Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave goes directly to the heart of American slavery without any shilly-shallying — unlike The Butler, say, or even Django Unchained — and is what I call a ‘Brace Yourself’ film, as you must brace yourself for horror after horror, injustice after injustice, shackles, muzzles, whippings, rapes, hangings. You will be harrowed to within an inch of your life, as perhaps is only right, given the subject matter, but you will not wish to flee your seat. You will recoil. You will flinch. You will say to yourself, ‘Oh no, not again.’ But the story will seize you with such a visceral power you will be rooted to the spot. I know I was and I’m not easy to root. Mind everywhere, usually.

This is not like McQueen’s previous two features — Hunger, about Bobby Sands’s hunger strike in prison, and Shame, about one man’s crippling sex addiction — which came entirely from the left field. This is far more conventional, and conventionally told, with a beginning, a middle, and the end, which you will long for, not because you are bored (I wasn’t) but because you so want it to turn out OK, and for Solomon Northup to come out into the light.

It is based on Solomon’s astonishing true story, written as a memoir in 1853, and opens with him living as a free man in Saratoga Springs, New York. Played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, he is a fiddle player and appears prosperous. He has a wife he loves, two children he loves. They all live in a nice house, and the family are treated with respect and affection by the local white community. It is such a happy, elegant life you just know something is going to come along and ruin it — brace position, now! — and it does when two men lure Solomon to Washington, for what he thinks will be a lucrative short stint playing fiddle for the circus, but where he is plied with drink, and drugged, and next wakes up stripped, imprisoned, shackled, Django Re-Chained. He protests he is a free man, but there is no Life of Brian-style reprieve: ‘Oh, sorry. No servitude for you. Off you go then.’ Instead, he is beaten brutally, and then shipped south, to the plantations.

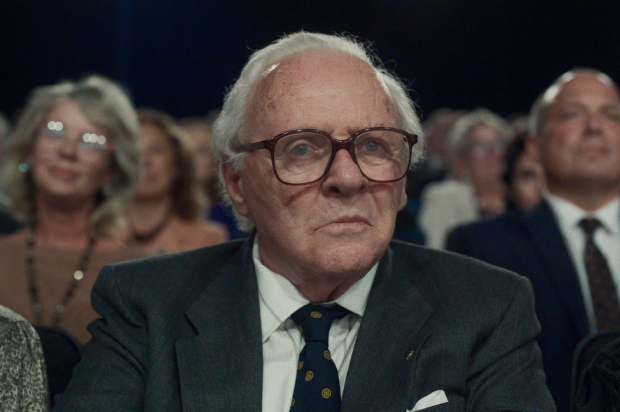

He is passed from master to master, from Benedict Cumberbatch, who is kind-ish but weak, so sticks with the prevailing order, to Mr Epps, as played by Michael Fassbender. Epps is vicious to his boots but not just vicious to his boots. He upholds the system with an iron fist but is in love with one of his slaves, Patsey (oh God, poor Patsey), can’t tolerate being in love with one of his slaves, so must destroy her physically. At some level we recognise him as a human being who is also paying a terrible price, rather than simply a monster. Slavery was a dehumanising obscenity all round. Slavery has made Mrs Epps (Sarah Paulson) vicious to her boots. We understand this, even though it is never spelled out.

Solomon has a unique perspective, being a slave who does not consider himself a slave, and the tone is coolly observational, rather than sentimental. McQueen, a British director of Nigerian descent, was a visual artist before turning to film, and carefully assembles scenes that are not just strikingly juxtaposed (the brutal against lush pastoral, for example) but also tell us more than any dialogue would: the humiliation of slaves having to gather and strip naked to wash themselves before being shipped; the pain of a mother separated from her children weeping on a stoop; Solomon near-hanging for several hours in the hot sun, just able to reach the ground with his toes, which he must keep moving like a ballerina on points, or his neck will break, as slaves go about their business around him, because death and torture are so the norm. We are shown the banality of evil close-up, and the brutality close-up — the whippings; the wounds — but the question isn’t so much: ‘do I have the stomach to look?’ More: ‘do I have the right to turn away?’

Plus, we care about Solomon, and we care what happens to him, and whether he will ever see his wife and children again. Every episode in his life is narratively tense, sometimes suffocatingly so. Will he be able to protect Patsey? Will his letter be delivered? Will the overseer kill him? The film spills with great performances — we’ll take Fassbender as read, but Lupita Nyong’o as Patsey also gets you right in the gut — but it is Ejiofor’s film. His performance is restrained, covering all the emotions — stunned bewilderment; pain; hope; but never acceptance — without ever showboating. He plays Solomon as a man fighting as much for his sanity as for his freedom, and you can’t, won’t, shouldn’t look away. So, a ‘brace yourself’ film but one that keeps you rooted to the spot. I’d buy a ticket to that.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in