You may not have heard of Goldie. He’s an actor and singer whose name refers to the bullion with which a cosmetic mason has decorated his incisors. A recent James Bond also featured a glimpse of the Fort Knox gnashers, and they’re currently on display at Stratford East in Roy Williams’s new drama Kingston 14. Goldie, and his high-value gob, plays a Jamaican gangster named Joker suspected of murdering a British businessman.

Curtain up and a small riot is in progress inside the cop shop as Joker gets hauled in for questioning by a gang of jumpy detectives. A great deal of comic kerfuffle ensues. A British detective arrives from London to help with the investigation. His parents were born in Jamaica but he exudes charm and urbanity as if he were a duke’s son educated at Harrow and Oxford (like so many black British policemen). His bungling naivety provides more entertainment as the Jamaican coppers ridicule his accent and his punctilious approach to detective work.

But the tensions between Brits and West Indians are a sideshow here. Williams’s main concern is the relationship between a kidnap victim and his young abductor, whom he attempts to rescue from a criminal career. These scenes are moving, unpredictable and dramatically valuable but they’re staged in a little cubby-hole on wheels that gets trundled on and off stage, as required. This mars their impact enormously.

Like all Williams’s work, this play is horribly violent, unflinchingly honest and extremely funny. But the take-home message is wretched: everyone is doomed to lawlessness, squalor and despair. In the closing scenes two foul-mouthed deadbeats bewail their island’s position as the helpless plaything of external interests beyond their control. Once it was the vassal of Britain’s racist colonialism, now it’s the functionary of America’s philistine commercialism. To brighten the mood, Williams drops in a sugary curtain-scene in which a redeemed character takes a grieving matriarch down to the beach and massages her tootsies in the surf while feeding her slices of melon. But we need a much stronger pick-me-up than that.

As for Goldie, his role barely ranks as a cameo. Joker is a thuggish mascot, a weapon with a heartbeat, an emblem of brutalised aggression who undergoes no change or growth in the course of the play. Goldie has little to do but stride around looking exceptionally pleased with himself. And this, I’m sorry to report, is a task he performs with world-class aplomb.

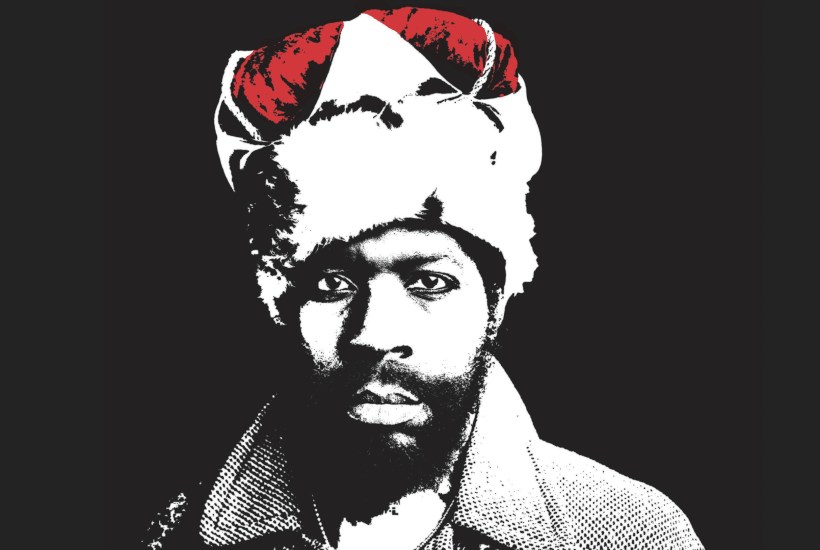

Banksy: The Room in the Elephant examines the fascinating question of biographical copyright. Who owns the rights to your story? You? Or some chancer who pops up and turns it into a lucrative work of art? This is what happened to Tachowa Covington, a homeless actor who took refuge in a cylindrical water tank beside a Hollywood freeway. One day Banksy stumbled on the aluminium bedsit and asked the occupant for permission to adorn its flanks with a witty caption. Sure, said Covington, knowing nothing of Banksy’s work and reputation. Several tins of paint later, the words ‘this looks a bit like an elephant’ had appeared across Covington’s rusting penthouse. Banksy, I would suggest, has done better work. The tank resembles no animal in creation except, perhaps, a decapitated albino dachshund.

As soon as Covington’s squat became a Banksy masterpiece, the moneymen showed up and bulldozed it to a fancier location. Evicted, Covington took up residence in a toilet, then in a cave, and ended up living under a hillside tarpaulin. He’s an intriguing and resourceful character who dresses with majestic flamboyance and surrounds himself with gorgeous bric-a-brac collected during his wanderings. He’s also handsome, melancholy and black, and he once appeared in a James Caan mega-hit, Rollerball. These details, taken together, offer a living symbol of Hollywood’s cruel habit of randomly destroying creative promise.

Covington’s story forms the basis of a play by Tom Wainwright that the Arcola presents alongside a documentary, Something from Nothing, by Hal Samples. It’s the film that reaches closest to the heart of Covington’s tragedy. We watch him at the Edinburgh Festival being applauded on stage after a performance of Wainwright’s play about him. The crowd relishes his quiet, forceful demeanour and his self-mocking visual style: green kilt, purple trilby. So why is he not doing his own show at Edinburgh? The film then cuts to him alone in a festival flop-house, weeping, and it becomes clear that this question means more to him than to anyone. Every creative life rests on two pillars. You need talent and you need the talent to manage your talent. If you’re deficient in the second category you’ll fail. Covington is doubly unlucky in that he’s now haunted by a film-maker and a playwright who keep reminding him that he has no natural ability to manage his natural ability. Harsh but true.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in