How important is William Kent (1685–1748)? He’s not exactly a household name and yet this English painter and architect, apprenticed to a Hull coach-painter before he was sent to Italy (as a kind of cultural finishing school) by a group of patrons who recognised his abilities, became the chief architectural impresario and interior decorator to the early Georgian nobility. His Italian studies made him a devoted Palladian, and in partnership with his principal collaborator Lord Burlington he set about transplanting the architectural principles and beliefs of Andrea Palladio to the English countryside. He was probably a better ideas man than artist (the Damien Hirst of his day, perhaps?), but he had access to the finest craftsmen, who could execute his plans to great effect.

Horace Walpole called Kent ‘the father of modern gardening…He leaped the fence and saw that all nature was a garden.’ His ideas were expanded and developed by the far more famous ‘Capability’ Brown (the English do love a garden), but it was undoubtedly Kent who pioneered this attitude, as the grounds of Stowe and Rousham bear eloquent testimony. He was a designer rather than a horticulturalist, and this conceptual approach marked all his endeavours. He designed furniture and metalwork, dabbled in book illustration, theatrical design and costume, besides his principal interests in painting, sculpture and architecture. His drawings are sometimes piquant but are rarely beautiful or aesthetically first-rate — they are working drawings intended to convey his ideas, and in that they succeed.

As a conceptual artist, it is surely appropriate that a good proportion of Kent’s designs never got further than the ideas stage — and were never made real. He submitted proposals for a new Parliament building (1733–40) and for interiors in the existing House of Lords (1735–6), and designed a splendid-looking summer Royal Palace in the Anglo-Palladian style for Richmond. It was never built, but there is a great oak and pear-wood model in the exhibition which gives a good account of what it might have looked like.

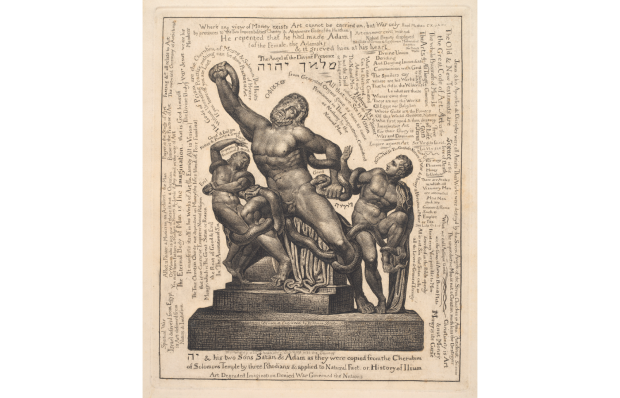

Such exhibits bring the exhibition more to life than the rather smug portrait of Kent by William Aikman, in the first room, though the case of books below it gives a clear indication of the scholarly nature of the whole project. (The books include Shaftesbury’s A Letter concerning the Art, or Science, of Design, The Spectator of 1712 by Joseph Addison, The Architecture of Palladio and Vitruvius Britannicus, or the British Architect by Colen Campbell.) There are some studies by Kent after such Old Masters as Annibale Carracci, Domenichino and Carlo Maratti, and then the infinitely better portrait of Lord Burlington by Jonathan Richardson. Here are a couple of drawings by Kent, rather in the style of Inigo Jones, intended as studies for sculpted portraits of Palladio and Jones. Once again the style of labelling fashionable among our museums leaves a lot to be desired. It’s as if the exhibition’s designers have a horror of labelling the actual exhibit, preferring to group the labels in a distant corner in order to preserve the surfaces and spaces of their installations in pristine condition. The fact that this habit does not best serve the public seems of very low priority.

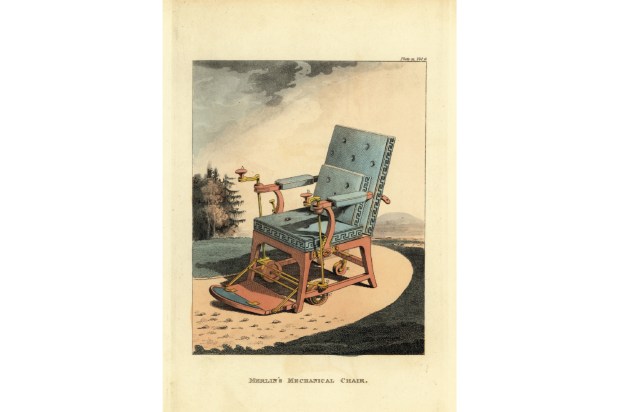

Kent’s furniture is represented by such things as an armchair and stool from the Red Salon at Houghton Hall, decked out in crimson fabric and ornate decorative carving with Venus masks on the knees of both. These form part of a long parade of objects which don’t make much sense or confer much pleasure or instruction. Meanwhile, the air is filled with sprightly (or should that be spritely?) music. There are inevitably things from Lord Burlington’s Chiswick House, and an amusing little drawing of William Kent at his desk, a portly man making drawings. This is attributed to Dorothy Boyle, Burlington’s wife, and hanging next to it is a rather poor drawing by Kent of her in her Garden Room, with outsize left hand gesturing at another drawing, in a room full of furniture designed for her by him. There are lots of architectural drawings of limited general interest (endless elevations and details), and the designs and model for a Royal Barge, with two massive painted pine oars. William Shakespeare leaning on a pile of books is another successful and popular design.

The exhibition is accompanied not by a catalogue but by a vast hardback publication over two inches thick, running to 690 pages and containing a superfluity of text by more than a dozen different authors (priced at £45). This may indeed be the ideal publication for a William Kent enthusiast, though even that minority would find it difficult to consult without a table to prop it on, or preferably a lectern. This is not a tome to read upon one’s knee, nor in bed. It would seem to be a classic example of that outworn fallacy that bigger is better, and biggest is best, a great favourite with Americans. No surprises, then, to discover that the book was co-produced by the Bard Graduate Center of New York City, where the exhibition was first shown last year. Who will read such a monster? You cannot bolster a slim reputation with an overblown publication. Even the scholarly argument for an exhaustive record of an artist’s output is vitiated by this example of academic elephantiasis.

The exhibition is neither emotionally captivating nor visually thrilling. With some 200 exhibits, it is rather crowded, but for those who enjoy visiting country houses and traipsing past their rather frozen and lifeless displays, this might well be the perfect show. Whether it does justice to William Kent is another matter. Architectural exhibitions are always difficult to animate, but at least a couple of slide shows of ornamental interiors, and external statues, follies and grots liven things up a bit. Was Kent simply a successful jack-of-all-trades? No, he had a real genius for design, for thinking beyond the expected, which brought him important commissions that lastingly affected the art and taste of his own time, and of subsequent generations. But conveying that successfully is not an easy task. Some of the drawings here suggest the originality of his thought, such as ‘Proposal for the hillside at Chatsworth’, or the trio done for Euston Hall in Suffolk, particularly ‘Design for the park with distant triumphal arch’. And I liked the amusing brown wash drawing of Alexander Pope in his grotto at Twickenham. But to bring Kent’s spirit alive, it is perhaps best to visit the great gardens he created — not an exhibition.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in