I met George Macdonald Fraser when he was the features editor of the Glasgow Herald. He was a very good newspaperman on what was a fine daily paper. James Holburn was the editor, Reggie Byers his deputy, Chris Small the literary editor, all admirable and amiable journalists. When Holburn retired, Fraser was for a while acting editor and should have been made editor and would have been fair and fearless. Had he tired of the daily grind he might have become cantankerous; but his devoted readers and Hollywood would only have had to wait another 20 years for the flowering of his prodigious talents.

When I left the Glasgow Herald, I spent three years on the Scotsman doing the book pages and then became an editor at an embryo publishing conglomerate within which was the house of Herbert Jenkins, publisher most famously of P.G.Wodehouse. The first volume of The Flashman Papers came in the following year, 1968. It was read initially by the music editor, David Sharp, and then by everyone in the office, including Leopold Ullstein, the publisher, who loved it, and by his Russian wife, who didn’t understand a word of it.

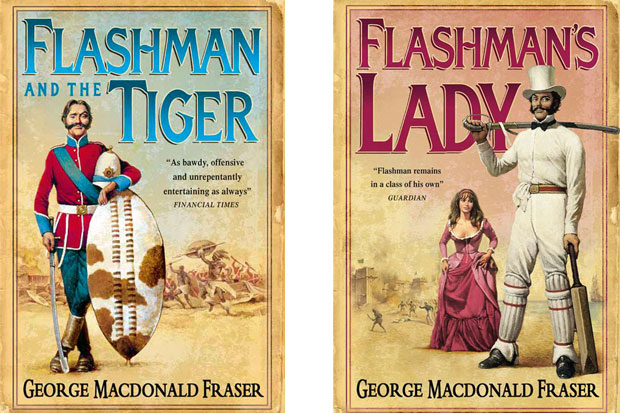

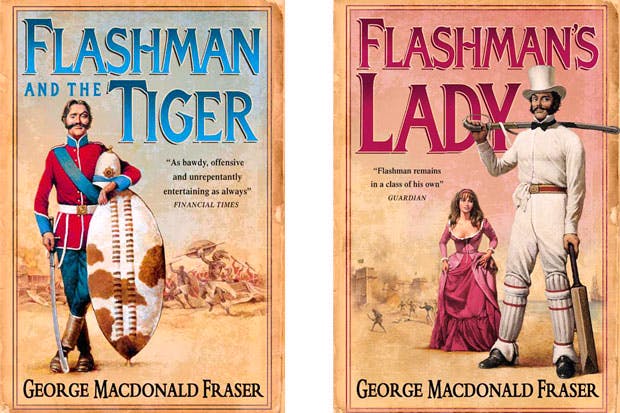

The immediate success of the book owed something to the inspired choice of Arthur Barbosa to design the cover. He was chosen by Richard Wadleigh, the production director, because for years he had made beautiful jackets for the novels of Georgette Heyer. George was delighted by all the paintings Barbosa made for his books, though there may have been one — for Flashman and the Redskins — that was adjudged unbecoming.

Flashman was launched in Edinburgh, of all places. The Ullsteins came from London; the American publisher, Sidney Kramer, and his wife came from New York. In the course of dinner at Prestonfield House, punctuated by the shrieks of peacocks, it began to dawn on Kramer that it was a novel that he had acquired. Yet he never wavered.

That colourful evening may have been only a short time before the Frasers went to the Isle of Man for a weekend to reconnoitre a possible future home. They never did come back, or saw their Glasgow home again until years later (I was with George at the time, and he evidenced a minimum of nostalgia). They lived near Douglas, in glorious and studious isolation, to the ends of their lives. Every tea break resembled a leader-writers’ conference, with Kathy giving as good as she got, as wise and as well-read as her husband.

George somewhere makes the woeful claim that he had never been a bestseller. He certainly was when Flashman was published. It was a straightforward matter to arrange it in those days: four copies of the book would be bought in Foyles, four in Hatchards and four in Dillons. The final Flashman novel was vigorously published by Susan Watt at HarperCollins and was also, as gave the author great pleasure, crowned a bestseller.

Most evidently the Flashman novels were not to everyone’s taste. I know of only eight women in 45 years who professed to have been seduced by them. My father, once a publisher and subsequently a vicar, read a very few pages of the first novel and said: ‘Take it to Handyside Buchanan of Heywood Hill. He was my contemporary at Rugby. He may find it comical.’ He didn’t, in fact, but he in turn said: ‘There is a young man downstairs [John Saumarez Smith], who positively enjoyed the book. I shall not stop him selling it.’ Nor did he, and Heywood Hill’s loyalty to Fraser has never failed.

George filled his days with work and with reading. I was happy to discover that the research for The Steel Bonnets: The Story of the Anglo-Scottish Border Reivers, was done together with Kathy in libraries in Dublin. It too has a cover by Barbosa and the two reivers pictured on it are portraits of Jack Charlton and Nobby Stiles — a homage typical of Fraser. The book is masterful history, a thorough account of the enmities and skirmishes and battles between 80 distinct families (including Kathy’s forebears, the Hetheringtons, described as blackmailers and murderers). The narrative, over a broad geographical and historical span — more than 300 years — is utterly beguiling. George could not accompany the photographer Alexandra Lawrence throughout the Borders, but he himself supervised the journey from afar and all but drew the superb maps made by William Bromage.

The last book of George’s I published was The Hollywood History of the World. It is an authoritative and extravagantly illustrated work, which explores in a way both personal and critical a subject that was close to his heart. I seldom heard about how exasperating it was to work in Hollywood, with all its manias and egomaniacs and the burden of being away from home; and I will never forget the joyful accounts of his dealings with Steve McQueen — who once read a page of George’s dialogue and said he would sooner act it than say it, and proceeded to do so, shifting an eyebrow, a nostril, a lip … and the work was brilliantly accomplished. Or tales of dinner with Burt Lancaster and Oliver Reed. George, with his encyclopaedic knowledge of the film industry, must have been a pure delight for all of them too.

His best book is Quartered Safe out Here, which I have often heard described as the finest military memoir ever written. It is the exceptionally modest story of Private Fraser’s war against the Japanese, published almost 50 years after the events it describes. The blurb for the first edition reads:

After 25 years of chronicling the military misadventures of Flashman, the Victorian arch-cad, George MacDonald Fraser has temporarily deserted fiction to write his own factual and highly personal account of the Burma War. Quartered Safe out Here describes life and death in Nine Section, a small group of hard-bitten and (to modern eyes) possibly eccentric Cumbrian borderers with whom the author, then 19, served in the second world war, when the 17th Black Cat Division captured a vital strongpoint deep in Japanese territory, held it against counter-attack and spearheaded the final assault in which the Japanese armies were, in General Slim’s words, ‘torn apart’. It is very much a private’s-eye-view of a strange, almost guerrilla-like war; as a description of the Fourteenth Army infantryman’s lot — night attacks, ambushes, patrols, close encounters with a fanatical enemy, and set-piece battles, and of the thoughts, words, and deeds of the men themselves — it is unusual, and possibly unique. It is war in close-up: fearsome, sometimes appalling, often funny, and always a disturbing reminder of how the world and its attitudes to soldiers and soldiering have changed in 50 years.

You will recognise the hand.

George supposes in one of his memoirs that he must have been a nightmare for an editor. He wasn’t. You just knew where you stood. If you queried the spelling of a word he would say: ‘And what dictionary are you using?’ I would say: ‘Chambers.’ And he would say, ‘Well, I’m not!’ His American publisher asked him to remove the n-word from Flash for Freedom, the story of the slave trade and the undergound railroad. All he said was: ‘Would you have dared to say as much to Mark Twain? Send back my contract.’ In the event not a voice was raised in protest.

As features editor on the Glasgow Herald he did not hesitate to slash your copy to ribbons; as an author he turned in flawless prose, wrote the blurbs and never made a mistake, save possibly one. He misspelled an ancient aunt of his paperback publisher, Clarence Paget, who was involved somehow in the retreat from Kabul. The happiest mistake he didn’t make was to have remembered, at the end of Flashman at the Charge, that Flashman — having been rescued from the brink of execution in Lucknow by a British officer — should be brought the news that a book had just been published in London entitled Tom Brown’s Schooldays.

I think the only thing I did for him that he could not have done for himself was to have persuaded P.G.Wodehouse to read his work. And the latter wrote: ‘If ever there was a time when I felt that watcher-of-the-skies-when-a-new-planet stuff, it was when I read the first Flashman.’ A whole new planet indeed.

Finally, perhaps not well enough known, a snippet of autobiography, from his introduction to a new edition, 20 years ago now, of Treasure Island:

Sixty years ago the superintendent of Carlisle swimming baths decreed that no boy of 12 years or under should use the high diving board. R.L. Stevenson was to blame for this, and would no doubt have been gratified, if not at the prohibition, at least at the reason for it. The film version of Treasure Island, with the immortal Wallace Beery as Long John Silver, was showing at a local cinema, and no incident in that splendid production had so excited our juvenile admiration as the moment when Israel Hands, played by that matchless villain, Douglas Dumbrille, dragged his way up the shrouds of the good ship Hispaniola, dirk in teeth, in pursuit of Jim Hawkins, only to be properly shot and make his fatal, twisting plunge into the watery depths. It cried out for emulation, and the deep end of the baths was rendered perilous by a constant swarm of urchins struggling to the high board and toppling backwards with realistic death-screams, regardless of the orthodox bathers below. Hence the ban. But that is Fame, and Stevenson would have been the first to recognise it.

The post The road to bestsellerdom appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in