The Hallelujah Chorus crops up in the most unexpected places, says Michael Marissen in his new book about Handel’s Messiah. For example, it’s used in a TV ad ‘depicting frantic bears’ ecstatic relief in chancing upon Charmin toilet paper in the woods’.

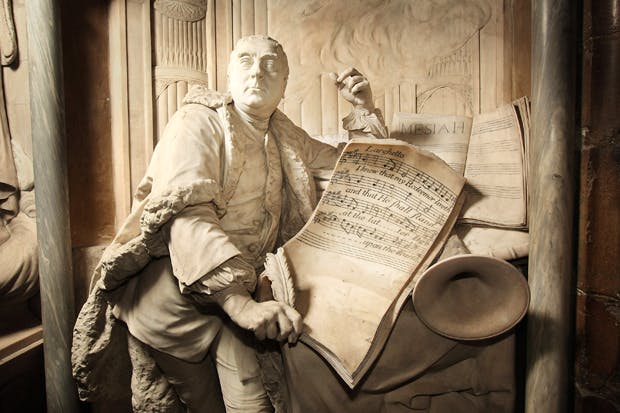

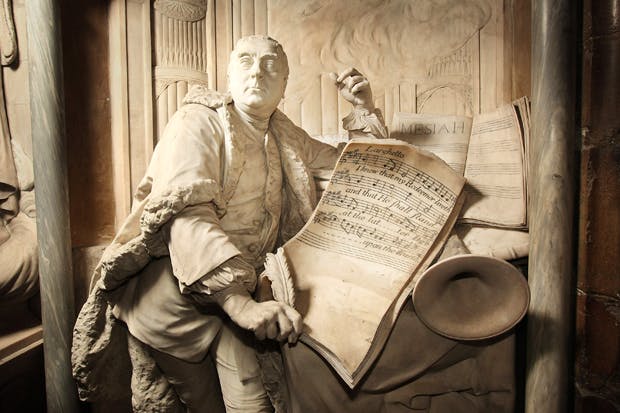

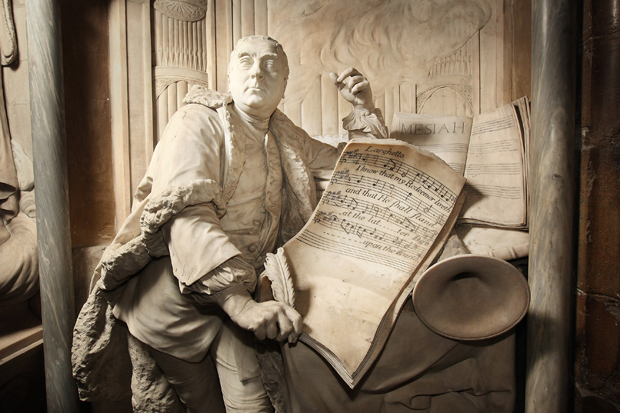

That’s an amusing detail: it lingers in the mind. But, as you can work out from the title, Tainted Glory in Handel’s Messiah isn’t intended to be a fun read. Marissen, an American specialist in baroque music, has been taking a long, hard look at the oratorio’s libretto, adapted from the Old and New Testaments by Charles Jennens, a gentleman scholar. He has uncovered a disturbing subtext — ‘hateful sentiments’ directed against Jews that are masked by the magnificence of the score. And he thinks this should make Christian audiences (his own background is Dutch Calvinist) feel uncomfortable.

Let me try to sum up his argument. Messiah famously leaps between the Gospels and the Hebrew Bible, as we are now supposed to call the Old Testament. Consider its first words: the recitative ‘Comfort ye’ leading into the aria ‘Ev’ry Valley Shall Be Exalted’, exquisitely decorated by the tenor Charles Daniels in McCreesh’s recording with the Gabrieli Consort. The words are from Isaiah 40:

Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, said your God; speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her Warfare is accomplished, that her Iniquity is pardon’d.

For Jews, ‘ye my people’ refers to the prophets or perhaps the priests of Israel. For Jennens, and indeed for most 18th-century Protestants, the verse was addressed prophetically to Christians who have accepted Jesus as the Messiah, who forgives them their iniquity. The book lists many examples of such impertinence. The choir sings ‘And He shall purify the Sons of Levi’ (Malachi 3:3). That sounds innocuous enough, but Marissen suspects that Messiah is referring to the ‘purification’ (i.e., destruction) of the Temple by the Romans in AD 70: a vengeance visited on the Jews by Jesus for their failure to acknowledge Him. And perhaps it also signals the end of the ‘impure’ carnal sacrifices of the Temple.

Then consider the words from Psalm 2, ‘Why do the nations so furiously rage together…?’, roared out by the bass soloist above wildly surging strings. Most old versions of the Bible use the word ‘heathen’ rather than ‘nations’. Marissen reckons that ‘heathen’ is easier to sing — so why did Jennens choose an alternative translation? Perhaps because ‘nations’ can be made to conjure up quarrelling Jews (who were never considered to be heathens).

This is where my patience ran out. Marissen sounds like one of those bogus archaeologists determined to find evidence of the Mayan script on the Rosetta Stone. As it happens, ‘nations’ is easier to sing than ‘heathen’ — try it — and less likely to be misheard by the audience. Surely that’s why Jennens and Handel chose the word. This isn’t to say that Marissen’s thesis is entirely wrong: the Christian habit of scouring the Hebrew scriptures for prophecies of Jesus does offend devout Jews, particularly if it violates the plain meaning of the text. However, they’re even more offended by what they regard as the blasphemous claim that Jesus of Nazareth was God, which remains at the heart of the Christian faith. Pope Francis and Archbishop Welby may not approve of the casual juxtaposition of Old and New Testaments in Messiah, but they would never question the divinity of Christ. And every time they say the Creed they affirm that the Hebrew Bible predicts the Resurrection — ‘He rose again, according to the scriptures’.

Messiah isn’t an attack on Jews. You can make a case that its theology reflects what Marissen calls ‘anti-Judaism’, but doing so requires a lot of homework. In this respect it resembles Wagner’s operas: the composer was a venomous Jew-hater, but nobody who wasn’t aware of this would guess it from listening to his work. If you’re looking for anti-Semitism in a masterpiece I’d suggest Bach’s St John Passion, whose electrifying choruses portray Jews baying for Jesus’s blood. Unlike Messiah, those passages send a chill down the spine. But we can’t really blame Bach, since the libretto is lifted straight from the Gospel.

To sum up: Christians can enjoy Handel’s oratorio with a clear conscience, though if I were a religious Jew I might find it off-putting. End of story. Incidentally, I’m not sure Marissen is right about the advert with the bears, the loo paper and the Hallelujah Chorus. I can’t find any trace of it on the internet. Although Charmin does make ads featuring cartoon bears, none of them includes a note of Handel. Instead, the creatures discuss the special absorbency of the tissue, which means you need fewer sheets than usual. They go into a surprising amount of detail, but I’ll spare you that.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in