Personally, I have always been sensitive about a credibility gap, a difference in prestige, between literary and visual cultures. More than 30 years ago, Frederic Raphael wrote a teasing piece in the TLS mentioning an Italian designer with a funny name, as if to disparage design as a whole. I boldly wrote in defence and, surprisingly, my letter was published. That designer was Ettore Sottsass, Jnr (1917–2007).

The ‘Jnr’ was not mere affectation, although there was a bit of that. His identically named father had also been a distinguished architect. (The curious name is Romansch, meaning ‘under the stone’). Sottsass, born in what used to be Austria before it was Trentino-Alto-Adige, became a prominent figure in Italy’s postwar ricostruzione, its industrial revolution which gave us the epochal Vespa and the Fiat Cinque-cento. First as an architect of dignified social housing, then as a designer for Olivetti, the manufacturer of typewriters and electronics which, in that attractive Italian way, was both an employer with lofty social principles and an inspired patron of the arts.

It was Sottsass who determined the appearance of the first Italian mainframe computer, Olivetti’s Elea 9003 of 1959. Soon after, he was saved from a mortal health crisis when Olivetti paid for treatment at Stanford University Medical Center in San Francisco. Recuperating, he got to know the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the City Lights Bookshop crowd, including Kerouac’s fellow-traveller, Neal Cassady. Thus it is pleasing to note that the designer of Italy’s first computer was connected to the Beats and the Bay Area drug scene. That ‘Jnr’ appendage revealed a lifelong romance with the hipper versions of Americana.

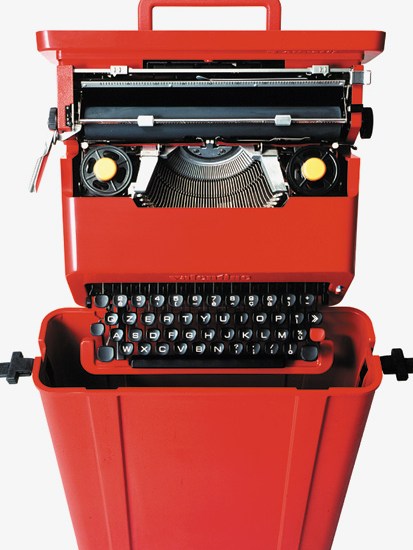

By the time we met in Milan in the late 1970s, Sottsass was surrounded by an adoring tribe of international acolyte-trainees in ‘Sottsass Associati’. He drove an old Opel, absolutely mummified in ossified pigeon droppings to confuse the Red Brigades. A contemporary project was an Alfa-Romeo with Astroturf instead of carpet and a blue sky head lining (which Alfa disowned). He had his table at the Torre di Pisa and lived in a small flat in the Piazza Diocleziano with comic-strip dinosaur pictures sellotaped to the wall. There was a record player with Rod Stewart vinyl: ‘e molto ironico’ was a favourite expression. He said ‘I am always quoting from suburbia’: the banal fascinated him.Few people have been more influential in modern material culture. My own first typewriter was a Sottsass-designed Olivetti Dora (now in the Design Museum), a shockingly beautiful device from which I was, aged 12, inseparable. His bright red plastic Valentine portable typewriter was intended for use in boutiques and discos, the iPad of its day. It was a sensation in 1969. Sottsass always invested complex industrial products with playfulness: I used to lecture students on machine aesthetics using slides with colourful deconstructed details of an Olivetti text-editing-system (as early personal computers were known).The health scare inclined him to a lugubrious mysticism, later sustained by many trips to India. By the late 1960s, Sottsass had become the original design guru, a spiritual leader of the Anti-Design movement which rebelled against Italy’s (really rather admirable) commercial exploitation of design and designers.

Now Sottsass began a third career. His every disruptive tendency was, with many willing helpers, channeled into a design group called Memphis whose name was a reference both to Egyptology and to Elvis. (I lent him the Chuck Berry ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ single for the Milan launch party in 1981). ‘Why should homes be static temples?’ Sottsass asked, as he showed the po-faced establishment furniture that was so crazily irrational it made you laugh out loud. At least for a while: Memphis was easy to copy and Sottsass came to regret his influence on the meretricious, trans-sexual, lame-joke, feeble-minded wave of Post-Modern imitators.

His achievement was far greater and lasting, as Philippe Thomé, a Swiss art historian and long-time collaborator, shows in this gorgeous book. With very well-informed essays by Francesca Picchi, Deyan Sudjic, Emily King and Francesco Zanot, it has a quirky sculptural presence all its own and comes in a very Sottsass pistachio ice-cream cover (with blink-making zebra stripe endpapers). Here is a suitable memorial to an exceptional life: eclectic, serious and detailed as well as delightful, surprising and utterly inspiring. The production is faultless, and superlative pictures illustrate, both precisely and anecdotally, the vast range of Sottsass’s work: buildings, furniture, paintings, jewellery, ceramics, glass, graphics, office equipment.

Alas, there is no way even so thorough a book can capture the lovely poetic cadences of Sottsass’s English nor the astonishing way he pronounced ‘Stonehenge’; but as a demonstration of what ‘designer’ really means, it is thrilling. I am going to ask the publishers to send Frederic Raphael a copy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Stephen Bayley’s latest book is Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything. Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £90. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in