The death of painting has been so often foretold — almost as frequently as its renaissance — that any such prediction today is nothing short of foolhardy. Of course, painting is alive and well and living in London, but you wouldn’t know that from the current exhibition of five artists at Tate Millbank. (By the way, this is a paying display, the regular admission fee being £10. Not surprisingly, it was deserted when I visited. This sort of show, to do its job properly and communicate to the public at large, should be free.) According to the press release, each of the five artists ‘has adopted an approach to painting that both exploits and subverts its conventions’. I wish. The exhibition is dull with obviousness and an almost total lack of real painterly experimentation.

It begins with Tomma Abts, born in 1967 and a past winner of the Turner Prize, if that is supposed to be any mark of distinction. She contributes small, tasteful sotto voce paintings of mostly geometric and rather stagey pattern-making, shown together with one sheet of patinated bronze. (Is this really supposed to be a painting? Could try harder, surely.) Nothing startlingly original here — it’s the sort of thing that’s been done for decades by English and American artists (one thinks of Sol LeWitt and Prunella Clough) with rather more élan. In the second room is Simon Ling (born 1968), the artist here most obviously involved with the stuff of paint. He depicts odd corners of East London — fragments of shop fronts and façades — and has a penchant for crazy orange lighting, which could signal late-afternoon sunlight or a touch of Armageddon. They’re gauche and not particularly inspiring pictures (I’d rather look at the nonagenarian Anthony Eyton’s spirited portrayals of Spitalfields), but at least Ling is using paint with a certain vividness and vibrancy.

The third room is given over to Lucy McKenzie (born 1977), who is keen on craft skills — in particular, trompe l’oeil and marbling. In her room, there’s a large quasi-architectural structure covered in canvas painted to look like marble, while around the walls are a number of highly accurate renditions of documents on pinboards. This kind of trompe l’oeil painting has always been useful for murals and theatre design, and has occasionally been fashionable in painting in the last century or so (there used to be a fine example hanging in Nottingham Castle dating from 1965), but here is scarcely more than a demonstration of technical virtuosity. The effect is more interior décor than painting, and unfortunately the response is, so what?

Catherine Story (born 1968) fills the fourth room with paintings of semi-sculptural figures that seem remarkably akin to the work Alexander Guy (born 1962) was producing 20 years ago. There’s some nice drawing to be seen, but the overall effect is distinctly underwhelming. And the final room is given to Gillian Carnegie (born 1971), whose wooden drawing (that poor cat!), repellent paint surfaces (‘Section’ is particularly horrible) and subjects drained of all juice and joy combine to sap the will to live. What can be said for this bunch of artists? Well, I suppose the mere fact that they are painting, rather than mucking about with film, photography, installation or performance. I just wish they were doing it with a little more verve and originality. Ultimately, it’s the curators who are to blame for selecting such a dreary show.

In fact, it was much more interesting to see a pair of anniversary paintings hung at the top of the Manton Entrance staircase, to celebrate, respectively, Henry Mundy’s 95th birthday and John McLean’s 75th. Both are abstracts and both have much more to offer, in their different ways, than the whole Painting Now show. McLean is no stranger to this column, a witty colourist and subtle formalist, but Mundy has become something of a legend through his lengthy absence from the art scene. Although very highly regarded by fellow practitioners and discerning commentators (the late David Sylvester was an admirer), his work hasn’t been seen much since the 1980s, save for the occasional painting in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. Mundy is still working, but has destroyed much of his output. I hope some enterprising commercial gallery or museum curator will see fit to bring his inventive and original paintings back to public attention. From the little I’ve seen, it would definitely be worthwhile.

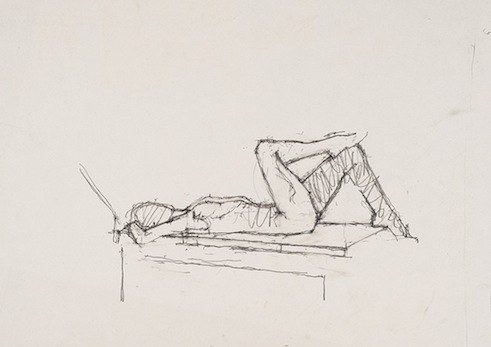

The Euan Uglow show at Marlborough Fine Art concentrates on his drawings but includes among the serried ranks of nudes (with the occasional still-life and landscape study) two oil paintings: ‘Cast’ (c.1970) and ‘Still-Life with Model Marks’ (1971–2). Both are tough paintings of difficult subjects: ‘Mask’ is a life-sized rendition of a plaster head in yellow ochre and white; ‘Still-Life with Model Marks’ is a long oval depiction of a table top on which a model had posed for another painting, entitled ‘Summer Picture’. The ‘Model Marks’ are the traces of where the nude sat on the table. Both paintings are rather austere, but in the company of the drawings they look at their lyrical best. Uglow was a rare and radical painter, and has been much misunderstood. (Too many still think of him as a simple old-fashioned realist.) The originality of his classical pictorial compositions is matched by a romantic temperament released through colour and subtle reinterpretation. It is revealing to see this high-quality selection of studies and finished drawings, not just for the rare skill on view, but also for the range of mood and pictorial invention encompassed. This is work to ponder, and I make no apologies for writing about it again, even though I did contribute an essay to the catalogue.

There’s quite a different feeling at Messum’s in its group show of work from the north of England, where an expressionist flavour pervades many of the exhibits. I much admire the boldly seamed and textured surfaces of Jake Attree’s paintings, and I’ve long been interested in the haunted clarity of Peter Brook’s isolated buildings. It’s always good to see the obsessional linearity of Percy Kelly, and Andrew Hemingway’s watercolours and pastels are intriguing, but the show’s main attraction is a powerful group of oil studies and tempera paintings by Helen Clapcott (born 1952). Clapcott paints Stockport from famous Viaduct to Carnival, via the never-ending streams of traffic pervading Tiviot Dale, and the solitary chimneys standing sentinel in the newly sanitised landscape. In her distinctive blue-grey tonalities (summoning up a smoky post-industrial atmosphere), lit with pale under-painting and touches of bright colour, Clapcott reaches towards a new identity for Stockport, a post-Lowry celebration of the northern town and its remaining mill buildings. That’s what I call painting now.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in