Jankel Adler (1895–1949), a Polish Jew who arrived in Glasgow in 1941, was invalided out of the Polish army, and moved to London two years later. A distinguished artist in his own right, he turns out to have been a hidden presence on the English art scene, a secret influence on indigenous artists. He is usually cited as a crucial inspiration for Robert Colquhoun, but as his work grows more familiar, it becomes clear that a whole host of other artists must have been aware of him, from S.W. Hayter to Cecil Collins. Interestingly, the sculptors who were coming to maturity in the 1950s (just after Adler’s death) also seem to owe him a debt: the so-called ‘Geometry of Fear’ generation of Armitage, Butler and Chadwick, to which I’d add Robert Adams and George Fullard. Picasso is often named as the chief influence on Adler himself, but actually Klee emerges as the key inspiration, the two artists becoming friends in the 1930s at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts.

Adler’s distinctive line, at once loopy and angular, questing and rhythmically enfolding, explores an essentially tragic and anarchic view of the human condition. Many of the figures in this remarkable exhibition of 100 paintings and drawings at Goldmark Gallery (14 Orange Street, Uppingham, Rutland, 17 May – 25 July) are solitary if not lonely (Adler lost all his family in the Holocaust). Some are brushy yet ghostly, as if emerging from a coloured fog, lit by oddness and humour, but with visual wit to combat the bleakness. Other images move towards the abstract: decorative, even jewelled, still-lifes, and stacked forms. His friend Josef Herman quoted him writing in a letter: ‘In the 20th century a new aristocracy came into being, an “aristocracy of the spirit”. It is here that the modern artist belongs.’ There is hope then in his work: the caged bird at last flies free.

Adler was both a painter and printmaker, and Norman Stevens (1937–88) also operated in both media, beginning as a painter, but making his most innovative work in prints. He was one of a talented group of students at Bradford College of Art, of whom the best known is David Hockney. Stevens died tragically early (like Adler) and his work is not now as well remembered as it should be. The current exhibition at the Royal Academy, in the Tennant Gallery and Council Room (until 25 May, but check opening hours), does something to bring his achievement back into focus. In the Gallery Guide, William Packer remembers him with deep affection as ‘cantankerous, generous, funny and, above all, loyal’, and as ‘one of the foremost printmakers of his generation’.

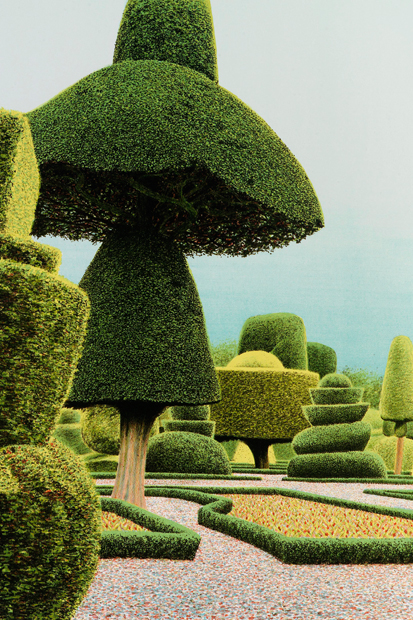

An immensely gifted draughtsman, Stevens was largely self-taught as a printmaker, concentrating to begin with on black and white etching, to which he added aquatint and mezzotint, before exploring colour screenprints in the 1980s. His compositions never contain figures, though there is nearly always an implied human presence, and his subjects were chosen for their formal, rather than narrative, values. His principal theme was the fall of light on foliage and architecture — clapboard houses with slatted shutters, the louvered blinds of hotel windows, palms, lilies, topiary. The Tennant Room shows his early development through etchings of American and English subjects (‘Painswick, Moonlight’, 1979, is especially memorable), with four flat cabinets of small works in the middle of the room (note the very beautiful, hand-coloured Stonehenge series), and larger prints on the walls. In the Council Room are the later screenprints, including ‘Black Walnut Tree’ and the wonderfully vivid ‘Fallen Tree, Kensington Gardens’, both commemorating the great gale of 1987. The quality of the work speaks for itself: well worth a visit.

Mick Rooney (born 1944) is a Royal Academician much cherished by a growing band of supporters who relish the inventions of his fecund imagination. Rooney himself claims that he is a painter ‘clearing out the attic — that’s what I do’. In which case, his attic is particularly well stocked with choice lumber: such stuff as dreams are made on. His dreams are lucid, even serene, for all their incongruity of image and vaporous layering. Love and loss, adventure, the world of the symbolic at the service of ‘our daily struggle to make sense of our fate’ — these things cohabit and cohere in Rooney’s beguiling tableaux. There is nothing unreal about his visions, which are effortlessly convincing whether they depict mermaids, a wrestling match, a circus troupe or a low-flying angel. A 70th birthday exhibition at the Fosse Gallery (The Square, Stow-on-the-Wold, 11 – 31 May) reveals the magic lurking in the shires — and at the end of Rooney’s brush.

When Alan Davie died full of years at the beginning of April, the news coverage was disappointingly muted. Here was an artist who had been at the forefront of the European response to American Abstract Expressionism (he’d seen the work of Pollock and de Kooning as early as 1948), and who had carried on developing and extending his art through a long and productive lifetime. But instead of proper assessment of his entire career, there was the usual knee-jerk response that Davie’s early work was his best, and that he’d subsequently declined into exotic pictographic image-making that was wilfully literary and obscurely shamanic. In 1948 Davie wrote: ‘I believe that it is only through long and laborious specialised work of an experimental nature that I shall be able to evolve a satisfactory symbolism by which to bring my new vision to life.’ That determination to explore the wellsprings of his creativity never left him, and can be seen in an exhibition of marvellously fresh recent paintings at his long-time dealer Gimpel Fils (30 Davies Street, W1, until 23 May). Davie was prolific, and other dealers have taken an interest in his work. Alan Wheatley is showing early paintings at his premises in Mason’s Yard, SW1 (until 23 May), while Portland Gallery (8 Bennet Street, SW1) is mounting a substantial selling and loan exhibition (until 5 June). Let’s hope that Davie will at last begin to attract the recognition he deserves.

Finally, at Messum’s (8 Cork Street, W1, 14 May – 15 June) is an exhibition by an artist I have written a book about and so may be forgiven for favouring. Brian Horton (born 1933) is a landscape painter of elegiac poignancy. Not for nothing is he an admirer of A.E. Housman, but he mingles the sadness of lost time with a thorough-going admiration for the developments of British Modernism — for the paintings of John and Paul Nash, Ivon Hitchens, Ben Nicholson, Graham Sutherland and Edward Burra. These inspirations and influences feed into his work and lend a touch of abstraction to his pastoral vision. Working in gouache or mixed media (with some finely finished pencil drawings to point up the subtlety of his colour), Horton evokes the spirit of the English and Welsh countryside. Formally they are tougher than they may at first seem, but in the final analysis these pleasing paintings are grandly modest celebrations of the natural world that surrounds and nurtures us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in