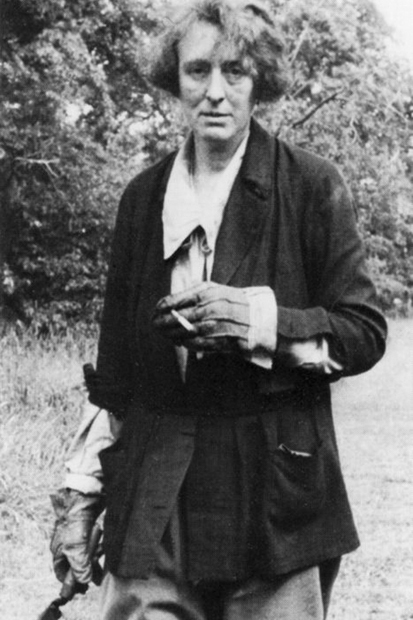

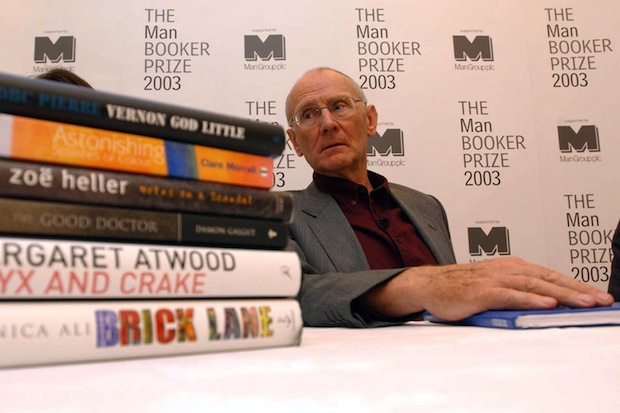

Anyone brought up as I was in a Daily Express household in the 1950s — there were approaching 11 million of us readers — knew the writings of Chapman Pincher. His frequent scoops, mostly defence- or intelligence-related, sometimes political, scientific or medical, were unusually well-sourced and headline-grabbing. Now, aged 100, he has written his autobiography. He writes as directly and vividly as ever.

After an enjoyable Darlington childhood, he progressed through grammar school to King’s College, London, where he won prizes for zoology and botany and published research papers as an undergraduate. He became a teacher and got into freelance journalism via the Farmer & Stockbreeder. A scientific future beckoned but the second world war intervened and he found himself in the army as a weapons specialist. Knowledge and contacts gained there enabled him to freelance incognito for the Express while still serving, taking a permanent job the day after he was demobbed.

He retired from Fleet Street in 1979, becoming one of the outstanding journalists of the second half of the century. He was successful partly because he was atypical: a non-smoker, never in debt (not even a mortgage), never drunk, a lone wolf who avoided El Vino’s and bibulous colleagues on the grounds that his time was better spent cultivating contacts. In this he was as assiduous as he was ruthless in exploiting and careful in protecting them. Refused offers of editorial advancement, he methodically preserved everything he wrote and now has 38 volumes of cuttings at home.

He is no kiss-and-tell merchant, however, and is discreet about his private life — although he does remark, while informing us that his second wife left him, that ‘any man who makes merry with the lower half of my wife can also have the half that eats.’ His third marriage has obviously been a long-lasting success.

He attributes much of his professional success to luck but, like many of the lucky, he clearly did much to create his own. A workaholic whose motto was ‘Who knows wins’. he was brilliant at getting people to talk to him, never pumping them hard, never taking a written note but — blessed with a good memory — recording everything afterwards.

He specialised in the great and the good, from royalty downwards, and made many of his best contacts through his twin passions, shooting and fishing. Almost everyone, by his account, became his friend, risking careers by confiding in him. Motives were mixed — to damage opponents, to influence policy, to take the sting out of bad news, but often (more with men than women) because of what he calls ‘the peacock factor’ — showing off about being in the know. His most cherished professional compliment came from his political opposite, the left-wing historian E.P. Thompson, who described him as ‘a public urinal where ministers and officials queued up to leak’.

In terms of identifying and exploiting sources, then getting the story — always his prime motivation — he would have made a superb intelligence officer (indeed, the Russians once tried to recruit him as an agent, but he was too robustly patriotic to fall for that). This makes it all the more ironic that his professional scepticism should have deserted him when, in later years, his collaboration with the renegade former MI5 officer Peter Wright brought him under the spell of a great untruth — that Roger Hollis, former Director General of MI5, was a Soviet agent. It’s true that Hollis was investigated, at the instigation of a cabal of MI5 fantasists including Wright himself, but he was cleared, rightly. Pincher’s case against him here and in earlier books is a farrago of could-haves, may-haves, elisions and inaccuracies. He dismisses as ‘fatuous’ the account by Christopher Andrew in his authorised history of MI5, despite the fact that Andrew — unlike Pincher — has actually read the files.

He quotes Wright’s sister as calling her brother a compulsive liar and vindictive mischief-maker, yet concludes his Wright-inspired account with, ‘Though my investigations will continue, in legal terms, I rest my case. The facts speak for themselves.’ But they don’t, not when half aren’t facts at all and the rest are ventriloquised into the service of a conspiracist fantasy.

The sad result of this obsession is that it overshadows Pincher’s lifelong achievement as a great investigative journalist who revealed many truths that didn’t need to be hidden, or should not have been, and who occasionally suppressed some in his country’s interest. After a century of observation, he is surely right to believe that the secret to a happy life is not, as Cicero urged, freedom from care, but a sense of purpose. Getting the story was his, and — mostly — he got it right. I wish him luck with the next hundred.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.00, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in