I watched the new DVD of Gregory’s Girl on the train from London up to Edinburgh. I hadn’t seen Bill Forsyth’s school-yard comedy in more than 30 years. Incredibly, it hasn’t dated in the slightest. When I saw it in the cinema, in 1981, as an acne-ridden adolescent, this tender romance was a revelation — for me, and millions like me. Funny yet heartfelt, it was that rare and precious thing — a rite of passage movie that was neither patronising nor pretentious. Half a lifetime later, Gregory’s Girl still rings true.

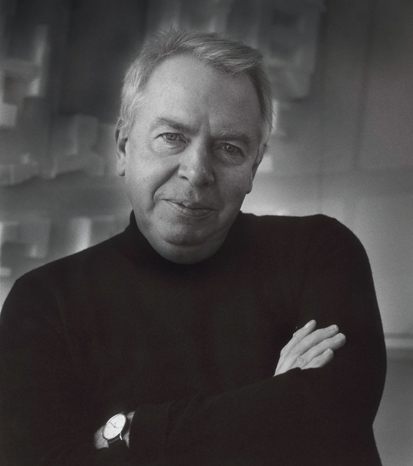

A reticent, retiring man, Forsyth doesn’t do many interviews, but to promote this new DVD he’s agreed to meet amid the serene splendour of Edinburgh’s Museum of Modern Art. ‘The kids in the film are over 50 years old now,’ he says, over coffee in a quiet corner of the museum’s cosy café. ‘Why am I still being asked to stand up and yak about it?’ Because it’s brilliant, that’s why. But you can tell he’s tired of talking about it, so I start by asking him about his childhood. Maybe that’s the best way in. A slight and wiry man with a thinning mop of lank grey hair, he looks older than his 67 years, but when he starts talking he seems younger. As he recalls the Glasgow of his youth, his weathered face softens, his voice lightens, and the past few decades melt away.

He was born in 1946, near the shipyard where his father worked. ‘I grew up very close to the river.’ Sitting at his desk at school, he could hear the shipbuilders on the Clyde. He was the youngest of three children, with two older sisters. ‘There weren’t too many books in the house,’ he recalls, but he liked novels more than movies: The History of Mr Polly; The Catcher in the Rye… He wanted to become a writer, but when he left school, in 1964, he answered an advert in the local paper: lad required for film company. ‘It was basically a one man and a boy outfit.’ His boss made short sponsored films, which he edited in his home cutting room. ‘I had to do virtually everything he didn’t,’ says Forsyth. ‘I had to learn how to run the projector and splice the shots together.’ Forsyth learned to do all sorts of cinematic odd-jobs (‘assistant editor, assistant cameraman, assistant sound recordist…’) and eventually set up on his own, with two pals — a writer and a cameraman. They made public-information films, Highland travelogues… It was the perfect apprenticeship. Finally, after 15 years of film-making, he wrote an outline for a feature film, about a shy Scots lad who falls for the female striker in his school football team.

Forsyth went to the local youth theatre to find some actors for his movie, but the British Film Institute declined to fund it (they said it was too commercial) so Gregory’s Girl hit the buffers. However, by now he’d become good friends with these youthful amateurs, so he went ahead with a (much) cheaper film, about some unemployed youngsters who steal a lorry-load of kitchen sinks. For Forsyth, this was his last shot. He’d wound up his production company. His car was up on bricks. ‘If we hadn’t made a go of it, my plan was just to disappear.’ Success came just in time. That Sinking Feeling was the surprise hit of the 1979 Edinburgh Film Festival. Now he could raise the money to make Gregory’s Girl, with many members of the same cast.

That Sinking Feeling cost a few thousand pounds — a record low for a full-length feature (ironically, it’s just been rereleased on DVD by the BFI, whose refusal to fund Gregory’s Girl led to the making of that shoestring movie). Gregory’s Girl cost a few hundred thousand, but it still felt just as fresh. The magic ingredient was Forsyth’s relationship with his young cast, resulting in performances of unique candour. ‘They knew me well enough, and I knew them well enough, to find a way of telling them what I wanted,’ he says. ‘Their energy and their enthusiasm was what carried it.’

Another key factor was the location. Forsyth shot That Sinking Feeling in the run-down East End of Glasgow. For Gregory’s Girl, he chose a very different setting — the Scottish new town of Cumbernauld. ‘This film is about youth,’ he thought. ‘Why don’t we set it in a brand-new place?’ This decision was a masterstroke. The bland neutrality of Cumbernauld freed his characters from their surroundings, and gave his simple story broad appeal. It even got a US release, albeit with diluted Scots accents (the ‘Edinburgh version’, as Forsyth calls it) and made stars of John Gordon Sinclair and his raw co-star, Clare Grogan. Forsyth met her in a Glasgow restaurant, where she was working as a waitress, and cast her as his romantic lead. He had a good nose for star quality. Between the shoot and the first screening, she also became a pop star, adding a dash of glamour to this Strathclyde fairy tale.

Gregory’s Girl won a Bafta for Best Screenplay, and led to Forsyth’s crowning glory, Local Hero. This modern fable won him another Bafta, this time for Best Director. His next movie, Comfort and Joy (a romantic comedy set against the backdrop of Glasgow’s ice-cream wars), was his masterpiece, but after that his career seemed to take a series of increasingly strange turns. Housekeeping was a fine film, and a critical success, but this adaptation of an American novel seemed like an odd choice for someone with such a natural feel for his native Scotland. ‘I just made that film because I’d read the book and had fallen for the book,’ he says, simply. He then directed Breaking In, a crime caper with Burt Reynolds, and wrote and directed Being Human, a time-shift epic with Robin Williams. That ill-fated film was the end of his Hollywood career — so far.

Forsyth’s last film, 15 years ago, was Gregory’s 2 Girls, which finds John Gordon Sinclair’s Gregory back at his old school as an English teacher, lusting after one of his female pupils. It wasn’t as bad as it sounds, but making a grown-up sequel to his teenage classic felt almost sacrilegious. ‘People have enshrined it in such a personal way. I was tampering with something I didn’t have a right to tamper with.’ It got ‘mixed’ (i.e., mainly bad) reviews but he doesn’t sound too bothered. ‘It didn’t do any business at all,’ he says, cheerfully. ‘It satisfied me but I don’t know if it satisfied anyone else.’

He hasn’t made a film since, and he doesn’t seem to miss it much. ‘Every film is tough. There’s actually very little fun in making films, as far as I can find out.’ He has two grown-up children. You can sense he has a life elsewhere. It seems bizarre that a filmmaker with such perfect pitch should be so happy to walk away, but if there’s a hidden reason for this riddle then Forsyth isn’t telling. ‘I just sit at home and I think up things to write, and then sometimes there’s enough ideas to put into the shape of a film, and then I go out and find someone to make it. I’m like a shoemaker. If there’s shoes to make this week, then I’ll make a pair of shoes. I don’t actually feel like I belong to an industry. I don’t feel that I’m part of the British film industry, the global film industry. I don’t really feel that way at all.’

Of course it’s perplexing that Forsyth should make four wonderful films in five years and hardly anything in the next 30, but the creative peak of many careers is often extremely brief. ‘I feel like a bit of a fossil,’ he says, but who cares if he hasn’t had a hit for a quarter of a century? He made four great movies, and that’s four more than most film-makers ever make. The museum is closing. We catch the last bus back into town. We get out and say goodbye and then he disappears into the rush-hour crowd.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Gregory’s Girl, Second Sight, £15.99; That Sinking Feeling, BFI Flipside, £19.99.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in