James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird is set in the mid 19th century, and is based on the real life of John Brown, the one who lies a-mouldering in his grave. Recently it won a National Book Award in the USA. Brown, the Old Man, was a religious fanatic who believed that he had the nod from God to free the slaves. Early in his harum-scarum life he killed and beheaded some pro-slavery opponents with God’s sanction; like many fanatics he had a direct line to the Almighty.

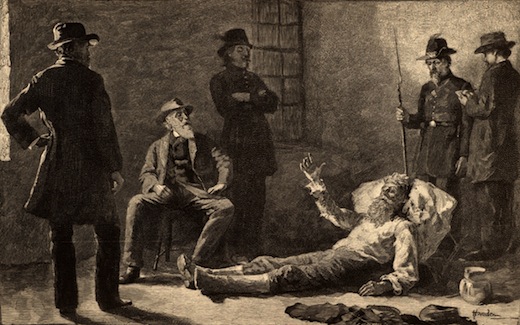

But it all ended in tragedy when, with his small band of followers, very few of whom were slaves, he took a federal government arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in West Virginia. The plan was to distribute thousands of guns to the ‘negroes’ (as McBride calls them). It was an utter disaster, which ended with Brown being arrested and hanged a few months later. Strangely enough, the legend of John Brown, who was clearly crazy, helped the abolitionist cause and is thought to have precipitated the American Civil War.

This is not the first novel about Brown. Russell Banks wrote a great book called Cloudspitter, using one of Brown’s sons, Owen, as the narrator of his father’s tragic life; in The Good Lord Bird, McBride, a musician and novelist, enlists an entirely fictional character called Onion, a boy of about 12, to tell the story. For some reason that is never explained, Onion is dressed as the daughter of a slave, and John Brown takes charge of the child, whom he regards as a talisman.

This is not the only rather arbitrary plot device. The book appears to be very random, as though the author and his editor had failed to spot that there are a troublesome number of repetitions and inconsistencies. Brown’s endless praying seems to be a comedic line that McBride has overinvested in; it becomes extremely tedious, a joke flogged to death. All Brown’s followers nod off when he quotes, endlessly and highly eccentrically, from the Bible.

McBride’s other running joke is that most of the slaves have not the slightest interest in being liberated. Even the great Frederick Douglass is nervous of going to war with Brown, who is almost invariably wrong in his strategic decisions. Onion, although occupying hundreds of pages, is never interesting or even fully realised. His language is a kind of sub-Mark Twain, ludicrously overcooked (he describes a skirmish thus: ‘The Old Man’s men was confident, shooting dead-on and putting a hurting on ’em’). Twain himself was an expert on local dialect (he had the advantage of employing a freed slave as a butler) and identifies seven in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

After the inevitable tragedy of Harper’s Ferry when most of Brown’s men are killed, or captured and subsequently hanged, Onion finds his way to Philadelphia and freedom. Unexpectedly, this final section of the book really takes wing and almost redeems what I think is a missed opportunity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £14.99. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in