Listen

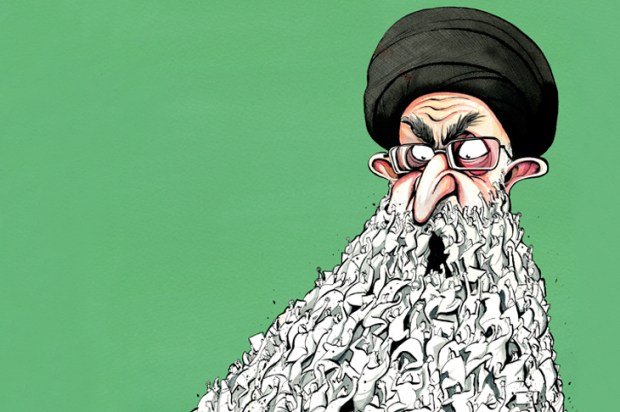

What was your reaction recently when it emerged that thousands of unborn foetuses had been burnt by NHS trusts? And that some had been put into ‘waste-to-energy’ incinerators and so used to heat hospitals?

Revulsion, I would imagine. But why? I would hazard that it is either because you are religious or because your customs and beliefs are still downstream from faith, even if you reject it. Because if you grant that an unborn foetus is not a life and that once aborted it could have no further use, there is at least an argument that these bodies might as well be put to use. Why not use unwanted babies to keep a hospital nice and warm?

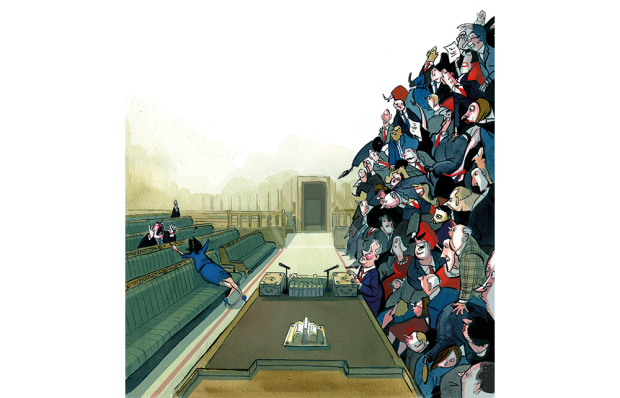

It isn’t such a ridiculous argument. And it is time that atheists and non-believers began to take such stories — and their follow-on questions — as seriously as believers do. As Jonathan Sacks wrote in this magazine last year, when he was Chief Rabbi, atheists tend to imply that there isn’t much work to do after discarding God. On the contrary, after discarding God, all the work of establishing morals is still before you — just as after demonstrating mankind’s need for ethics, the work of proving a particular religion is true remains before you.

But this greatest challenge in the atheist argument remains the one we hear least about. As Sacks pointed out, it is increasingly clear that, contra most atheists, ethics are self-evidently not self-evident. They vary wildly from era to era, and many Judeo-Christian ethics may well, as T.S. Eliot put it, ‘hardly survive the Faith to which they owe their significance’.

There is a perfectly good utilitarian argument for putting dead babies into a hospital furnace. And if the foetuses are genuinely unwanted, then burning them instead of fossil fuels means we plunder fewer natural resources of our ailing planet. I cannot see that the action greatly trespasses John Stuart Mill’s ‘harm principle’.

If all this sounds far-fetched, we should look back only a century, when entire schools of very intelligent non-believers could discern no moral objection to eugenics. Religion holds back the religious (even if not always stopping them). But today, despite the moral qualms which the extremes of eugenics posthumously bestowed upon us, there is no reason why atheists should not again go down such paths.

We continuously see the uniqueness of life being whittled away at all ends. With each year that goes by in increasingly post-Christian societies abortion becomes less and less of an issue. Too few atheists make arguments as passionate as those of believers over the aborting of unborn infants if they are of the ‘wrong’ sex, have some birth defect or a harelip. Even in America, which remains a significantly more religious country than ours, initially there was limited outrage at the trial last year of Kermit Gosnell, a Philadelphia physician discovered to have been carrying out ‘post-birth abortions’ — or child murder, as we might once have called it.

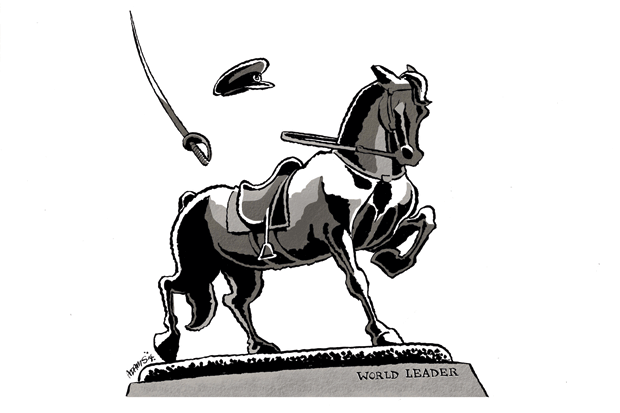

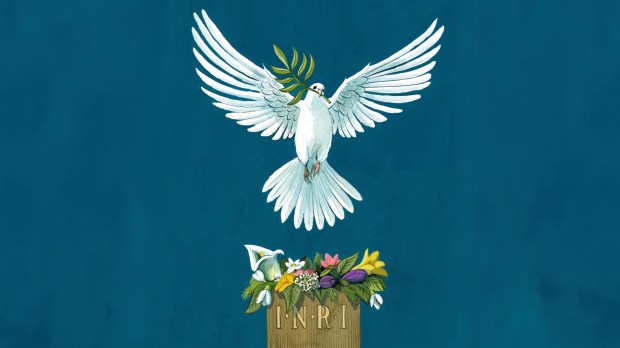

At the other extreme of life, we watch euthanasia become ‘assisted dying’ and the argument tilting in its favour. More and more it is about granting people a ‘humane’ end, rather than focusing on what such a move does to the significance of life as a whole. The treatment of bodies after death is another example. We have never cared less about what happens to our bodies after death. And this unconcern applies retrospectively. When digging up ancient burial yards, the fact that many of the bones being flung around come from people who went to their graves in the sure and certain hope of the Resurrection isn’t enough to dampen our appetite for eviction if a property development is at stake. Does an atheist lack of concern for the physical body show a great devil-may-care attitude — or demean the significance of the vessels we spend our lives in?

And so it goes, on and on. Most obvious at the extremities of life, the decline of the Christian concept of the self can be seen everywhere, not least the concept of human love as a quasi-divine thing.

The more atheists think on these things, the more we may have to accept that the concept of the sanctity of human life is a Judeo-Christian notion which might very easily not survive Judeo-Christian civilisation. Those who do not believe in God and who stare over that cliff — which as Theo Hobson points out, very few atheists actually do — may realise that only three options remain open to us.

The first option is to fall into the furnace. Another is to work furiously to nail down an atheist version of the sanctity of the individual. If that does not work, then there is only one other place to go. Which is back to faith, whether we like it or not.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in