In many respects the average art-lover remains a Victorian, and the Florentine Renaissance is one area in which that is decidedly so. Most of us, like Ruskin, love the works of 15th-century artists of that city — Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Ghiberti — and are much less enthusiastic about those of the 16th. But a superb exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism, might change some minds.

It contains pictures that are intense in emotion, eccentric, mysterious, sometimes bizarre and — to a 21st-century eye — appealingly neurotic. Rosso Fiorentino and Pontormo were almost exact contemporaries, born within a few months of each other in 1494. Their training was similar, they shared many influences, and yet as the subtitle of the show implies, they were very different artistic personalities.

The exhibition begins in the second decade of the 16th century. At that point, the great masterpieces of the High Renaissance were so new the paint was still drying. It seems that Rosso and Pontormo probably visited Rome in 1511 and saw Michelangelo’s still unfinished Sistine ceiling and the frescoes that Raphael was painting in the papal apartments. Even before that, the two young artists — 17 in that year — had seen the works in Florence by Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo. These were an inspiration, but also a dilemma. How to absorb these overwhelming influences and retain one’s individuality?

As the exhibition unfolds, one can trace the two men taking very different paths. Jacopo Carrucci, known as Pontormo after the village of his birth, was able to blend elements of the three great High Renaissance styles — Raphael’s compositional architecture, Leonardo’s soft shadow and tender naturalism, the athletic poses and acid colours of Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling — into an enigmatic personal language.

That is clear from his early masterpiece, the Pucci Altarpiece (1518): a sort of sacred firework, in which saints, Madonna, and naked holy toddlers whirl round in a catherine-wheel of naked limbs and singing colours. Looking out from it all, giving the picture its emotional tone, are Pontormo’s round-eyed people with their characteristic gaze, melancholy and yearning.

Rosso was more capriciously changeable. He made a brilliant debut in the earliest work in the exhibition: a single figure fresco in the ‘Journey of the Magi’ by Andrea del Sarto (his master and also Pontormo’s). This youth, in an eye-catching violet cloak, turns his head, fixes the viewer with his eye — and effectively upstages the rest of the picture. It is like a declaration: a new art star has arrived.

Rosso was an artist, and a man, who wanted to attract attention to himself. According to Vasari, he kept an intelligent but larcenous ape as a pet in his studio. He was of humble origin (his real name was Giovanni Battista di Jacopo; Rosso just means Redhead), but he ended up living like a prince in France as court painter to Francis I. Earlier he led a wandering life.

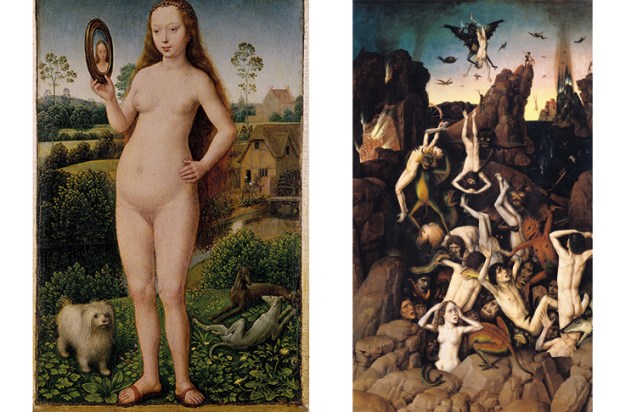

His art could be downright peculiar but also brilliant. Among the Apostles in his ‘Assumption of the Virgin’ are faces so caricatured as to be ludicrous. Rosso’s designs for engravings of classical mythology — done in Rome in the 1520s — were wildly inventive, verging on obscene, and full of absurd details such as the lovesick horse in ‘Saturn and Philyra’. In contrast, the Pietà (1538–40) is so full of vehement religious feeling as to seem medieval.

This is the key to understanding both Rosso and Pontormo. Their art can seem frivolous, with its sumptuously pretty colours and extravagant flourishes. But they lived at a time of passionate piety. By the time Pontormo died in 1557, the Reformation had taken place and the Counter-Reformation was well under way. There was a conflict between the extreme artistry of their art and the increasing puritanism of the age, which may explain why Pontormo’s late masterpiece — a huge fresco of the ‘Last Judgment’ full of undulating nudes — was subsequently destroyed. It must have looked unseemly.

But in his greatest works Pontormo held intense feeling and painterly loveliness in balance, never more so than in the weird and marvellous ‘Visitation’, which ends the exhibition. The billowing draperies in his trademark orange, lime-green, blues and pinks are fabulously beautiful; the emotional tone is almost surreal. Behind the embracing figures of the Virgin and St Elizabeth, two other women stare out — unexplained by art historians — like witnesses and alter egos of the couple in the foreground.

One leaves feeling Rosso was a fascinating oddball, but Pontormo was a truly great painter. While this show is on, almost all of Pontormo’s greatest works can be seen in and around Florence. It’s hard to think of a better way to spend a few days than looking at them.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in