Earlier this year, I sat down and watched Kenneth Clark’s groundbreaking TV series Civilisation. I vaguely remember when it was first screened in 1969, but was too young to appreciate it properly. This time around it made splendid Sunday afternoon viewing: Clark’s distinctive blend of authority and humour, his ability to convey information and enthusiasm without the slightest trace of condescension, coupled with effective camerawork and good editing, make a rich and stimulating brew of word, image and music. The series, which was commissioned by David Attenborough and brilliantly directed by Michael Gill, established a model for all subsequent arts documentaries. Not only did I learn a lot from its 13 episodes, I also enjoyed it enormously as entertainment. I’ve a feeling it won’t be long before I give it another airing…

Kenneth Clark (1903–83) was a remarkable man: scholar and collector, arts administrator and public servant, the youngest ever director of the National Gallery (1934–45), and in the 1950s, as chairman of the Independent Broadcasting Authority, he oversaw the creation of ITV. (Well, he couldn’t get everything right.) He was the single most influential figure in 20th-century British art — as patron, collector, broadcaster and writer, arbiter of taste and impresario. He was a great and genuine populariser and it is wholly fitting that the Tate should now honour him in a large exhibition of nearly 300 works, many of which at one time he owned. Actually, there is so much top-quality work to see in the Clark show at Millbank that the visitor should allow plenty of time for leisurely looking, or be prepared for a return visit.

The exhibition starts with the famous 1963–4 portrait of Clark by Graham Sutherland, together with some earlier portraits of the great man (by John Lavery and Charles Sims) and some of the art Clark grew up with (Landseer, Japanese prints, and that underrated draughtsman Charles Keene). There are marvels in this first room: a little Giovanni Bellini of the Virgin and Child from c.1470 (now in the Ashmolean), Constable’s full-size sketch for ‘Hadleigh Castle’ (now in the Tate), Samuel Palmer’s magnificent ‘Cornfield by Moonlight with the Evening Star’, which was so influential on the neoromantics. Also here is a deluge drawing by Leonardo da Vinci and two drawings of nudes, one identified by Clark as authentic Leonardo (on whom he wrote a scholarly but accessible book) and the other by a follower.

Room 2 contains even more extraordinary things, chief among them two important paintings by Seurat (I especially liked his Corot-ish trees), and various beautiful things by Cézanne. Clark owned six oils by Cézanne, of which three are in this show, one of them, a small study of bathers, glowing here between a terracotta head of Renoir by Maillol and a marvellous maiolica relief by Luca della Robbia. Clark had deep pockets and a real passion for collecting, buying works from all ages, from Sèvres porcelain to Egyptian antiquities, relishing the visual spark created by unexpected juxtapositions of periods and styles. In 1933 he bought about 50 drawings and watercolours by Cézanne, several of which are also on display, reassuring a friend that they cost ‘much less than a modest motor car’. There seems to have been no end to his collecting: he owned at least ten small Constables, several paintings and drawings by Matisse and a major 1913 collage by Juan Gris. In the early 1950s he bought Turner’s ‘Seascape: Folkestone’, identified by the Tate’s Chris Stephens as probably the most important painting Clark owned.

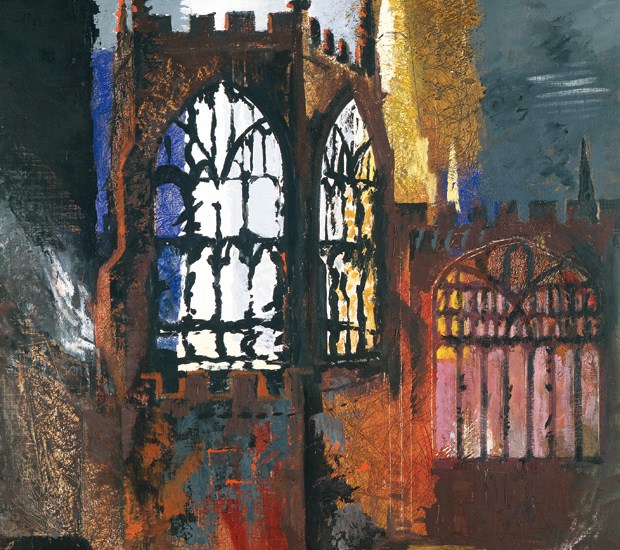

There’s not enough space in this column to comment on the many glories of the exhibition, so I’ll simply mention some of the highlights. Clark supported the Cézannesque Euston Road School and bought good paintings by William Coldstream as well as Victor Pasmore, but the revelation here is the work of the rarely seen Graham Bell, who died tragically young when his Wellington bomber crashed during a training flight. Note particularly his atmospheric little painting of Brunswick Square and the larger Cézanne tribute ‘Mont St Victoire’. Henry Moore comes out well, but it’s revealing that Clark never bought a large sculpture by him (too abstract, perhaps?), seemingly preferring the more humanist shelter drawings. Piper and Sutherland are well served and Paul Nash dominates the wartime Room 5 with his vast but oddly lyrical ‘Battle of Britain’ canvas.

Clark had no problem with asserting his own ideas. As he said: ‘The ideal patron doesn’t simply pay an artist for his work. He is a man with enough critical understanding to see the direction in which the artist ought to go.’ Thus in letters he tried to put Sutherland off the Surrealists or direct what Victor Pasmore might do next. Pasmore must have been a great disappointment to him, for Clark had little time for abstraction and Pasmore famously converted to non-figurative art in 1948. Prior to that he painted Turner-ish, sub-Whistlerian landscapes, and wonderfully corporeal nudes — partly in response to Clark’s prized possession, Renoir’s great painting ‘La Baigneuse Blonde’ (1882), which is sadly not included in this show. Clark helped both Pasmore and Sutherland to buy houses, bought and promoted their work, and enabled them to be full-time artists. But there are no later Pasmores here, none of his gloriously inventive abstract paintings or constructions, and only one abstraction by Ben Nicholson, a white relief which is not among his finest works.

I went to the show twice in a week, and between visits read the catalogue (£24.99 in paperback). I found this fascinating, though it is one of those publications that can’t quite decide whether it is an exhibition catalogue or a stand-alone book, and so falls uneasily between categories. For instance, it contains a numbered list of the works in the exhibition, but the exhibits themselves are not numbered in the gallery, so cross-referencing is difficult. Usefully wide-ranging essays cover such aspects of Clark’s career as his roles as patron and collector, his home at Saltwood Castle, his TV performances and his crucial position as chairman of the War Artists Advisory Committee. Yet the writing doesn’t sufficiently relate to the exhibition. The biggest puzzle when going round the show is which pieces Clark actually owned and which he simply facilitated into public collections. I overheard visitors asking each other this question and was even asked it myself. The individual status of exhibits is far from clear.

But the best thing about my second visit was finding that the exquisitely beautiful Francisco de Zurbarán still-life that Clark did once own, but which now resides in the National Gallery, had appeared in the last room. I hadn’t overlooked it — it had been away on loan to a big Zurbarán exhibition in Brussels, and was only hung on 28 May, over a week after the Tate show opened. So if you went before then, here’s a good excuse for going back: it’s such a fabulous painting and it’s good to be reminded how fine Clark’s eye really was. Now the show ends even more powerfully, with Zurbarán joining a Tang dynasty lion, Cézanne’s ‘Le Château Noir’ and Henry Moore’s 1932 ‘Composition’ carved from dark African wood, sparely placed in the final gallery. I left uplifted and wanting to go back.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in