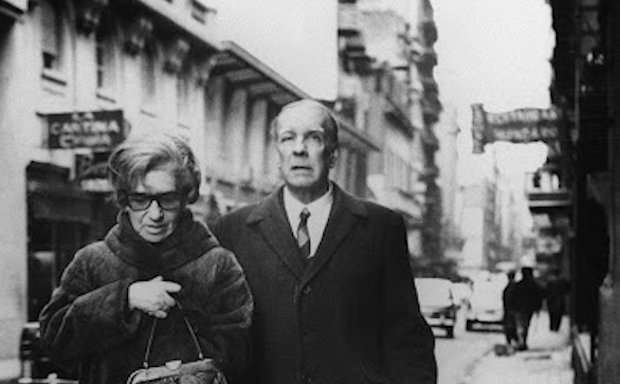

The Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector was a riddlesome and strange personality. Strikingly beautiful, with catlike green eyes, she died in Rio de Janeiro in 1977 at the age of only 57. Some said she wrote like Virginia Woolf (not necessarily a recommendation) and resembled Marlene Dietrich. She was ‘very, very sexy’, remembered a friend. Yet she needed a great many cigarettes, painkillers, anti-depressants, as well as anti-psychotics and sleeping pills to get through her final years. Lispector had great fortitude over her illness, it was said, and suffered the ravages of ovarian cancer equably and without complaint.

According to her biographer Benjamin Moser, Lispector’s was a life fraught with the shadow of past failures and past sorrows. Born in 1920 in what is now Ukraine, she emerged from the world of East European orthodox Jewry with its sidelocks, kaftans and Talmudic mysticism. Dreadfully, her mother had been gang-raped by Russian soldiers during the pogroms that followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917; her grandfather had earlier been murdered. Even by the standards of Russian anti-Semitism, the family’s was an unusually wretched story of immigration.

In the winter of 1921, harried by thieving Jew-baiters and other opportunists, the Lispectors fled their home for the New World. On arrival in northeast Brazil, they scraped a pittance through teaching and odd jobs. Clarice (born Chaya) Lispector was barely one year old when she reached Brazil; in her adult years, not surprisingly, she liked to claim the country as her spiritual home and the place where the Portuguese-language writer in her was born.

Her fiction is haunted by her family history of uprooting and exile, says Moser. The atrocities and expulsions suffered by Ukrainian Jewry after the first world war had engendered a thoroughgoing scepticism and mistrustfulness in Lispector. In coming to Brazil with her parents and two older sisters she knew she had escaped a great danger. Assimilation into Brazilian society promised an escape from the sorrows and derision of the past, so the Lispectors decided to change their names to sound less Yiddish and more Portuguese. Though Clarice would never again set foot in her native Ukraine, her writing gave covert expression to the displacement and wretchedness felt by emigrés everywhere, Moser suggests.

Among the first to ‘discover’ Lispector had been the American poet Elizabeth Bishop, who in 1963 wrote to Robert Lowell: ‘I not only like her stories very much but like her, too.’ Bishop (who had been living in Brazil since 1951) proclaimed Lispector ‘better’ even than the Argentine fabulist Jorge Luis Borges, and set about translating her into English. Since then, Lispector has been championed by, among others, Edmund White, Orhan Pamuk and Colm Tóibín. Yet she remains unknown to the general reader (I, for one, had never heard of her). Why is that? I asked my Brazilian friend Marcelo Bratke, the concert pianist, if he knew of Lispector. ‘What? Lispector is highly regarded here. She’s the most important Jewish writer since Kafka!’

Though Penguin are currently bringing out her novels as Modern Classics, Lispector has clearly not found her place in the literary canon. Her first novel, Near to the Wild Heart, published in 1943, took its title from a line in James Joyce and discomfited Brazil’s parochial literary establishment with its determinedly modernist cut and surreal, unsmiling humour. Overnight, Lispector became a succès d’estime and was idolised by the young. Intrigued by her movie-star allure, Brazilians claimed Lispector as one of their own, even if her ‘Brazilianness’ seemed to be overlaid by something strange. A part of Lispector was anchored in a cold northern soil somewhere in Russia, where the people had black bog earth on their boots and lived hard, stoical lives.

In the not-quite Brazil that Lispector embodied was a woman at once familiar and foreign to her Latin American readership. In her trademark dramatic makeup and outsize jewelry, she could easily pass for a Copacabana Beach grande dame. Lispector even wrote a Miss Manners-type newspaper column under the pseudonym Helen Palmer, which advised socialite women on which face cream to use. In the early 1960s, true to form, she embraced Rio’s new dance beat called bossa nova, whose underlying air of sadness possibly appealed to the unappeased yearning in her to return to Russia. The Brazilian diplomat-poet Vinicius de Moraes (who wrote the lyrics to Tom Jobim’s desperately sad ‘The Girl from Ipanema’) was among Lispector’s circle, as was, later, the Bahia-born songwriter Caetono Veloso.

Just as bossa nova borrowed from samba, West Coast jazz and the sparsities of Chopin, so Lispector borrowed from Joyce, Hermann Hesse, Jewish mysticism and (by her own account) Georges Simenon. These borrowings were typically Brazilian. In a now-famous book of 1928, the country’s leading modernist poet Oswald de Andrade had defined Brazilian literature as anthropophagic, or cannibalistic, ‘eating’ other forms of European and African writing. Lispector’s fiction conformed to the ideal admirably. Her 1963 masterwork, The Passion According to G.H, is brocaded with a range of literary influences from Kafka to the Bible. (Moser claims it as ‘one of the great novels of the 20th century’.)

The last two decades of Lispector’s life were riven by tragedy. Having left her foreign office husband Maury Valente in 1959, she brought up her two young sons in Rio with the help of a live-in maid. The youngest, Pedro, developed full-blown schizophrenia for which he was subjected to insulin-shock therapy. Lispector found that there were sights and sounds in the world outside that neither she nor her son could tolerate. One day in 1966 she accidently set fire to her apartment with a lit cigarette and was left with a burned, claw-like right hand for the rest of her days. When not dozing through a haze of tranquilliser pills, she found solace in translating Agatha Christie into Portuguese.

Moser, a young Texan-born author and critic, has chronicled one of the strangest literary careers of the 20th century with scholarship and sympathy. Once you pick up his spellbinding and endlessly fascinating biography, you will have to read it straight through, even if Clarice Lispector means almost nothing to you as a name.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £10.99. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in