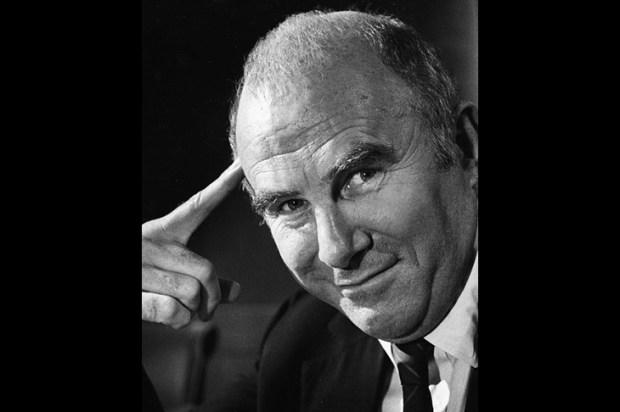

We critics seldom write our memoirs, perhaps because we skulk away our lives in dark corners, avoiding the public gaze, plying our shameful trade like streetwalkers or pushers of hard drugs. We might occasionally, in desperation, recycle our ephemera between hard covers. Edward Greenfield, the former record and music critic of the Guardian, has daringly come out, in a volume of reminiscences that carefully avoids the title memoir (about oneself) and instead labels itself as portraits (about other people). But a man is judged by the company he keeps, so we soon come back to the book’s subtitle and find ourselves reading a concealed ‘life’.

Ted Greenfield has been unusual among music critics for a number of reasons. Where most of the broadsheet reviewers of his generation (he was born in 1928) came from tolerably cultivated backgrounds, with music there or thereabouts, Ted was the grandson of a railwayman, whose own son worked his way up from solicitor’s clerk to executive officer in the Ministry of Labour.

Ted was given elocution lessons to iron out what his mother called his Essex, and he eventually got to Cambridge, became chairman of the Labour Club and a senior committee member of the Union, graduated in law and took his bar finals (though he’s evasive about the result). From there he went straight to the (still Manchester) Guardian, where he stayed, initially as a glorified filing clerk-cum-reporter, then as a Westminster lobby correspondent, and soon as record columnist and eventually, in the 1970s, the paper’s chief music critic.

The book weaves these details as a minor thread through the portraits of the title, an extended series of reminiscences of the many and various individuals whom Ted has bumped up against in a career that has been the reverse of skulking. More than most critics, he has been a networker. Not content with waiting for the records or CDs to land on his doormat, he has sallied forth with tape recorder and notepad, interviewed performers, sat through recording sessions and endured press conferences. As a reviewer over some five decades for the Gramophone, he brought to his writing an inside knowledge of the recording process and the backroom personalities that, in his view at least, put most of his fellow reviewers to shame.

At Westminster, too, he seems never to have been far from a tape recorder, and his cast of heroes (his word) and interviewees includes prime ministers, archbishops of Canterbury and disgraced MPs, as well as impresarios, media moguls, orchestral managers and a legion of composers, singers, conductors, instrumentalists and assorted recording tycoons and engineers.

Largely absent from this heavenly host, perhaps curiously, are the author’s own long-time critical colleagues. There is a teasing nod in the direction of Andrew Porter, slightly more than a nod towards the great Neville Cardus and Philip Hope-Wallace, his early seniors at the Guardian, and the rest is silence.

This might be a snub or it might be simple discretion; or perhaps it’s just that he never interviewed them. I detect, though, a defensive vein. The book opens with Greenfield’s critical credo. ‘Critics,’ he asserts, ‘are expected, even required, to be sour.’ But his aim has always been ‘to go to a concert, or put on a CD, wanting to like’. Leaving aside the fairly obvious Aunt-Sallyism of this claim (who has ever required a critic to be sour?), it might be noted that reviewing artists one has interviewed or recordings one has witnessed in the making naturally predisposes one in their favour, possibly to the point where detached (not necessarily ‘sour’) criticism becomes extremely hard.

Greenfield tends to congratulate himself on his positive influence within the musical world and on the tastes and preferences of his readers and radio listeners. And, though one might prefer him not to make it, I think the claim is fair. If not the most profound or penetrating of music critics, he has always been one of the best informed and most readable, and his enthusiasms — misplaced or not — have been infectious. His avuncular tones on the BBC’s Music magazine were, for me as a schoolboy, iconic (much more so than the grumpier ones of Julian Herbert, the programme’s presenter). A good deal of all this survives in the book, peeping out from behind its motley, more or less distinguished crew of dramatis personae.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Stephen Walsh is the author of Mussorgsky and his Circle and has been a music critic at the Times, Daily Telegraph, Financial Times and Observer. Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £14.99, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in