What the title promises is not found inside. It is a tease. John Sutherland says he has ‘been paid one way or another, to read books all my life’, yet he does not regard himself as well read in the genre of novels. With two million languishing in the British Library vaults, nobody could be, he insists.

And although the publishers have given it the subtitle ‘A guide to 500 great novels and a handful of literary curiosities’, the author declares in his admirably succinct preface: ‘This book is not a guide.’ He’s right. It is an engaging game, or a compendium of games (as the Gamages Christmas catalogue used to describe a chess board with snakes and ladders on the back). I started off by seeing what the Prof thought of some of the books I like.

Of The Diary of a Nobody (1892), he makes the enlightening point that the ‘Nobody’ of the title is very hard to translate, being rooted in English class. It is true that the French inconnu doesn’t answer, but aren’t there hints of something similar in the Spanish antonym hidalgo ‘son of something’? Only an hidalgo could call himself ‘Don’. In Spain the book is known as Un Diario de Don Nadie. For me, the world is divided into those who identify with the Nobody, Charles Pooter, and those who despise him and side with his rebellious son Lupin. Though most unPooterish, Sutherland, perhaps with his Lupin years behind him, is glad things turn out well for Pooter.

Another great divide is to be found in A Child of the Jago (1896), the slum novel by Arthur Morrison about the no-go area for toffs, the Nichol, surprisingly near Bishopsgate. Does the narrator despise the people he describes, as moral freaks, or does he glorify their brutal lives? Sutherland quotes the still shocking description of a woman using a broken bottle in a fight. He then relates it to the gang world of the LA rapper Tupac Shakur, which may be fair but does not make the novel sound enticing.

Sutherland invites disagreement. He is right to warn against allegorising The Hobbit (1937), but who would call the story ‘intensely enjoyable’? Its merit surely lies in its myth-making. Then, although he acknowledges that humour, ‘like milk, goes off very quickly’, he calls the 500 words on Jim Dixon’s hangover in Lucky Jim (1954) ‘the funniest thing ever written in British fiction’. Is it? The Riddle of the Sands (1903) may be a ‘secret agent docu-novel’ but its remarkable achievement is to turn detailed descriptions of sailing into a memorable novel.

As these examples suggest, Sutherland is not worried about the highbrow/lowbrow division. Dead Cert (1962) by Dick Francis nestles happily next to Dead Souls (1842) by Nikolai Gogol. ‘Literature is a library,’ he declares, ‘not a curriculum or a canon.’ The focus is on reading for pleasure, which is not the same as airport reading. He reads Crime and Punishment (1866) for pleasure, implicitly the right way to read.

So, to praise Tristram Shandy (1759–67) he says that it is ‘replete with jokes which could have found a happy home in the movie Airplane!’ I’m not sure that helps. He mentions the comic incident in which the boy Tristram ‘just this once’ (since the chamber pot is missing) pees out of the nursery window and is caught by the falling sash window. But he is wrong to say that this is because Mr Shandy has ‘for years omitted to mend’ the window. It was the door-hinge that he neglected (and its creak wakes him as he dozes, awaiting Tristram’s birth). The window falls so painfully because Corporal Trim has taken the lead sash-weights to make cannon for Uncle Toby’s model battleground. To mention this sounds pedantic, but Sutherland likes the game of pedantry as much as anyone.

He begins his entry on Wuthering Heights (1847) with an admirable piece of pedantry, pointing out that the Oxford English Dictionary is unable to come up with a convincing example of anyone using the word ‘wuthering’ before Emily Brontë. He’s right. The OED entry for ‘wuthering’ comes under the head-word ‘whither (verb)’. So perhaps the publisher should have changed the title to Whithering Heights. Sutherland poses a perplexing puzzle about Heathcliff, the anti-hero of the book: ‘Why are we so drawn, sympathetically, to this brute of a man (if that is what he is), who beats up women and, cardinal sin, kills puppy-dogs out of sheer malice and abuses children?And, quite likely, kills people.’ Sutherland says he has never found a satisfactory answer. He even published a book in 1996 called Is Heathcliff a Murderer? The lack of an answer is, he suggests, a reason that he and others read the novel so often.

He also admires the ‘pedantically exact inventory’ of what Robinson Crusoe salvages from the wreck. In another playful book (Can Jane Eyre Be Happy?, 1997) he had asked why there was only a single print of a foot on the shore of Crusoe’s island, as evidence of Friday’s presence. One was certainly enough. ‘I stood like one thunder-struck,’ the narrator recalled.

My own thunderstruck moment in the present book came in the entry on Don Quixote (published in two volumes in 1605, 1615). It is, he writes, ‘a work that everyone knows but very few (I indict myself) will actually have read from cover to cover’. What! He hasn’t read it? This was like watching William Webb Ellis, who, as his memorial says, ‘with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time first took the ball in his arms and ran with it’, thus inventing rugby. (I realise the tale is dubious.) Sutherland seemed to be changing the rules of the game half way through.

Yet I suspect that he has read cover to cover perhaps 498 of these 500 books (there’s another one in doubt that I won’t go into), and thousands more. It is precisely the occasional drift from accuracy that demonstrates he has read them and incorporated them into his memory. Just as to translate is to traduce, so to remember is to remake. Damn the canon, says Sutherland, enjoy a wider vision. The reward is not to find out how to be well read, but how to read well.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

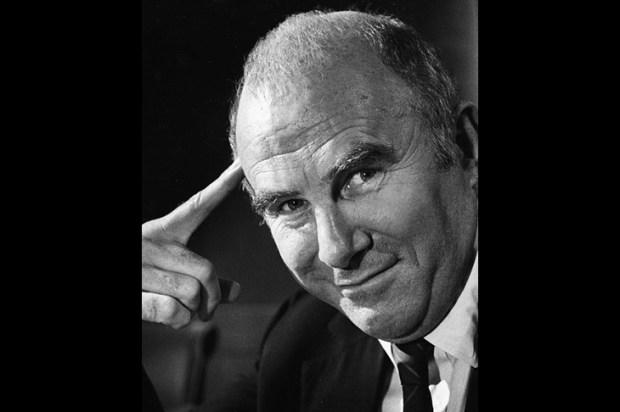

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16. Tel: 08430 600033. Christopher Howse, writes leaders, features and reviews for the Daily Telegraph, and ‘Portrait of the Week’ for The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in