If the gentle reader has any concerns that a study of land ownership might tend to the dry, they will be dispelled in the very first pages of this book by the spectacular flamboyance of its opening. There is not an economist in sight. Instead, we have the piratical figure of the Sir Humphrey Gilbert — Elizabethan seadog, soldier and mathematician, ‘openly bisexual’, and with the arresting habit of ‘decapitating his enemies after battle [and] then lining the path to his tent with their severed heads’ — returning in 1583 from the first expedition to create an English colony in North America.

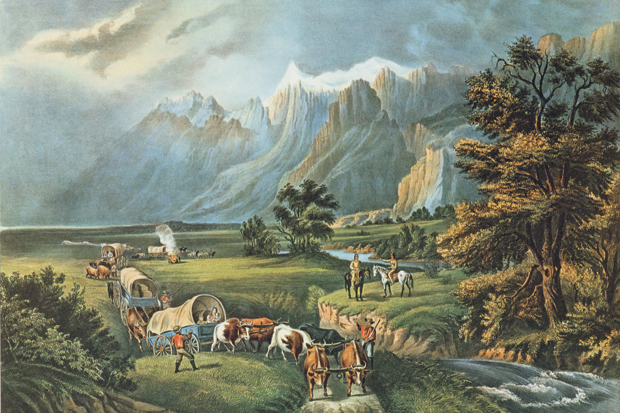

Sir Humphrey Gilbert stands proxy for a momentous historical transformation. For in Owning the Earth, Andro Linklater argues that Gilbert’s England was the first state to replace feudal principles of land ownership, founded on obligations of service and custom, with a radically new theory of landholding that asserted ‘exclusive control of the ground’: landed property was something absolutely at the disposal of the owner, to use and profit by as he saw fit.

The consequences were profound. In 17th-century Britain, this led to landowners using Parliament to assert their security of title against threats of arbitrary expropriation, especially by the Crown. In turn, the rising profitability of land, and the monetisation of the capital it represented, created the economic conditions that made possible the rise of Britain and, later, the United States as world powers. ‘Only in England and North America,’ observes Linklater, ‘did 17th-century land become capital’; and that decisive change made a ‘vital contribution …to the development of free-enterprise capitalism in both places’. If anybody needed reminding how intimately this financial system, centred on London and New York, remained tied to the ownership of land, they need look no further than the world banking crisis of 2008, with its origins in the US market for subprime mortgages and the vast Tower of Babel of derivatives and uncollateralised debt that had been constructed upon them.

To investigate how the economic system that originated in Britain and the United States came to dominate the world, Linklater sets out on an ambitious venture to traverse five centuries, and as many continents, in seven-league boots, surveying en route the feudal practices of late Ming China, the methodical subdivision of South Australia (parcelled out in the 1830s by an inspired rogue and child-abductor, Edward Gibbon Wakefield), the end of serfdom in Tsarist Russia and the collectivisation of state property in Castro’s Cuba. Linklater, who died in November last year, was a polymath — historian, economist, explorer, anthropologist, student of political theory, among a dozen other interests — and this bulging portmanteau of skills and learning, always lightly borne, informs a book that is never less than fascinating in its range, argument and erudition.

Central to Linklater’s enquiry, and unifying his kaleidoscopic array of evidence and anecdote, is what he sees as the great paradox of capitalism: how was it that a system of land ownership based on selfishness (what’s mine is mine) ultimately came to produce far higher levels of generalised prosperity than any of its collectivist — and superficially more ‘altruistic’ — rivals?

The radical selfishness at the heart of the system was apparent from the outset. In Tudor England, the assertion of exclusive title most often meant the ‘enclosure’ of lands — for the highly profitable business of grazing sheep — and the dispossession of former tenant farmers whose only claim to the land was ancient custom and usage. As thousands were reduced to destitution, critics denounced the new capitalists in language that has changed little between the time of Shakespeare and the advent of the Occupy movement: theirs was an ‘insatiable greediness of mind’, wrote one outraged Elizabethan, by which landowners had become ‘an universal wolf’.

That wolfish propensity has never quite gone away. Left unsupervised, the system’s greater wolves will not only devour the sheep, but their weaker lupine brethren as well. What muzzled, if never quite de-fanged, these wolfish tendencies was the recovery, in the course of the early 18th century, of a sense that the ownership of property carried with it moral obligations that kept the operation of greed within socially acceptable bounds. As expounded in the 1750s by Adam Smith — clearly one of Linklater’s intellectual heroes — there were ‘evidently some principles in [man] which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it’.

Of course, the market had its own self-correcting mechanisms, which Smith famously identified as ‘the invisible hand’. But the invisible hand could only function in ‘a context of concern for the general welfare’. Government’s most important role, therefore, was to provide that ‘equal and impartial administration of justice’ — a justice which entailed not only equality before the law, but also a social dimension: in particular, the avoidance of excessive disparities of wealth, whereby the richest part of society — a de facto oligarchy — can rig the functioning of the market to favour itself. And at least until the 1980s, Linklater sees European and American governments having worked within these moral constraints.

The crisis of contemporary western capitalism, Linklater argues, is that it has slipped loose of these moral moorings. When one looks for the ‘invisible hand’ today, it is likely to be in the till. The villains in this piece are Friedrich Hayek and the postwar ‘Austrian economists’. The more they and their supporters ‘insisted [that] economic liberty was equivalent to personal freedom’ — and that taxation was ipso facto a constraint on personal freedom — ‘the quicker they eroded the moral standing of the common law system, with its guarantees of individual liberty based on a reciprocal responsibility of the propertied for the unpropertied’. Sharp reductions in the marginal rates of income tax for the very rich under Thatcher and Reagan, Linklater contends, not only increased social inequality; they also produced the gargantuan increases in national debt that currently bedevil the UK and US economies.

The result of these unprecedented levels of debt (in the US currently approaching 100 per cent of GDP) has been two dangerously anti-democratic transfers of power. The international bond markets have been empowered to the point where they are now ‘a more powerful influence on government policy than the electorate’. Still more seriously, ultimate responsibility for these prodigious state debts has been transferred from the generation that incurred them onto generations yet unborn. Where lies the principle of ‘No taxation without representation’ now?

Owning the Earth brilliantly anatomises many of the ethical failings that beset the financial system of which the piratical Sir Humphrey Gilbert was an unwittingly appropriate progenitor. But the high moral tone of the book’s anti-Thatcherite critique fails to compensate for the sometimes gaping holes in the economic argument. The claim, for instance, that Thatcher’s reduction in the top rates of taxation was responsible for the escalation of the national debt wholly ignores the massive increase during the same period in the demand for, and cost of, state-supplied services (notably the NHS).

Likewise, complex historical changes that took place over centuries, such as the decline of feudalism, are often oversimplified into a single dramatic ‘turning point’. And while an international cast of political philosophers flit in and out of these pages — Aquinas, Hobbes, Locke, Suárez, and Confucius among a host of others — their cameo turns often appear imperfectly rehearsed.

No occasional lapse of detail, however, can detract from the splendour of Linklater’s achievement. In an age of pigmy specialisation, there is something heroically larger-than-life about the book’s global range and polymath accomplishment. And though Linklater did not live long enough to enjoy its plaudits, Owning the Earth is an appropriate monument to its author’s distinguished mind and ardent humanity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

John Adamson is a Fellow of Peterhouse, Cambridge, and the author of The Noble Revolt: The Overthrow of Charles I. Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.00, Tel: 08430 600033.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in