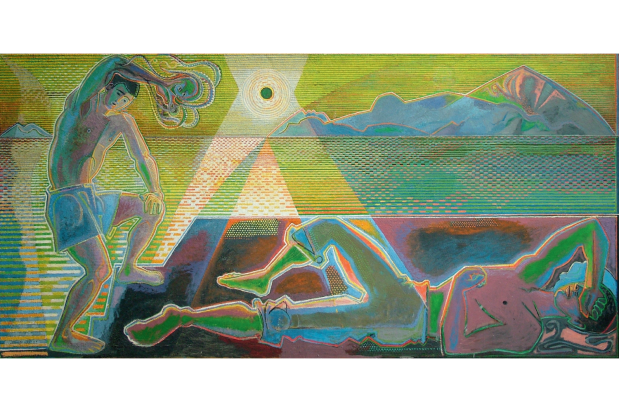

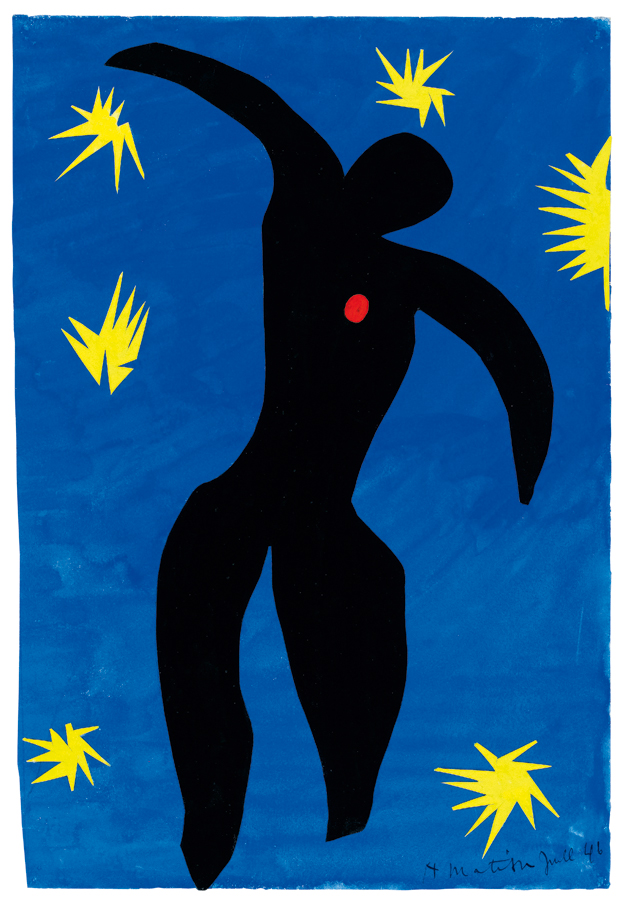

It is often said of John Craxton (1922–2009) that he knew how to live well and considered this more important than art. Perhaps there is a certain truth in this, but if he really believed it, did he have any business in being an artist? And an artist he undoubtedly was, by temperament and sensibility, as well as by the rich endowment of natural talent. Of course, letting it be known that you think life more important than art is a very good cover for that most debilitating (and paradoxically productive) of besetting fears: self-doubt. Craxton had it in large measure, and it is probably this quality that accounted both for his originality and for the painter’s block he periodically suffered. With his wide-ranging knowledge and eclectic eye, he could easily have made work that was more pastiche than personal, but his best pictures transcend the echoes of El Greco and Byzantine art, of Picasso’s Cubism and the sinuous surrealism of Miró. In fact, his finest paintings lead the viewer into a visionary universe of colour and light and bounding structures, whose taut rhythms release a feeling of euphoria in the beholder and beguile the imagination with intimations of visual splendour.

Craxton, though outwardly modest and even inclined to be self-deprecating (in wonderful contrast to the brash self-promotion of today’s art stars), nevertheless knew the worth and seriousness of his own achievement. And it is, after all, the work that lives on after the artist, whatever fond memories may all-too-briefly exist in the minds of his friends and intimates. So an exhibition — such as the one currently at the Fitzwilliam — which purports to offer a representative selection of his life’s work needs to be examined with great care by anyone interested in 20th-century British art. For we need to determine just how prominent a place Craxton should occupy in the history of the period. He never sought the public gaze — unlike his contemporary and one-time friend Lucian Freud — and as a consequence his work is not well known. Craxton’s achievement is ripe for reassessment.

Yet the Fitzwilliam’s show does not engage with such a task, instead offering a small-scale and low-key celebration, a friendly tribute rather than a rigorous examination. Having myself curated one or two museum shows in the past, I am fully aware of the constraints of cost and availability that afflict the exhibition organiser, but the real danger of any venture of this sort is that it may misrepresent by default. Those interested members of the gallery-going public, who are enthusiastic but without any specialist knowledge of the artist or the period who now make their way to the Fitzwilliam, may leave the Craxton exhibition with the belief that what they’ve seen is as good as it gets. (At least one distinguished art critic seems to have thought this, and I even heard old friends of the artist begin to wonder if their high regard for his art was somehow misplaced.) So here’s the important news: Craxton is actually quite a lot better than the sum of the Fitzwilliam show, which offers only a very partial view of this complex artist.

The gallery space accorded the exhibition does not help, being a smallish rectangular room, overfilled with pictures. The walls have been painted a pale canary yellow perhaps in mitigation, but this cannot ameliorate the sense of crowding. The size of the room is wrong for a sympathetic showing of an artist’s entire career — it’s simply too small, and inevitably diminishes the occupant. If this was the only available space, might it not have been better to mount a carefully selected exhibition of just one aspect of Craxton’s output? For instance, an in-depth focus on such an unpromising-sounding subject as the many different versions he made of tree roots in a Pembrokeshire estuary in 1943, when working with Graham Sutherland. This would have illuminated not only the crucial relationship between drawing and painting in Craxton’s method, and the range of media he employed to obtain his impressively varied effects, but also an intriguing moment of modern British Romantic art.

Drawing is a very important aspect of Craxton’s art, and I’ve known other artists who frankly prefer the open enquiry of his drawings to the sometimes overfinished statement of his paintings. There are drawings in this exhibition, but not the range that might be expected, and not all of the highest quality. Equally there aren’t enough major paintings here. One of Craxton’s great strengths was as a painter of figures in landscape, but he was also a considerable painter of pure landscape, and the finest example I’ve seen in recent years is ‘Landscape, Malevizi, Crete’ (1952), a superb balance of pattern and description. A painting of that quality and joyous, seemingly effortless execution, a perfect blending of linearity and colour, is missing from the Fitzwilliam. There again, the 1946 ‘Greek Landscape’ (also in a private collection), a large oil featuring a shepherd and a goat, would have added a further dimension to the story, linking the earlier dark English landscapes with the later sun-filled ones.

Don’t get the wrong impression — there are some excellent examples of Craxton’s work at the Fitzwilliam, and the show is well worth seeing, just so long as you don’t think this is the best he could do. Among the really fine things are ‘Scillonian Landscape’ (1945), ‘Hotel by the Sea’ (1946) and ‘Pastoral for PW’ (1948). The Forties was a great period for Craxton, of experimentation and consolidation. Even in later years, when he had trouble finishing paintings and favoured the rather unadventurous and cosmetic colours to be found in readymade tubes of tempera, he could still pull it off. He was adept at painting and drawing cats, and ‘Cretan Cats’ (2003) is a small masterpiece, with the chair-caning between the playing creatures wittily transformed into the backbone of a fish.

But with neither the breadth and sweep of a major retrospective, nor the jewel-like precision of a long-considered and finely honed focus show, this display has the feeling of a stopgap in the Fitzwilliam’s exhibition programme, over-reliant on the selection of pictures that featured in the 2011 Craxton monograph by Ian Collins. The success of that book indicates the level of interest in this artist, and it certainly whets the appetite for a wider and more scholarly approach to Craxton’s art. We need to go now below the superficial narrative of the man’s life to penetrate the meanings and boundaries of his art. I just hope that the interest in Craxton’s work will continue to grow and encourage other exhibitions to be staged, other books to be written, to offer us a more complete picture of this unusual and compelling artist.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in