandparents founding members of institutionally angry working men’s organisations in Doncaster, etc — because I simply don’t grasp what difference it ought to make. Bluntly, if your politics are not the outcome of your own independent thought process, I don’t particularly see why they should be of any interest to me. This isn’t football, you know.

Of course, for all that, politics often is hereditary, at least in terms of compulsion. Much has been written, lately, about the tribe of New Labour princelings — Euan Blair, Will Straw, Emily Benn and the slightly older David Prescott — all of whom seem to be on the verge of parliamentary careers. Generally, this is labelled as nepotism, which is lazy and not terribly fair. It took another Labour brat — Dan Hodges, the son of Glenda Jackson, now a Telegraph columnist — to point out that, New Old Labour being what it is, having an Old New Labour surname is probably more of a hindrance than a help. But for some, politics is the only world.

Not for me, though, and I’d be lying if I pretended this was only because no party seems like a natural fit. People shape their parties, after all, and sometimes dramatically. But for me — and there’s simply no nicer way of saying this — I can’t be arsed. The process of politics does not appeal, and the results are not something I crave enough to want to endure it. This is not how I want to spend my precious time. So here I sit, content instead just to bitch about those who feel differently.

The thing is, this is my problem. It’s not politics’ problem. There is a system, and if I cared enough — if I had humility enough to do thankless things and pretend to care about them, and send leaflets, and knock on doors, and make endless small talk, and not mind terribly when people stabbed me in the back, and almost certainly do a fair bit of stabbing myself — then, if I was lucky and if I was good enough, I could contribute towards changing that system. Be the change, as I think Mahatma Gandhi said. Drive the moneychangers from the temple, like that other bloke. But I don’t. And so I don’t.

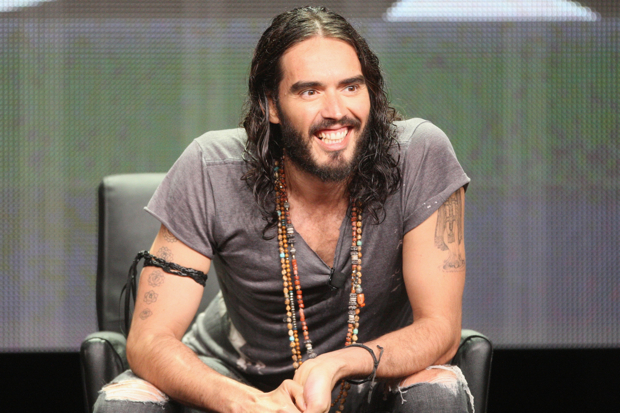

Mea culpa. This is apathy. This is the subtext when people like Russell Brand — and this week even Jeremy Paxman himself — moan on about a political system blind to the needs of ‘ordinary’ people. It’s a worldview that hinges on a concept of ‘us’ and ‘them’, but makes no effort whatsoever to become ‘them’ and do things any differently. I will take a lecture on the distant political class from somebody who has tried to penetrate that class and failed, and I will be told ‘they’re all the same’ by somebody who has not only done that, but then tried to be different, and crashed back to earth as a result. Not, though, from people who simply don’t like what they see, and want somebody else to do all the work. I mean, honestly. Lazy sods.

Power play

To a studio on Chancery Lane, the other day, to debate the Forbes Power List with another British journalist and a very peculiar and angry Russian man. This was for the Voice of Russia, which is basically the Kremlin’s answer to the BBC World Service. What has happened, you see, is that Forbes, which publishes a list of the most powerful people in the world each year, has stuck Varnished Vlad at the top, instead of Barack Obama.

My contention was that this was actually a good thing for western democracy and the world. Well-functioning countries, was my point, are not led by powerful individuals. Rather, they function with systems of checks and balances in which individual power is limited. Naked, chest-thumping power, I argued, was the preserve of tyrants.

To be honest, I was mainly trying to irritate the Russian guy. As I spoke, though, I had the strange sensation of realising I was entirely right. Doesn’t happen often.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Hugo Rifkind is a writer for the Times.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in