The Welsh Marches, gloriously unvisited amid their wooded hills and swift-flowing streams, have remained mysteriously off-limits to the sort of novelist eager for territorial rights to a particular landscape or locality. Apart from Bruce Chatwin’s On the Black Hill and Mary Webb’s torrid 1920s sagas of heartache and claustrophobia in field and farmhouse, fiction has mostly steered clear of Wye, Teme and Clun and their adjacent mountains.

Along comes Laura Beatty, however, not to trouble this haunting remoteness but to use it, with subtle obliquity, as a grid for mapping the emotional lives of her twin heroines, women divided by nearly four centuries. Each is an incomer to the Marches, brought there by force of circumstance and, in one case, longing to get away but destined never to leave. A major element of Darkling’s subdued potency is the idea, intimated rather than flagged up, of this rural scene as simultaneously nurturing and pitiless in its serene continuity.

Modern Mia Morgan, mourning a dead lover, is researching the 17th-century gentlewoman Brilliana Harley, heroic defender of a Herefordshire castle during the civil war and hailed by contemporaries as ‘this honourable lady of whom the world was not worthy’. Mia’s career, less turbulent and scarcely as colourful as Brilliana’s, balances a brittle, semi-detached London life with visits to her blind father John, a Scottish farmer who has fetched up in a village west of Ludlow, tended by his self-denying sister-in-law Ines.

The prevailing reticence among these three adds its own contrapuntal strand to a novel in which texture matters far more than plot. When Mia becomes pregnant following a night with Felipe, vagabond cousin of her best friend Syl, she volunteers the information to John and Ines while answering a phone call to someone else. John ripostes with the announcement that she too was conceived out of wedlock and her aunt, jolted into angry recollection of the family’s disapproval, grows defiantly tearful. But only for a moment, this is the point. About them all hangs a laconic toughness which the Marcher landscape, with its ruined fortresses and wheeling buzzards, seems to engender.

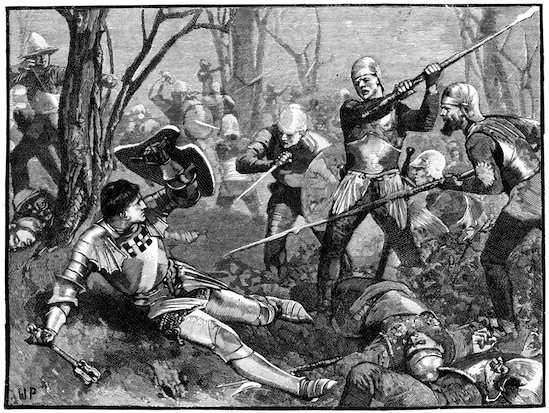

A similar resilience has been acquired, faute de mieux, by Brilliana Harley, parked in Herefordshire by her ambitious husband to raise their children while he wields power and influence in London as Charles I’s Master of the Mint. With the outbreak of war she has to make Brampton Bryan Castle ready for a siege by brutish, vain-glorious Royalists, to whom the Harleys’ fervently-espoused puritanism is a grotesque anathema. ‘Fear curdles in her chamber in the moments she is alone, to put its cold hand at her neck.’ Brilliana nevertheless triumphantly sees off the King’s army, ‘with the law of nature, of reason and the land on my side and you none to take it from me’.

Beatty, here as elsewhere in the book, uses Lady Harley’s own words, as well as her spectacularly approximate spelling, to further enrich that complex stylistic web which forms the book’s chief pleasure. Preparing for a second siege, with the castle half ruined and its surrounding village reduced to ashes, Brilliana dies of sheer exhaustion. Mia, her baby growing within,walking up ‘the wind-backed hills’, looking for Brilliana amid a modern culture of ‘trash and compromise’, finds an image of endurance in this rain-sodden Marcher landscape. This ultimate spiritual confrontation between the two women provides an exhilarating coda to a novel of masterly understatement.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £14.99. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in