A couple of years ago in Jamaica, I met Errol Flynn’s former wife, the screen actress Patrice Wymore. Reportedly a difficult and withdrawn woman, her life in the Caribbean (apart from the few details she cared to volunteer) could only be guessed at. The Errol Flynn estate, an expanse of ranchland outside Port Antonio, was grazed by tired-looking cattle. ‘Haven’t we met before?’ Wymore said to me as I walked into her office after knocking. ‘You remind me of someone I know.’

I took in the riding crops and spurs hanging on the wall. After eight years of marriage, in 1958 Wymore had divorced Flynn, who died the following year at the age of 50 having more or less boozed himself into the grave. Flynn had been quick to discover Port Antonio, a drowsy United Fruit company banana port; in 1946 he brought himself a gingerbread mansion there and launched the tourists’ pastime of river-rafting in the Caribbean. By the time Wymore starred with Flynn in the movie King’s Rhapsody (1955), his sexual philandering and drinking had become so bad that he had to play sexually philandering drunks. On Flynn’s death, Wymore inherited 800 head of Jamaican cattle from him. She did not seem to know what to do with them.

Only tourists think of the Caribbean as a ‘paradise’, Wymore told me. Each day the planes land, the cruise ships call, and the tourists arrive for their dream holiday in a region where you can pass from enclaves of immense wealth to utter desolation in a matter of seconds. Jet-setters and other plush folk in search of sex and rum-fuelled oblivion typically sugar-coat themselves against the poverty behind the walls of their all-inclusive resort hotel, where they can get married in the nude on the beach, or dress up as Errol Flynn in Captain Blood and whoop it up on a motorised pirate galleon. Wymore herself has had to contend with allegations that Flynn enjoyed sex with Jamaican boys. ‘Errol, gay? Don’t you think that I would have noticed?’

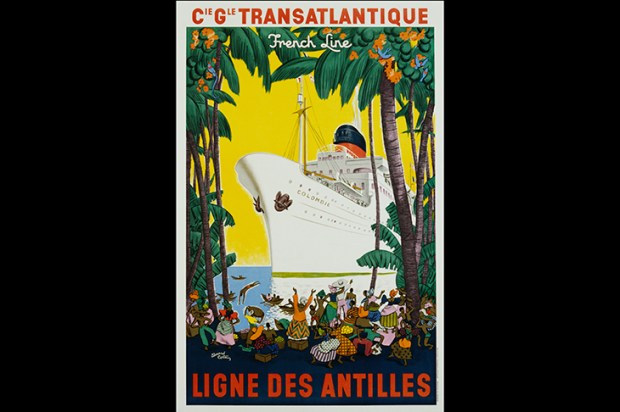

Carrie Gibson, in her epic history of the Caribbean, Empire’s Crossroads, casts a sombre eye on the effects of tourism. Even more so than the narcotics trade, tourism has transformed the face of the West Indies. Once, not long ago, Jamaica was an island frequented by a handful of well-heeled voluptuaries like Flynn. However, the advent of the long-haul charter flight, Apex-fare tariffs and packaged hedonism brought with it a mass of disfiguring breeze-block resorts, shopping arcades and sport-cabin villas. A sense of how it must have been to see the Caribbean for the first time — the semi-tropic greens and blues and the shallows where the slave ships anchored — is hard to imagine.

Slavery is, inevitably, central to Gibson’s account of the sugar islands. During the period 1700 to 1808, sugar — the end-product of British slavery — became so profitable a commodity that the prosperity of English slave ports such as Bristol and Liverpool was derived from commerce in what the historian Sidney Mintz has called the ‘tropical drug food’.

Gibson, a former Guardian journalist, sees the Caribbean as a ‘crossroads’ for people, commerce, plants, animals and disease. Contract labourers from India and China married into the slave populations during the 19th century, creating a multi-shaded community of nations which was in some ways oddly modern. Caribbean countries are not uniformly black; many gradations — Chinese, Indian, Lebanese — can exist within a single Cuban, Martinican or Haitian family. From Columbus’s landfall in San Salvador (Bahamas) in 1492 to the Black Power independence movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the Caribbean as we know it today was the ‘product of an encounter between Europeans and other people’, writes Gibson.

Gibson’s is an ambitious undertaking. Apart from the accident of their having been under British rule, Barbadians, St Lucians, Guayanese and Jamaicans have very little in common with each other. Were you to superimpose a map of Europe on the Caribbean, Jamaica would be Edinburgh; Trinidad, north Africa; and Barbados, Italy: the islands are that far apart.

How to compress their histories into a book such as this for the interested layman? Gibson tells the common story of how discovery by Columbus ushered in African slavery and, five centuries later, the American influence so prevalent today. She depicts the influence as largely injurious. Conceivably Jamaica lost something after independence from Britain in 1962, when the United States — the ‘Colossus of the North’ — began to strengthen its presence, and the Caribbean island which had been overrun by one kind of empire was overrun (in a different way) by another. Anthony Trollope, during his 1859 tour of the Caribbean, accurately predicted that England would one day be ‘no more than a name’ in the West Indies.

Empire’s Crossroads is not without its clichés (‘motley crew’, ‘heated debates’), yet it remains a vivid and thought-provoking work of historical synthesis, with excellent chapters on the Haitian slave revolt under Toussaint L’Ouverture and the anti-colonial Morant Bay uprising in Jamaica in 1865. As for Errol Flynn’s long-suffering wife Patrice, she died in Jamaica last March, at the age of 87, having seen all she wanted to see of paradise.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £21.50. Tel: 08430 600033. Ian Thomson is the author of The Dead Yard: A Story of Modern Jamaica and Bonjour Blanc: a Journey through Haiti.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in