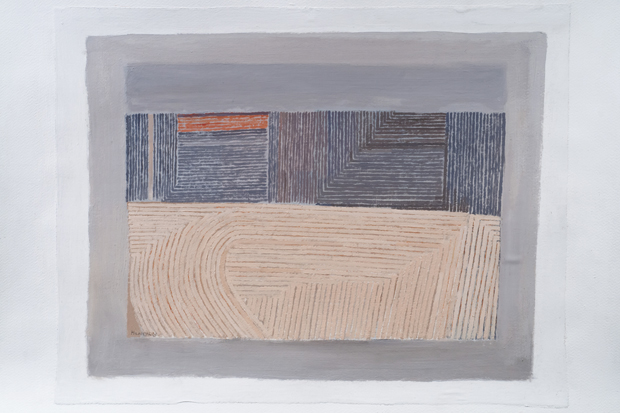

In this round-up of exhibitions in London’s commercial galleries, I feature three shows of little-known but mature contemporary British artists. There is a great deal of interesting and worthwhile art being made out there, but not enough of it comes to public attention. Most museums won’t show it, and there are only a handful of commercial gallerists who are prepared to back quality over proven popularity. In such a world, the quieter talents tend to get overlooked, so it is a particular pleasure to be able to draw your attention to the subtle small paintings of Liam Hanley (born 1933). Hanley paints in oil and draws in pencil on linen laid down on to paper. He has for many years been obsessed with a tract of land near the A10 in north Hertfordshire, and in particular with half-a-dozen huge fields that he loves to paint in mid-August when the crops have been harvested and the land ploughed and harrowed. Recently he has made of these fields a series of striated paintings, pattern-led designs, which transform the furrowed fields into more abstract arrangements of angular parallels. These delicately delineated but robust compositions capture something of the landscape while formally translating it. Hanley’s most recent paintings introduce another source of pattern: the shadows of clouds on the ploughed land, a further complication which adds to the beauty of his lines. Modest work, but of genuine achievement.

Pilar Ordovas continues to mount remarkable museum-quality shows in her Savile Row gallery. Currently you can see a small but choice selection of works by Paul Gauguin: just four pieces, all from private collections, but what a sense of originality inhabits the gallery through them. My favourite is ‘Jeune homme à la fleur’, painted in Tahiti in 1891, a portrait of a young man against a modulated blue ground with a flower behind his ear. I’d love to have seen this painting juxtaposed with one of Craigie Aitchison’s best portraits. Gauguin was a seminal influence on Aitchison, and I’ve no doubt that Craigie would have been enchanted by this depiction of a young man. We are offered, however, by way of contrast, a patinated plaster sculpture, ‘Masque de sauvage’, and two other paintings. The better of these is ‘Le toit bleu’ or ‘Ferme au Pouldu’, an earlier picture, painted in Brittany and constructed around a central area of pink, which is the farmyard. Gauguin’s great skill with colour is beautifully evident here, long driving brushstrokes alternating with briefer marks. The fourth work is a late woodland scene of magical incantation; exotic and intriguing, it doesn’t have the seemingly effortless splendour of the Brittany farm or the portrait.

At Pace London, at the back of the Royal Academy, is a very different kind of installation: four frosted-glass screens animated by immensely sophisticated displays of LED lights. These four individual works are by James Turrell (born 1943), master-manipulator of how we perceive colour and light. Turrell can make you look at the sky with new intensity and heightened awareness, and his walls of interior light have beguiled viewers for more than 30 years. His work draws upon nature, but also upon astronomy, physics, architecture and theology; it is exceptionally beautiful and thought-provoking.

On the ground floor of Pace, the gallery has been divided into three separate booths: in the middle is ‘Sojourn’ from 2006, a ‘Tall Glass’ (upright or portrait format), while the two outside works are from the ‘Wide Glass’ series, in horizontal or landscape format, entitled ‘Kermandec’ and ‘Pelée’ respectively, both new and never previously exhibited. Talking about these screens as portrait or landscape is little help in summoning them up. The best description would be as living, breathing Rothko paintings — screens of constantly evolving colour and light. The effect is mesmeric and calming, as colours mutate, fuse and fade. Some of the elisions and transformations are simply exalting, like watching a more controlled sky at sunset. Mars violet and rose madder changes to turquoise, lilac and orange, to pink, brown and green. Upstairs there’s another ‘Tall Glass’, entitled ‘Sensing Thought’ (2005), with a bench in front so that viewers may sit at ease and just watch. Hours could pass in these chambers of light…

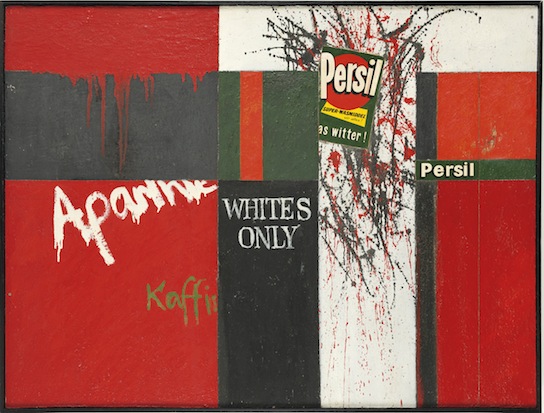

The Redfern Gallery, in association with Conor Mullan, has mounted a fascinating exhibition, which takes another look at the early work of Brian Rice (born 1936). Associated with Pop art and British abstraction, Rice lived in London from 1962 to 1978, and for many years was an active part of the contemporary scene, but then opted out of the art world and bought a 50-acre farm in West Dorset.

For a time he was preoccupied with sheep, building projects and archaeology, but he gradually began to exhibit again. However, his self-rustication has resulted in him rather slipping off the radar, and his current re-emergence is not only well timed but also comes with a real sense of discovery. The show is exciting and juxtaposes geometrical designs (stripes and targets) with more organic landscape abstracts. My personal favourites are the powerful blocky landscapes from 1959–61, but the show as a whole looks remarkably fresh.

It is accompanied by a substantial catalogue with text by Ian Massey and a foreword by Rice’s friend and contemporary, Derek Boshier the Pop artist. In addition, a catalogue raisonné of Rice’s prints has just been published, detailing 60 years of work in handsome paperback format (Sansom & Co., £40). Brian Rice is a skilled and experimental printmaker, investigating all manner of (mostly abstract) imagery, from Japanese symbols to African textiles, via ancient curvilinear decoration, mazes and the archaeological traces of Dorset, where he still lives. Some of his best recent works are simple combinations of dots, rectangles and plangent colour: his eye for pictorial design is clearly undiminished in acuity.

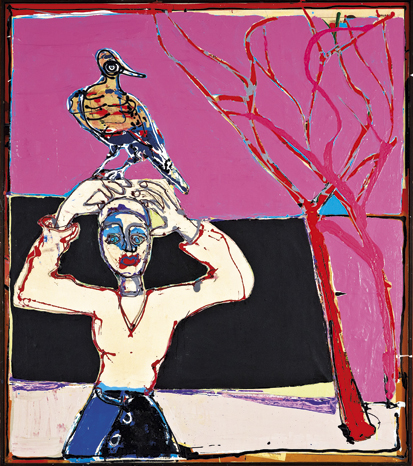

John Kiki (born 1943) is another artist not as well known as he deserves to be, though among artists he is celebrated: Frank Auerbach, for instance, is a supporter. Kiki hails originally from Cyprus, and although he paints the classical myths, he reckons his upbringing in Great Yarmouth (where he still lives) has been more important for his art than the Mediterranean. The slightly louche vigour of the seaside town, the razzle-dazzle of funfair and the lights of seafront and piers have all fed into Kiki’s imagery.

He paints non-naturalistically, but employs recognisable figures in the flattened spaces of his vibrant compositions. Zeus and Europa, Leda and the Swan feature in modern (un)dress, along with Mickey Mouse, unspecified lovers and dog-walkers. Kiki draws with a wonderfully liquid line in acrylic paint, paring down the description to the most telling details, and increasing the intensity of the colour contrasts and surface textures. He likes to reprise great masterpieces of the past, particularly by El Greco, Velázquez and Picasso. His version of El Greco’s ‘Burial of Count Orgaz’ is one of the most impressive paintings in a highly concentrated and passionate exhibition.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in