Last week, three exhibitions celebrating the art of Germany; this week, a show commemorating the first world war fought against that great nation. In this centenary year of the beginning of WW1, there will be numerous events marking the start of hostilities. (Will there be as many celebrating the anniversary of their cessation, I wonder?) Although there is some film footage of the war, and detailed photographic documentation of its horrors, the best record we have of the human reality of those five years of conflict resides in the art made about it. When the contagion of battle has passed from the blood, the conscious mind may turn to better things, and culture reassert its high priority. But in the midst of warfare art still has its unique purpose: to bear witness to the human condition and reassert a scale of human values in the face of destruction. Portraits play a key role in this affirmation.

The NPG’s free exhibition is quite small, but it encompasses a great deal. It begins with a masterpiece of Modernism: Epstein’s ‘Rock Drill’ (1913–16), a dramatic mechanised statement, though not as radical as it might be, since we see here the revised bronze version, not the original whole. Epstein cut down his powerfully phallic inhuman figure sitting atop a pneumatic drill — prophetic symbol of impending war — to an impotent torso, armoured head jerking to one side. Begun in 1913, its final manifestation three years later reflected Epstein’s changing attitude to the carnage. If he could do nothing about the conflict he could at least dismember the aggression of his own creation. This enigmatic symbol warns of the complexity of motive and historical meaning: do not take war at face value, it seems to say, but continue to question, however satisfying the first explanation may appear…

The exhibition then leads us straight into a cast list of top dogs, with a section devoted to portraits of crowned heads: Kings, Kaisers and Archdukes. These are not particularly interesting as works of art (the portrait of King George V, for example, is a copy of Luke Fildes’s 1912 painting), but artistic quality reappears in the next section, dealing with ‘Leaders and Followers’. Here a superb painting by Walter Sickert fairly leaps off the wall in the beauty and vivacity of its paint-handling. Entitled ‘The Integrity of Belgium’ (1914), it was based on newspaper photographs of Belgian soldiers resisting the German advance. Although not particularly well known, it is a fine piece of painting to enliven the eye and heart.

William Orpen’s portrait of Field Marshal Haig comes here, a masterpiece of sensitivity and directness. Orpen’s first portrait as an official war artist, it demonstrates his genius for capturing the nuances of character in the least flashy of ways. With Marshal Foch (also by Orpen) hanging next to him, we are presented with a more overt display of character and eccentricity, while the drawings and paintings of other ranks also in this room allow us to realise what a crucial role Orpen played in our understanding of this war, at all levels. In fact the exhibition is something of an Orpen fest. Even though there is a powerful painting on the end wall here, ‘The Dead Stretcher-Bearer’ by Gilbert Rogers, it is the image that makes the impact, not the way it is painted, which is crude and uninspired in comparison with Orpen’s touch. Either side of the Rogers hang Orpen drawings: ‘Royal Irish Fusiliers: Just come from the Chemical Works, Roeux: 21st May 1917’, and ‘A Man in a Trench: April 1917, two miles from the Hindenburg Line’. These images of resting and exhausted Tommies are a moving contrast to Orpen’s magnificently human but equally unidentified ‘Grenadier Guardsman’, in the full finery of oil. Next to it hangs C.R.W. Nevinson’s great painting of a machine-gun post, ‘La Mitrailleuse’, the height of mechanised soldiery, all angles and fractured fragments.

Continuing the Orpen show is his 1916 portrait of Sir Winston Churchill in despondent mood, just after his resignation over the Gallipoli disaster. Here, too, is a group of four pastels by the surgeon painter Henry Tonks (later famous as Professor at the Slade School) of horrifically disfiguring facial wounds. Various portraits of soldiers by such painters as Leon Underwood (better known later as a sculptor, and teacher of Henry Moore), Edward Newling and Colin Gill render factual and low-key accounts of these fighting men, among which the fresh vividness of Orpen’s style stands out, for instance in his portrait of Major J.B. McCudden, the most highly decorated British pilot of the war. There’s also a memorable Daumier-like pencil and watercolour drawing by Orpen of ‘The Receiving Room: the 42nd Stationary Hospital’, featuring three wounded Tommies awaiting treatment.

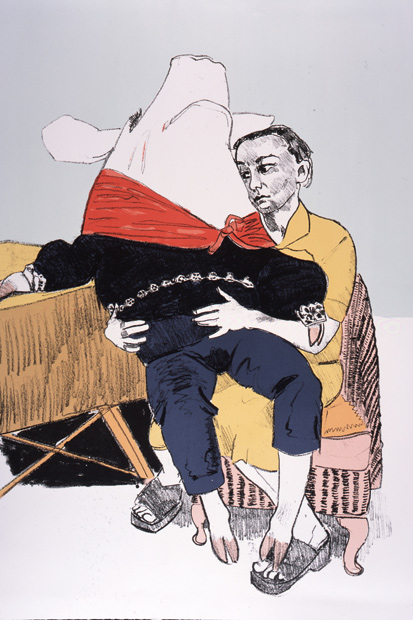

Next to it Eric Kennington’s ‘Gassed and Wounded’ (1918), an oil based on drawings made at a Casualty Clearing Station, records the crowded conditions in these behind-the-front-lines medical facilities. The shallow space and deep shadow of Kennington’s composition adds an element of faceless horror to the scene, compounded by the trailing arabesques of what is presumably mustard gas across the front of the picture. In this section there are also self-portraits: the sensitive and doomed Isaac Rosenberg, killed at the age of 28 on the Western Front; dare-devil but factual Orpen, painting himself drawing in a tin helmet; the marvellous hallucinogenic cynicism of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s portrait of himself in uniform, his right hand severed at the wrist, indicating his symbolic unmanning as an artist. The show ends with Glyn Philpot’s slightly effete portrait of Siegfried Sassoon, opposite Max Beckmann’s savage post-war lithograph ‘Hell: The Way Home’ (1919).

By way of complete contrast, and indeed of spiritual respite, I would like to mention an exhibition of the latest paintings on paper by Luke Elwes (born 1961). These are being shown in the Adam Gallery’s new London premises, whereupon they will transfer to the gallery’s Bath headquarters. Over recent years, Elwes has been developing a language of near-abstract touches of floating colour in shifting patterns, shattered and elliptical, like confetti on a cobbled pavement that is also a river. (If you’re looking for comparisons, the nearest I can come is to the American painter associated with the Abstract Expressionists, Mark Tobey.)

This flexible and evocative language has reached a new peak in a series of paintings made in Vermont during a month’s residency last year, exploring the wild landscape of the Green Mountains and the Gihon River that flows through it. The style and technique (a mixed-media secret closely guarded from his many would-be followers) is admirably suited to depicting the reflective and troubled surface of moving water, and Elwes puts all his skills to good effect in this magnificent new series. A source of contemplation in turbulent times: recommended.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in