The traditional story told about the first world war is that it changed everything: that it was the end of the old world and the beginning of the modern age, and that art and poetry could never be the same again. So it is refreshing to find, not far into Lance Sieveking’s amiable and haphazard memoirs, the claim that ‘I didn’t realise it at the time, but in 1919 I was a comparative rarity: a complete young man, a man with two arms, two legs, two lungs, two eyes.’ He had fought in the war, and came home unscathed, and that was that. Airborne: Scenes from the Life of Lance Sieveking is a slightly otherworldly book: a collection of agreeable stories drawn from a colourful life, all told with good humour and very little fuss. It reads like a document from a lost time.

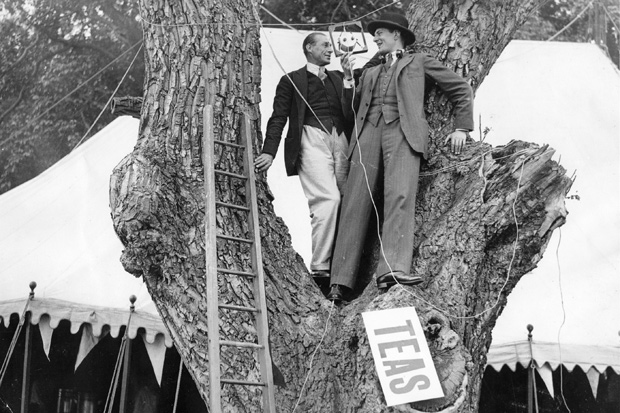

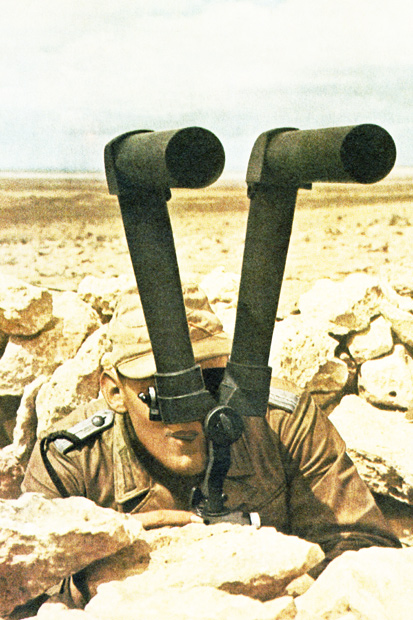

Sieveking was born in 1896, into a Victorian family of suffragettes, worthy causes and cello lessons, and grew up on the south coast of England. He briefly joined the Artists’ Rifles during the first world war, but when it became clear he was too tall for the trenches — he was six foot six — he transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service. He learned to fly in an open plane, which he describes as ‘a thing like a winged bicycle made of wood, linen and piano wire’, and later was the pilot on Handley Pages on bombing runs in Belgium. In October 1917 he crashed and was captured by a German sergeant with a comic moustache. He spent the rest of the war in a German prison camp, where he wrote nonsense verse and staged plays to entertain the other prisoners.

He then joined the BBC, in its very early days, and there produced avant-garde radio programmes, including his most famous work, the ambitious Kaleidoscope (1928). He describes this as ‘A rhythm representing a life from cradle to grave’, and it was composed of three orchestras, a huge range of sound effects, and performers in sevenradio studios simultaneously. John Gielgud performed as ‘the voice of Good’, and Sieveking conducted the live broadcast.

Modernist radio is a less well-known field of modernist art, in part because — like ballet — very little of a radio programme survives after it has been aired, and it seems not to have occurred to anyone to make a recording. But it is a recognisable part of the larger movement: Sieveking’s radio production shares with modernist poetry and painting the technique of montage in order to capture the rush of subjective experience, as well as a deliberate interest in the artistic possibilities of confusion.

Sieveking had a long — and very influential — career at the BBC. He developed the techniques for radio features still used by the BBC today, and invented the style of sports commentary. He also produced the first television play, an adaptation of Pirandello’s The Man with the Flower in his Mouth, which aired in July 1930. After his retirement from radio, he wrote novels influenced by H.G. Wells, as well as short stories and thrillers. A particular success was his crime thriller A Tomb with a View (1950), which is perhaps worth reading for the title alone. He gets married and then divorced several times, always with a minimum of self-reflection.

His memoirs have been collected and edited by his son, and appear with an introduction by an academic, making claims for Sieveking’s importance: ‘He was a full-blooded participant in the cultural life of the 20th century.’ This may well be true, but the book at heart is the portrait of an old-fashioned English eccentric. Sieveking writes like an after-dinner raconteur, telling stories about running away from lions in East Africa, and beginning with lines such as, ‘One warm night in June 1917 I became the man who nearly killed the Kaiser.’ In his preface, Paul Sieveking notes what he gently refers to as his father’s ‘imperfect recall’ and ‘impressionistic approach to history’, which might be another way of saying: don’t take this too seriously.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Airborne (limited edition of 250 copies) can be bought by Paypal at www.strangeattractor.co.uk – or post a cheque, made out to Paul Sieveking, to Strange Attractor Press, BM SAP, London WC1 3XX.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in