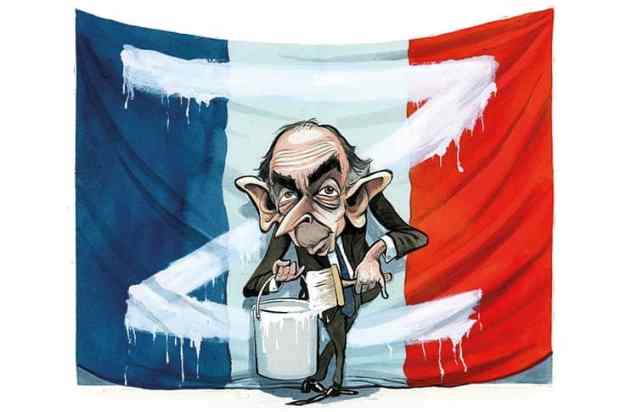

What happened to the cheese-eating surrender monkeys? Just over a decade ago, the French, having refused to join the allied adventure in Iraq, were the butt of every hawkish joke. (Remember ‘Freedom fries’? Oh how we laughed.) Now, as America and Britain are beating a retreat from the world stage, France has turned into the West’s most reliable interventionist. Its President, the disaster-prone François Hollande, rattles his sabre at any despot or war criminal who dares to stand in the way of liberté, egalité, or fraternité.

American neoconservatives — the War Party in Washington — have turned Francophile as a result. ‘Vive la France!’ tweeted Senator John McCain, America’s most insatiable hawk, after the French tried (unsuccessfully in the end) to scupper the deal between the world’s leading powers and Tehran over Iran’s nuclear development programme. ‘Thank God for France,’ added Senator Lindsey Graham, another arch-neocon, ‘The French are becoming very good leaders in the Mid East.’ One contributor to the right-wing American magazine the National Review suggested that President Hollande should run for the White House in 2016.

It’s a bizarre volte-face. Where America’s interventionist lobby once commended President Bush for standing firm in the face of Gallic pusillanimity, now they berate Obama for leaving it to France to lead the free world. Obama is mocked for ‘leading from behind’. Britain is a diminishing player, humiliated by our failed exertions in Iraq and Afghanistan, and unwilling to step up. Germany remains reluctant to wage wars, for obvious reasons. So it has fallen to France to take the initiative in the fight for global democracy.

Look at many of the world’s trouble spots, and you’ll see French forces on the offensive. Only last week, France sent a further 1,000 peace-keeping troops to the Central African Republic. This is on top of an ongoing and increasingly difficult French military campaign in Mali; a small but significant intervention in 2011 in the Côte d’Ivoire, and, in the same year, France’s leading role in the removal of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya.

In Syria, too, France has been gung-ho for action. After David Cameron’s bid for intervention was rebuffed in Parliament, it looked for a few days as if France and the US would take on President Assad by themselves (with a little help from a few minor players). Secretary of State John Kerry made some rather gushing statements about France being his nation’s ‘oldest ally’ — the insinuation being that the relationship between America and Britain was not so special after all.

Hollande’s gusto in foreign affairs is partly about preserving France’s traditional sphere of influence in North Africa, even if he is keen not to be accused of being a neo-colonialist. He talks about forging ‘partnerships’ with democratic forces — not about civilising les sauvages — but the result is that French soldiers are still busy fighting on several fronts in their old empire. There is also the matter of righting old wrongs, and assuaging guilt. The French are haunted by their legacy in many parts of their empire, as well as by their country’s apparent complicity in the Rwandan genocide in 1994.

French politicians are insecure about their country’s waning significance, too. Like Tony Blair and David Cameron, France’s governing elite are fond of posturing on the international stage, because that makes them feel like world leaders — when deep down everybody knows that, despite Obama, Uncle Sam still calls the shots.

It is also clear why Hollande, so desperately unsuccessful at home, might go in search of monsters to destroy abroad. His approval rating hit a new low of just 15 per cent last month, and Standard & Poor’s recently downgraded France’s economy again from AA+ to AA. Perhaps a quick and decisive win in the Central African Republic will give the French President a little boost ahead of 2014.

But this new bellicosity is bigger than mere political concerns or any wish for France to be the ‘gendarme d’Afrique’. Under President Sarkozy and now under Hollande, the French have moved away from the hard-headed realism of De Gaulle, Mitterrand and Chirac towards a more aggressively liberal outlook. Sarkozy reportedly suggested that, had he been president in 2003, he would have supported the invasion of Iraq, and his long-serving foreign minister took a consistently hawkish line against the mullahs in Iran. Hollande’s government might have been expected to swing back towards the peaceniks, but in fact it has taken Sarkozian internationalism to new extremes. The French ambassador to Iraq recently promised that his country would help prop up the fledgling democracy in Baghdad by providing arms and training to local security forces. Hollande’s unwillingness to compromise with Tehran has made him popular in Israel, if not in the banlieues of Paris. When Hollande visited Jerusalem last month, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu laid the praise on thick. ‘Vive la France! Vive l’Israel! Vive l’amitié entre la France et Israel!’ he said. ‘The soul of France is equality,’ he said.

Ah, l’egalité — that all-important word. Perhaps Hollande’s hawkishness is just the latest development in la mission civilisatrice. Ever since the founding of the first Republic, the French, and particularly the French left, have felt it their duty to spread progressive values across the world. They have, if you like, been neoconservatives avant la lettre.

Dominique de Villepin, the former prime minister, complained recently that his country had contracted ‘le virus néoconservateur’. ‘La guerre ce n’est pas la France,’ he said, somewhat grandly. He should have acknowledged that the urge to hasten global democratic revolution, by force when necessary, was already in France’s DNA.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in