Marianne Moore’s poems are notoriously ‘difficult’ but her personality and the circumstances of her life are as fascinating today as they were to the avant-garde writers and artists of 1920s New York. Much of the fascination lies in the contrast between what Linda Leavell calls Moore’s ‘maiden-aunt persona’ and her position as a ground-breaking modernist, whose highly idiosyncratic verse and technical experimentation dazzled and baffled her contemporaries.

She was fragile, nervous, shy and had difficulty eating; an invitation to tea might ‘knock her up’ for days, but as editor of The Dial from 1925-1929, with ‘a paradoxical combination of self-assertion and self-effacement’ she was a powerful figure at the centre of modernism, and in her life, as in her poems, she embraced modern American culture, high or low, with ‘gusto’ — a quality she regarded as essential in art.

Her wit, ‘the unpredictability of her views and her diamond hard … observations’ brought her many admirers, Ezra Pound, T.S.Eliot — the first promoters of her poetry — William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens among them. And as another poet Randall Jarrell observed ,‘in spite of a restraint unparalleled in our time, [Miss Moore] is a natural, excessive and magnificent eccentric.’

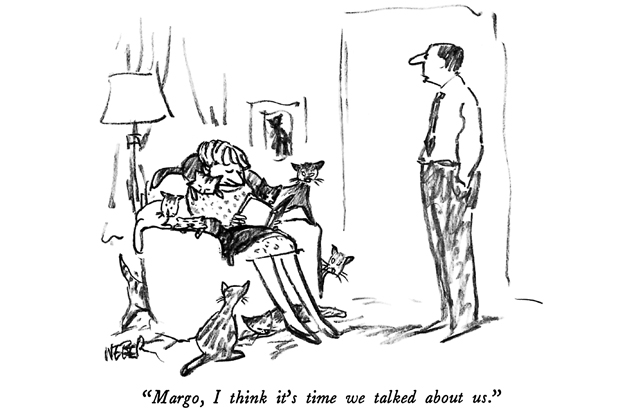

She never married, ‘apparently never fell in love’, but lived with her mother for 40 years in conditions of appalling intimacy and apparently quite unnecessary frugality (sharing not merely a bedroom but a bed). Mother and daughter are described by one observer as ‘an anachronism … characters out of a Victorian novel misplaced in the modern frenzy of New York’. For five years these punctiliously formal, genteel and high-minded ladies ate their meals sitting on the edge of the bath. (And what meals: onions and prunes; for a guest, ‘cooked apples, canned corn, salad dressing and cocoa’).

Her friend and protégée Elizabeth Bishop describes Moore as ‘one of the world’s great talkers’; she also calls Mrs Moore a very good cook, which suggests perhaps that these strange meals (described in the lively, teasing three-way correspondence with which the adored brother Warner was daily yoked to mother and sister) were just a family joke among many others in a private language baffling to outsiders. The story of Warner’s achievement of an independent life and happy marriage in the teeth of his mother’s outrageous interventions (she was an emotional blackmailer second to none and ‘fierce opponent of most heterosexual unions’) is a riveting subplot.

Moore’s ‘pathological’ devotion to her mother ‘annoyed and mystified’ her literary friends, but she repelled many attempts to rescue her and insisted that the confined life she led provided the perfect conditions for writing — she is a splendid example of Leonardo’s dictum that ‘Art breathes from containment and suffocates from freedom.’

After her mother’s death in 1947 Moore became a much-loved celebrity (famously throwing the first pitch at the Yankee stadium in 1968), a position she enjoyed. But it is generally agreed that the poetry suffered — including her early poems, which were ruthlessly revised.

An extraordinary photograph of mother and daughter by Cecil Beaton shows Marianne looking battered and almost cowed and much the older of the two; but whether Mrs Moore understood the poems or not it is clear that Marianne valued her (sometimes scathing) comments and her assistance in what was in a way a joint venture. ‘Marianne and I are like a wigwam of two sticks’ she said when both were ill, as they often were — like her daughter she had a vivid turn of phrase and much humour.

Although acknowledging that ‘Moore’s poetry does not invite biographical interpretation’, Leavell mines the early poems for references to events in the poet’s life and evidence of ‘profound feelings’ that Moore herself revealed to no one. While this occasionally seems far-fetched, this first authorised biography is notably level-headed and clear, with much new information about Moore’s family and early life, health, finances and the father she never knew.

With permission to quote from the archive, a benefit denied Moore’s first biographer, Charles Molesworth, in 1990, Leavell is able to provide a deeper psychological study of this ‘wonderful, amazing and delightful creature’, as Elizabeth Bishop called her.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £24. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in