For much of its history the Danube has been a disappointment. It looks so tempting on the map but, far from being a natural motorway for trade and ideas, its sheer awkwardness has thwarted generations of visionaries, engineers, soldiers and dictators. Freezing up, expanding into baffling flood-plains, racing through narrow defiles and randomly scattered with dangerous islands and hidden rocks, it has at best tended to function only for fishermen and the most local trade.

Until the 19th century there was the additional problem, from a western point of view, of its lower reaches having Turkish owners who, as customers, had the disadvantage of wanting to kill or enslave everyone upriver. The 20th century saw the Danube blocked up in both world wars, broken in two by the Cold War, blocked up again in its Yugoslav stretches by devastated bridges in the 1999 Nato intervention and occasionally poisoned for hundreds of miles by chemical spills. As with the Rhine, we have today inherited a dammed, embanked, straightened, ecologically devastated version of something that once used — within the constraints of Europe’s climate and fauna — to be almost as wild and exotic as the Amazon.

Nick Thorpe’s wonderfully expert and thoughtful new book manages to deal with all these disasters while enjoying too the Danube’s surviving oddities and beauties. The book is a record of Thorpe’s journeys along the river from its Black Sea delta to its source, using various forms of transport and interrupted by a horrible bike accident in Budapest. Deciding to begin at the Danube’s mouth makes the whole book possible.

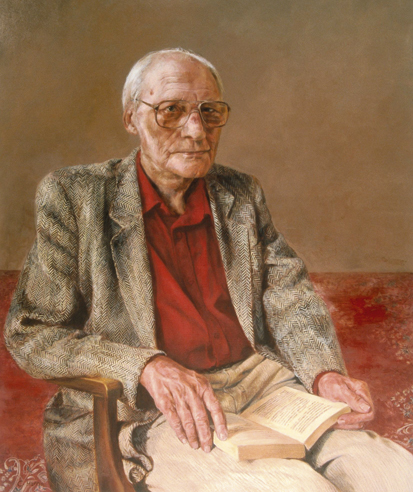

Hanging over the project is Claudio Magris’s overwhelming, omnivorous Danube (1986), which effectively owns the entire watershed when travelling from west to east, beginning at its origin in a ‘sodden meadow’ in Swabia. Thorpe avoids writing a mere commentary on Magris by starting out in the river’s far east, on the Black Sea, and heading west. Rhetorically this is useful too, as it allows him convincingly to talk about the river’s Europeanness in even its notionally most woolly and remote stretches.

Thorpe has lived much of his life in Hungary and as a journalist has an almost unerring ability to home in on interesting interviewees. He flounders around among reed islands with garrulous fishermen, talks to copper-smelting Roma and — in a truly extraordinary passage — visits Europe’s last traditional leper colony. One of the many pleasures of The Danube is the way that, with the author so completely fascinated by the ethnically mixed region around the river’s delta, the book rapidly becomes an organisational shambles. Here he is, in a manageably short, 272-page book, still munching catfish and talking to a Delta Tatar on page 70. At this rate the book will need to be some 4,500 pages to make it to the Danube’s source. As Thorpe ruefully admits, ‘I begin to worry if I will ever make progress upstream’. But his floundering is a great source of strength — the reader knows that he will only encounter things that the author particularly values and that he is in safe hands rather than those of some mad encyclopaedist.

As it turns out, what Thorpe really values are the often little visited reaches of the river from Romania and Bulgaria to Serbia and on to Hungary, with the book only dealing in a cursory fashion with Austria and Germany. Perhaps this is in part because of the author’s injury, but more importantly because places like Regensberg and Passau are well known and rather worn flat, whereas Thorpe could not be happier than when chatting to some women harvesting paprika or wandering around the Bulgarian river port of Lom. In a particularly striking passage he talks about the Roma who live in Lom and the complex pan-European world that has opened up to them since the end of the Cold War. He talks to a Roma girl, a student whose family have lived in both the Czech Republic and Bulgaria and who was on a Roma medical scholarship granted by a foundation in Budapest.

The book may be full of examples of poverty, discrimination and general post-industrial grimness along the river, but for this student and for many of Thorpe’s other interlocutors, there is still an all-pervasive sense of relief at post-Communist normality. The prison camps along the river are closed, nobody is shot for trying to swim across the Danube from one country to another, nobody is forced to paint the leaves of dead trees green to cheer up an inspecting dictator.

The Danube is not without its faults. Alliteration and simile stalk the land, and Thorpe has a weakness for some dull-sounding old civilisations, with all their pots and figurines tangled up in the usual nationalist junk about whose noble-browed ancestors these belonged to. I felt a bit sad too that he fails to mention Esztergom’s Danube Museum, with its member of staff who can, with weird accuracy, mimic the cries of the river’s wildfowl. But these are minor complaints. The Danube may never have lived up to its promise of becoming one of Europe’s great commercial arteries, but as an organising principle for an inspired book, it works beautifully.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.95. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in