Fellini’s credo ‘the visionary is the only true realist’ could also be applied to the life of Claudio Abbado, who died earlier this week in Bologna at the age of 80. It would be wrong to think of Abbado as a dreamer, for conducting at the angelic heights to which he ascended is a matter of serious thought, but he had the gift, rarer than is commonly supposed, of liberating musicians. Being liberated, they gave performances of such beauty and emotional power that those who heard them will consider their lives enriched; in many cases transformed.

Milan-born, Abbado grew up musically in Vienna, where he studied with Hans Swarowsky, and where, three decades later, he became music director of the State Opera before his appointment as the city’s director of music, a kind of honorary knighthood. By then he had also held principal posts at La Scala, the celebrated opera house in his native city, and the London Symphony Orchestra. His accession to Herbert von Karajan’s throne in Berlin came in October 1989, a month before the Wall came down, when members of the Philharmonic chose him to be that mighty orchestra’s first non-German leader.

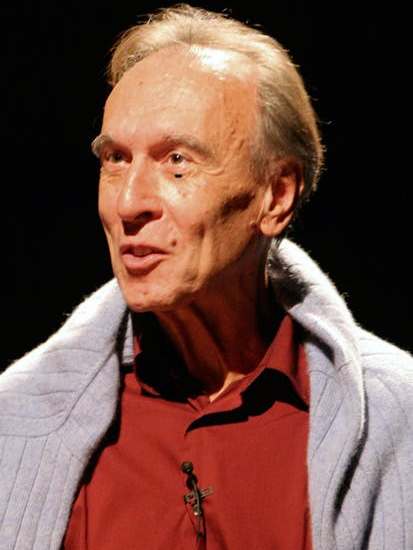

Photo: Rex Features

If Milan and Vienna caught the best of him, that wasn’t necessarily Abbado’s fault. The Karajan succession was always going to be a problem, particularly to a conductor whose approach to music-making was markedly different from Karajan’s, and he endured serious illness towards the end of his 13-year stewardship in Potsdamer Platz. He was not expected to survive the cancer that led to the loss of his stomach but, aided by the experience of conducting Tristan und Isolde with the Berliners in Japan, which he told friends had saved his life, he enjoyed a glowing final decade as conductor emeritus to the world.

In England he will be best remembered for the year-long Mahler, Vienna and the Twentieth Century festival with the LSO in 1985. By placing Mahler’s symphonies at the heart of the enterprise, Abbado was able to introduce not only Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Webern but also Zemlinsky and Schreker to audiences who might otherwise have stayed away. Nowadays the themed festival is a staple of orchestral life. In 1985 it was a major risk, not least financially, and it was greatly to Abbado’s credit that it was a resounding success.

Nobody surpassed Abbado in his mastery of Mahler’s music. Sir John Barbirolli and Leonard Bernstein, in their different ways, popularised the symphonies half a century ago, when Mahler’s music was still unfamiliar enough to be striking, and Bernard Haitink and Simon Rattle have done marvellous things. But Abbado, with his sense and sensibility, the northern Italian temperament leavened by years of immersion in the Viennese tradition, is unparalleled.

This was the Abbado that London audiences came to value above all. The 1985 festival included, on Easter Sunday, a performance of the Resurrection Symphony with Jessye Norman and the late Lucia Popp that gave everybody a glimpse of eternal life. Nine years later, at the Proms, Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, with the Berliners, was received with 54 seconds of silence. What a night that was.

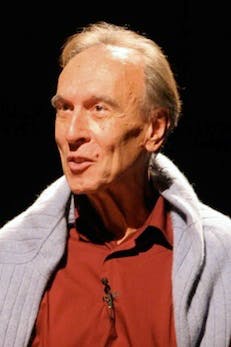

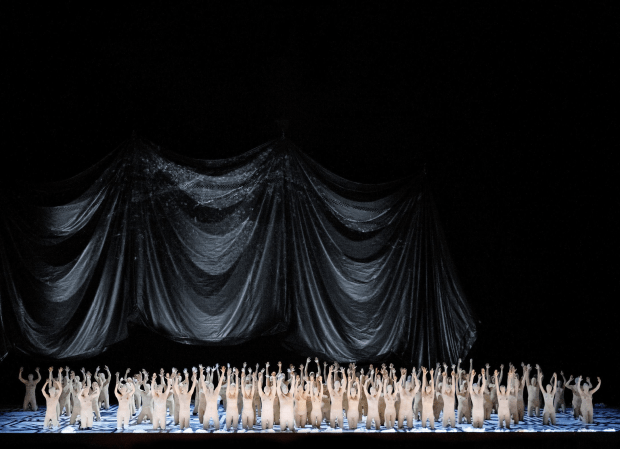

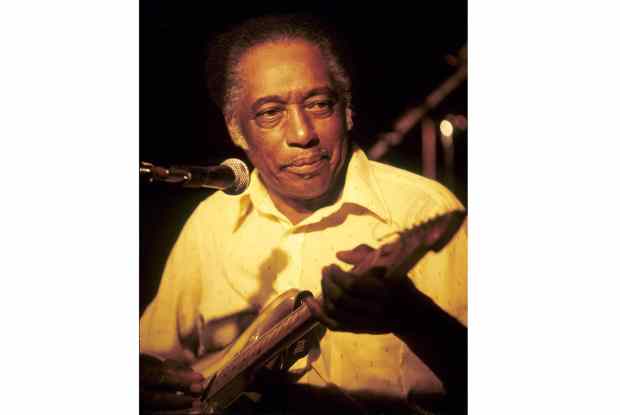

Photo: Redferns

Yet there was an even greater night to come. In 2007 Abbado returned to the Proms for one last act of communion. He brought the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, which he founded and stuffed with players from all over Europe. The symphony was Mahler’s Third, which can sound very long in some hands (no names, Mr Maazel). On that evening it seemed to be the most beautiful symphony ever composed, made all the more poignant by the knowledge that he would never return to the world’s greatest festival of music.

He wasn’t a perfect conductor. His rehearsals were often sloppy and sometimes shambolic. A deputation of LSO brass players once knocked on his door, and told him they would not be bothering with scores that night. They preferred to play from memory. ‘But you must,’ Abbado replied. ‘In that case,’ came the answer, ‘will you use a score, too?’ He did.

But that is not the man musicians have been honouring this week. This was a conductor who used his status as the leader of four of the great musical institutions in Europe to foster hope for the future in practical ways. In 1976 he helped to found the European Union Youth Orchestra. Ten years later he created the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester for young musicians who lived in countries outside the EU. Even in his declining years he established Orchestra Mozart in Bologna.

It kept him involved, and it kept him young. In his heart Abbado never grew old. His was a generous view of life, expressed through music-making which, in its supreme moments, attained the heights to which we all aspire. As visionaries can, he used his gifts to reveal our better selves.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in