There is a story told of Gough Whitlam as Prime Minister speaking with his Treasurer, Bill Hayden. It is late 1975 and Hayden has just been informed by the Treasury, during Question Time in the House of Representatives, that Australia has lost its AAA credit rating. They meet behind the Speaker’s Chair immediately after Question Time. Hayden passes on the bad news: ‘Leader, I have just been advised that the ratings agencies in New York have downgraded Australia from a AAA credit rating’. ‘Comrade,’ replies Whitlam. ‘This is a disaster. Now tell me, what is a AAA credit rating?’

This tale, probably apocryphal, says a great deal about the Whitlam government. For all the landmark achievements in matters of politics and culture, not to mention the social structure of the country, the Labor governments of 1972-1974 and 1974-1975 never really mastered economic policy, until close to the very end.

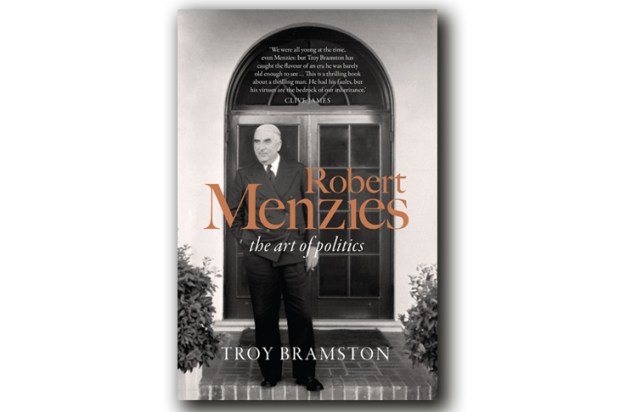

Troy Bramston is a columnist with the Australian and an emerging Labor historian. The disclaimer here is that I contributed a chapter to his earlier book, The Wran Era. His other achievements include Looking for the Light on the Hill and as co-editor of the Hawke Government: A Critical Retrospective. He is accomplished and grows in reputation.

Bramston’s new effort, The Whitlam Legacy, ought to be read consistent with the other milestone books of the period: Graham Freudenberg’s A Certain Grandeur and Whitlam’s own The Whitlam Government 1972-1975, balanced with Alan Reid’s The Whitlam Venture.

E.G. Whitlam was both a moderniser and reformer, leading the ALP out of an electoral wilderness in which it had wandered since the defeat of the Chifley Labor government in 1949. He was an intellectual and elevated in his approach. But economics was not an abiding interest or strength.

It is worth nothing that the Hawke and Keating Labor governments (1983-1996) are impossible to measure and appreciate without understanding the Whitlam experience. Federal Labor in those later years regarded the Whitlam period as having been a reconnaissance in force. Between 1972 and 1975 there was much achievement but there were also many failures. In essence, Gough’s legacy is to be found not only in his success but also as a cautionary tale as to how future Labor governments ought not to behave.

Like prophets delivered from the desert of opposition, the Whitlam government pursued politics at a warp speed. Foolishly, it never abided by Neville Wran’s famous dictum: ‘The first duty of any Labor government is to stay there.’

But E.G. Whitlam certainly changed the manner in which Australians view the national government, acknowledging that Canberra could and should play a greater part in the economic, social and cultural life of the country in areas such as universal health care, tertiary education; the arts or the cities. Significantly, the Australian debate now is to whether or not that national role has become excessive.

But the global oil crunch of 1973 resulted in a recession that took the Labor government by surprise. High inflation and growing unemployment came to dominate the Australian economic experience in 1974 and 1975. For a time, it seemed as if the Whitlam government had actually lost control of the nation’s economic policy levers, especially during the farcical pantomime of Dr Jim Cairns’s period as Treasurer.

Bramston has assembled a formidable array of talent as narrators. Bob Carr confesses to having been a teenage Whitlamite and gives an illuminating view of ALP politics. The Labor party that Carr joined in 1963 was led by Arthur Calwell and existed in a narrow and barren landscape. It lived in past glories. As he puts it:

So there lived a strong pride in the great Labor governments of 1941 to 1949. But it was one that needed to be revived by some suggestion of a great nation-building Labor government in the future. And Whitlam had to lead that government. The alternatives to Whitlam were derisory, a cruel joke on many aspirations to see a revived reformist ALP providing a long-term government.

Gerard Henderson writes well on the opposition under Billy Snedden and Malcolm Fraser, asserting accurately that the conservative coalition was simply not prepared for opposition. Nick Cater has an intriguing chapter on the 1972 Labor campaign, centring on the slogan, ‘It’s time’. However, the best chapter and most comprehensive assessment of the Whitlam government is provided by Paul Kelly. Whitlam’s legislative achievements and strong record in foreign policy, will always be eclipsed by failure in economic strategy and The Dismissal. Whitlam is seen in two ways by Australian history: ‘…Whitlam, therefore, has a hybrid legacy — as hero and villain.’

Kelly and Bramston have a chapter on the Dismissal itself, which really does shed new light on the personalities involved, especially Sir John Kerr and Sir Garfield Barwick. James McClelland always maintained that Kerr was embarrassed by his humble origins. If any proof were needed of Kerr seeking approval from the legal and political Establishment, it is to be found here.

The book is marred by minor errors, such as the seat of Fremantle being misspelt. But it does justice to the Whitlam experiment, highlighting political and legislative success, while never ignoring failure or folly.

The reforming Hawke and Keating governments could not have been as resilient or as purposeful without the lessons of 1972 to 1975. E.G. Whitlam changed national government both in reality and perception. Troy Bramston has done an admirable job in seeking to bring many threads in this political tapestry together in a highly readable, engaging and honest way.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Stephen Loosley is a former ALP national president and senator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in