Comedians always like to claim that they started making jokes after childhoods made harsh by poverty; that at a formative age they were tormented by appalling cruelty and neglect. Griff Rhys Jones had to leave Wales at the age of six days, for instance. Nevertheless, the Chaplin family could afford a maid in Kennington. The Leeds of Alan Bennett and the Morecambe of Victoria Wood always sound cosy — as does the Hadley Wood of Eric Morecambe; and there was not much wrong with Barry Humphries’s salubrious Melbourne, though I concede it has been knocked flat by ‘developers’ since. But with Andrew Sachs the horrors were very real. Aged eight, ‘I stood open-mouthed as a number of men, wielding wooden clubs, shattered the front of a shoe shop. It was 9 November 1938. Kristallnacht.’

Sachs was born in Berlin, with a Jewish father and a Catholic mother. Dr Hans Sachs was a decorated Great War veteran, ‘of solid-gold Prussian ancestry’. This now counted for nothing. He was a distinguished lawyer, but work dried up: ‘Long-standing clients found it necessary to take their business elsewhere.’ On top of which, a 20 per cent tax was levied on Jewish property. Sachs’s mother’s jewellery was confiscated. The family was humiliatingly thrown out of their favourite restaurant and harassed generally: ‘Jewish patronage was no longer welcome.’ Insult was added to injury when a ‘collective fine of one billion marks was levied on Jews to pay for the damage’ caused by all the Nazi vandalism.

The Sachs’s were fortunate to have the wherewithal to escape — Jews wanting to leave the Reich had to purchase expensive permits and exit visas. Hans ‘packed his bags and saved his life’, and the rest of the family followed shortly afterwards, abandoning their apartment and heirloom furniture. Bourgeois comfort was exchanged for refugee status in Hatch End.

Andrew vividly recalls his first sight of the London populace — characters straight out of Hogarth or Cruikshank engravings, ‘displaying unsightly blemishes and bandy legs, embarrassing acne, cold sores, moles, boils, crusty warts and false teeth that clattered’. The family ended up in the damp basement of a house in Oppidans Road, owned by the anthropologist Malinowski, which was later ‘crushed to pieces by a V2 rocket’.

Sachs Sr was interned for the duration on the Isle of Man. ‘We were told that the British wanted to make sure there were no Nazi infiltrators.’ When he was released, he got stomach cancer and died. Sachs Jr did his best to blend in and learn a new language: luvaduck, cor blimey, wotcher mate and shitabrick. His first confident English sentence was, ‘We got a canary, you know. Lovely little fucker.’

As an assimilated cockney, Andrew Sachs was given work as an extra in Ealing comedies. He toured Wales for the Arts Council. In Manchester he was directed in a flop by a pompous Noël Coward. In truth, he says very little about his career as an actor: nothing about how he started or what made him choose the profession in the first place. Nevertheless, he does mention in passing that ‘there are times when you have to be careful about what you reveal of yourself, in order to fit in’ — so it could be argued that as a terrified Jewish immigrant, on the run from Nazi persecution, a world of disguise and masquerade was also a world of concealment. Pretending to be someone else with conviction is what made Sachs feel safe — and such was his facility that in an average month he’d appear in 17 different radio productions at the BBC.

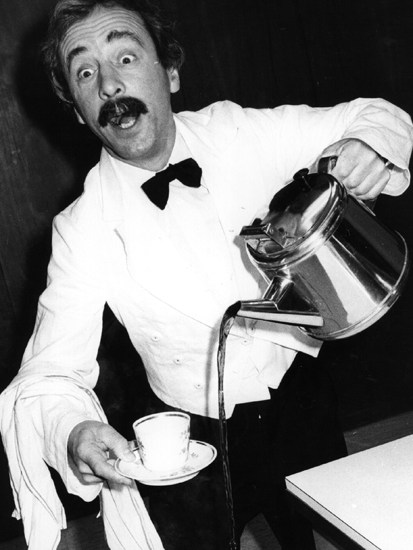

Farces with Brian Rix and Ray Cooney led, in 1975, to the offer from John Cleese for Sachs to play Manuel, the waiter from Barcelona, in Fawlty Towers. Nearly 40 years on, the programme is still being repeated in places like Argentina and Zambia; but are the jokes about dumb dagos and wops really very funny? What happens with comedy, over time, is that it becomes tragedy — and to see the show now, what’s affecting is Basil and Sybil’s terrible marriage and Manuel’s Sancho Panza-like devotion to Cleese’s mad Quixote. (Actually the only characters that still make me laugh are the dotty Major, the wittering old ladies, Bernard Cribbins saying ‘televisual feast’ and Joan Sanderson as the deaf harridan Mrs Richards. )

Sachs didn’t have much fun filming Fawlty Towers. He was concussed by a frying pan and set on fire in a kitchen scene. The BBC grudgingly paid him £700 in compensation, and the scars did heal after several years. But Sachs doesn’t like to make a fuss. As Cleese says, in real life Sachs is incredibly nondescript, like a civil servant or a provincial academic. This is his deliberate strategy, of course. The little boy from Berlin, keeping his head down.

The notorious phone calls from Jonathan Ross and Russell Brand, broadcast on a radio show in 2008, appear all the more shocking, therefore, now that we know about Sachs’s background and non-confrontational personality. It must have been like being picked on and bullied by Nazi thugs all over again. ‘He fucked your granddaughter,’ mocked Ross on Sachs’s answering machine. ‘He’s looking at a picture of her about nine on a swing.’

And on and on it went. Sachs provides a transcript. ‘They cursed,’ he says. ‘They jeered. It was a hugely distressing time for all of my family.’ This was a family that had escaped Auschwitz. Ross’s and Brand’s cruelty awoke nightmarish feelings of anti-Semitic persecution. The BBC received 18,000 complaints when the calls were transmitted, but Mark Thompson didn’t give a damn. ‘He considered his job was to investigate what had happened, not offer solace.’ Or display compassion and humanity.

Well, Brand has proved himself a petulant, rubbish actor in his subsequent films and Ross a prematurely fatigued codger with a repugnant Sid James cackle. The less said about them the better. And in the scheme of things, perhaps they were marginally less tactless than Sir Alec Guinness — who told Sachs that he’d be ideally suited for the role of Joseph Goebbels in Hitler: The Last Ten Days.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.00, Tel: 08430 600033. Roger Lewis is the author of The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, Charles Hawtrey and Growing Up with Comedians.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in