Listen

‘Money has won,’ Martin Amis said this week, promoting his BBC4 programme Martin Amis’s England on telly this Sunday. The class gulf has disappeared, he said, replaced by a money society.

It’s a little more complicated than that. Class differences are still stonkingly obvious in this country, whenever you open your mouth or put your clothes on in the morning. But it’s never been easier, or quicker, to hurtle up the class ladder by the deft application of huge amounts of money.

Britain may still ostensibly be a monarchy, but what it really is is an oligopoly, run by the oligoi — Ancient Greek for the few. And increasingly the oligoi — and not just the Russian oligarchs — are very, very rich indeed.

The old elite, including the monarchy and the political parties, aren’t quite broke yet, but they are desperate to shore up their assets. And the new billionaires on the block have never had so much money to give away, or so many reasons to give it away in return for power, preferment and a seat at the top table.

If you want to eat above the salt, it’s just a question of getting your chequebook out. This week, the Telegraph revealed that the bargain basement starting price is £150,000. That will buy you an EU passport in Bulgaria, and all the rights to work and residency across the EU that come with it.

But money can take you much higher up the batting order than that. Last week, Prince Andrew hosted, and paid for, a dinner at Buckingham Palace for Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, and 20 senior bankers from HSBC, JP Morgan, Barclays and the financial services group ICAP. Last autumn, he hosted another dinner for the American bank JP Morgan at Buckingham Palace. Among the guests was the patron saint of freeloaders, Tony Blair.

In theory, the evening made no profit. The palace said that JP Morgan paid an undisclosed fee for food, drink and the venue. And the bank said that it made charitable donations to the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the English National Ballet, who entertained the guests.

But, even if no one made any money, it’s hard to avoid the glaring impression that big money now opens the grandest of doors. Corporate hospitality is fast becoming a gilt-edged cottage industry for the monarchy. Last summer, Prince Andrew — again — hosted a mega-thrash at Windsor Castle for internet entrepreneurs.

But it’s not just Prince Andrew who’s at it. His older brother will be delighted to break bread with you if your bank account is bulging at the seams. Last November, an Indian private equity tycoon, Cyrus Vandrevala, and his wife, Priya, donated half a million pounds to pay for Prince Charles’s 65th birthday party at Buckingham Palace. It all sounds very cosy: Cyrus got to sit next to Camilla; Priya sat next to Charles.

Pay enough money and the thickest of embossed invitations — with that loveliest of franking marks on the envelope, EIIR — will come fluttering through your letterbox. In 2011, it emerged that the huge Spanish tiling company Porcelanosa paid for a significant proportion of the costs of a dinner at Buckingham Palace hosted by Prince Charles. And hey presto, the head of Porcelanosa, Manuel Colonques, and his wife, Delfina, were promptly asked to Prince William’s wedding.

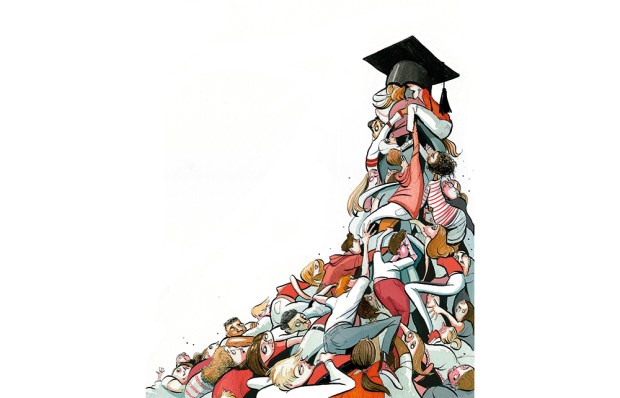

But you can get much more than invitations if you spend the money in the right places. Political parties — whose membership has plummeted to 2 per cent of the population — are mustard keen on your donations. Particularly if, like the Lib Dems, your poll rating has halved in recent years.

You’d have thought any sensible billionaire would have better things to spend his hard-earned millions on than the Lib Dems. A gin palace, a chilled bottle of Krug, a tepid glass of Pinot Grigio… Surely they deliver more pleasure than a low-temperature evening with Nick Clegg’s stunningly dreary inner circle?

But for all their Mogadon tendencies and their collapsing ratings, the Lib Dems do have one last shot in their locker: they maintain a disproportionate hold on modern political power.

The founder of the UK franchise of Domino’s Pizza, Rumi Verjee, certainly found the Lib Dems engaging enough to donate £770,000 to the party. And last September he became Baron Verjee of Portobello.

There’s no suggestion of any impropriety on Lord Verjee’s part or of any connection between the donation and the peerage. But the sandal-wearing, tofu-chewing Lib Dems do seem surpassingly keen on donning a dinner jacket and shaking down other squillionaires, with a blind eye to the possible source of the money. They took £2.4 million from Michael Brown, the fraudster financier, to fight the 2005 election. Their blind eyes must have been on stalks — that was ten times the biggest donation they’d ever received before from any individual.

Last month, the Indian arms dealer Sudhir Choudhrie and his son, Bhanu, who both deny any wrongdoing, were arrested by the Serious Fraud Office in connection with alleged bribery by Rolls Royce. The Choudhrie family have given more than £1 million to the Lib Dems and in return Sudhir Choudhrie has been entertained — if that’s the right word — by Nick Clegg at Chevening, his grace-and-favour country house in Kent. The Lib Dems have also put forward his name for a peerage in the past.

There’s no suggestion of any direct illegal connection between donations and peerages. If you want that sort of thing, you have to go back to the days when the Liberals were in real power under Lloyd George. It was Lloyd George’s honours broker, Maundy Gregory, who flogged knighthoods for £10,000 and baronetcies for £40,000.

But at least that was considered enough of a scandal to lead to a change in the law and the passing of the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act of 1925.

These days, it is openly acknowledged that money is the oil that greases the wheels of power and sends you flying to the top of the tree. And if you’ve been caught up in something unwholesome in your home country, don’t worry: British doors are flung open wide to anyone who can afford the trifling price of non-dom status.

Somerset Maugham called the French Riviera a sunny place for shady people. Well, Britain has become a shady place for shady people, as long as they’re prepared to stump up the entrance fee. Give enough of the folding stuff away and all sins are forgiven. And you don’t have to be a foreigner to rehabilitate your reputation through the all-redeeming power of money. Gerald Ronson, jailed for his part in the Guinness share-trading scandal, was given a CBE in 2012 for his charitable donations.

In the film Wall Street, Gordon Gekko didn’t quite say ‘Greed is good.’ What he actually said was ‘Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.’ And his words are spot on in modern Britain if, instead of ‘greed’, you substitute the better words, ‘Making shedloads of money and giving a proportion of it away.’ Who cares what you do with your right hand as long as your left hand donates some of the proceeds to a good cause? These days, Gordon Gekko would be savvy enough to build up the Gekko Charitable Foundation to slip a cosy veneer over the money-making machine whirring away behind the facade.

Lots of dodgy billionaires do it these days: start a charity ball; rescue a crumbling building; subsidise an ailing sport — whatever takes your fancy and sounds nice and selfless, as long as it’s suitably prominent. Nothing washes whiter than a big charitable donation.

Of course, some zillionaires are just straightforwardly philanthropic. Bill Gates and Warren Buffett must be praised for their massive charitable donations, but should they really become some of the most revered people alive as a result? In a YouGov poll this January, Gates was voted the most admired person on the planet, and Warren Buffett the eighth most admired. Barack Obama came second; Vladimir Putin third, although his ratings might have slumped a little in recent weeks. Poor Pope Francis came fourth, and the Dalai Lama 13th.

Good for Gates and Buffett for giving away so much. But they still remain rich beyond the dreams of avarice. Is an extremely rich man who gives away a chunk of his money really that much more admirable than a poor man who gives away a larger proportion of his?

Big money has a dazzling, hypnotic effect all its own, with a particularly magical power over other rich men. At a 2011 concert in Seattle, that skilled tax avoider Bono said a special thank you to Bill and Melinda Gates. ‘Thanks for your passion, your brain power and your cash, actually,’ Bono said.

The pop star was joking, but his choice of words was serendipitous. Without the booster effect of big cash, real virtues — like intelligence, selflessness and altruism — are starved of attention.

All praise, too, to the hedge-funder Arpad Busson, whose ARK charity has raised millions of pounds for health, education and child protection across the world. It’s not his fault that a good way of raising money these days is to have grand parties at Kensington Palace with the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, drawing in the hedge-fund kings, who’ll cheerfully spend £5,000 on raffle tickets and and a quarter of a million for a weekend at Blenheim Palace.

But it’s another example of how big money tears down barriers — and how quiet, unadvertised acts of charity seem increasingly dated. St Francis of Assisi wouldn’t have got very far these days. The silly friar gave away his father’s entire silk fortune. What sort of public platform would that have given him now?

‘Pecunia non olet’ — ‘Money doesn’t smell’ — the Emperor Vespasian said of the urine tax he levied from the produce of public urinals, sold on to Roman tanners and launderers. It’s true. Any money spent in a good cause is hard to attack; although I’m not sure whether the Liberal Democrats are ever the best of causes.

But that doesn’t mean having lots of money is in and of itself a shining, laudable virtue that opens any door in the land. Money may not smell bad, but it shouldn’t smell as sweet as it does in modern Britain.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in